RECKONING DAY

RECKONING DAY

RACE, PLACE, AND THE ATOM BOMB IN POSTWAR AMERICA

Jacqueline Foertsch

Vanderbilt University Press

NASHVILLE

2013 by Vanderbilt University Press

Nashville, Tennessee 37235

All rights reserved

First printing 2013

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

LC control number 2012035734

LC classification number E185.61.F64 2012

Dewey class number 323.1196073dc23

ISBN 978-0-8265-1926-9 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-8265-1927-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-8265-1928-3 (ebook)

from Tomorrow! by Philip Wylie.

University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Long ago, as the story often goes, this book was born through the reading of key texts with a group of engaged and intelligent students. In the case of Reckoning Day, the texts were authored by Pat Frank, Judith Merril, and Philip Wylie, all of whom play featured roles in this books second chapter, and the students were members of my Cold War Literature and Culture class at the University of North Texas. While my debt to these authors and the many others joining this conversation is, I hope, implicit in each word that follows, this is the place to thank those smart students and the ones who have learned alongside me in succeeding semesters at UNT; their interest in our shared subjects and love of literature of all kinds inspire me daily.

I thank as well the terrific faculty and staff at UNTthe English Departments American Studies Colloquium, whose great speakers and panels are a constant source of intellectual stimulation; Chair of English David Holdeman, whose support and encouragement means so much; Diana Holt and Andrew Tolle in the English office, who expertly assisted in the provision of essential research and travel support; Kevin Yanowski, also in the office, for serving as my de facto research assistant numberless times; Learning Technologies adjunct faculty member Jonathan Gratch for his valuable technical guidance; and the Circulation and Interlibrary Loan staffs at Willis Library, who have quite simply never let me down. This book was also vitally supported through several Small Grants and two Research and Creativity Enhancement Grants, sponsored by UNTs Office of Research and Economic Development.

Further afield, I send my thanks to the talented staffs at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building at the New York Public Library, the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at NYU, the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, and the University of Texass Perry-Castaeda Library and Harry Ransom Center. Thanks also to Martha Campbell in Austin, and special thanks to the late Paul Boyer, who encouraged and inspired me for many years. Special thanks also to Russell Wyland and my helpful readers at the National Endowment for the Humanities, who awarded this project a Summer Stipend in 2010. I am grateful as well to the readers and editors at the Journal of Modern Literature, Philological Quarterly, and Modern Language Studies, which have each published excerpts of this work. Finally, I thank Eli Bortz, the editorial and production staffs, and my helpful anonymous readers at Vanderbilt University Press.

Back at home in Texas, I was encouraged constantly by dear friends and colleagues in UNT English and across campus. Special thanks to Alexander Pettit and Harry Benshoff who kindly read parts of this work; to Walton Muyumba for our long talks about African American literature and culture (and the Mingus reference essential to my conclusion); and to Deborah Needleman Armintor, Ian Finseth, Bonnie Friedman, Stephanie Hawkins, Eileen Hayes, Jennifer Jensen-Wallach, Jack Peters, Robert Upchurch, Kelly Wisecup, and Priscilla Ybarra for their marvelous friendship and ongoing interest in my work.

I thank other dear friendsKathryn Stasio at St. Leo University and Annette Trefzer at Ole Misswith whom Ive shared the academic adventure from the start, and my beloved family, for whom I write always: Mom and Dad in Chicagoland, Christine and Mike in New York, my darling Aurora and Solana, whove made me the Happiest Aunt in America since the day they were born, and the amazing Terence Donovan, who has changed my life.

RECKONING DAYIntroduction

Mapping Ground Zero in Postwar America

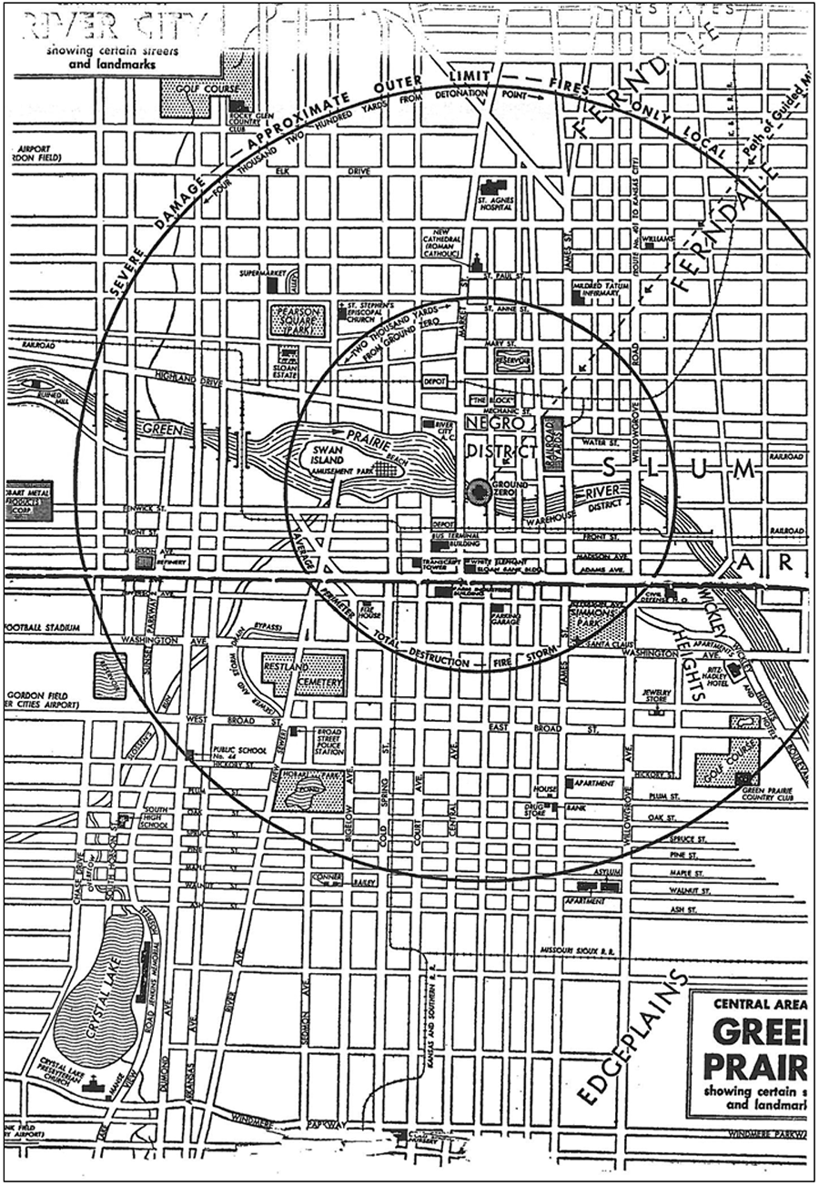

Since the genres inception in August 1945, atomic narrative has located its characters with painstaking precision with respect to the bomb. Most of the footnotes in Michihiko Hachiyas Hiroshima Diary (1955) record distances from various possible blast sites to the location of wounded friends and narrators; in Hiroshima (1946) John Hersey records the exact yardage between the point of impact and each of his interview subjects, their position behind windows, walls, or other buffers, and the life-saving (later, life-threatening) Ota River and Asano Park. Like many treating this subject, Hachiya and Hersey indicate that the worst position was not necessarily ground zero; the agonizing injuries (leading to permanent disability or eventual death) suffered by many in the mid-range between instant vaporization and the safe distance created the atomic eras first and most profound dilemma with respect to position: at this devastating moment in world history, who, and where, were the lucky ones? On the American home front, news of the two atomic flashes that ended World War II likely registered with each recipient in specific spatiotemporal detail: Where was I when I found out? What was I in the middle of? While the physical location of Hiroshimas blast victims was in every instance determinant of their survival and well-being, in America and elsewhere, the blast caused only a moment of paralysis, shortly giving way to the gyrations of victory. Yet that moment, for those still alive to remember it, remains powerfully presentlike it was yesterdayor we might say that the recollectors themselves remain trapped in that particular past. Like the shadows of figures incinerated at Hiroshimas ground zero, they remain fixed then and there in their places, transfixed by the bombs unprecedented horror and significance.

More broadly speaking, ones location in the American landscape when the bomb explodedthat is, during Americas early atomic/cold war eraintersects with ones place in the American social hierarchy in significant ways. For the bomb presented Americans, especially those who have always enjoyed more freedom of movement, with a series of spatio-ethical dilemmas: where to go if the bombs should fall, who and what to leave behind. While the suburban boom of the immediate postwar period had myriad causes, one significant reason was the strong sense that Americas cities were the easiest and most likely of nuclear targets. Elaine Tyler May has examined the leafy, low-slung, spread-out qualities of American suburbs and has persuasively observed in these a response to atomic fears of urban verticality, congestion, and entrapment. For May it was especially the hunkered down, ranch-style home that exuded this sense of isolation, privacy, and containment (94). In atomic fictions of the period, the city is depicted as the site of conflagration; those characters lucky enough to find themselves in the suburbs or on the farm on X-day fare better and depend less on which way the wind blows during the fallout period.