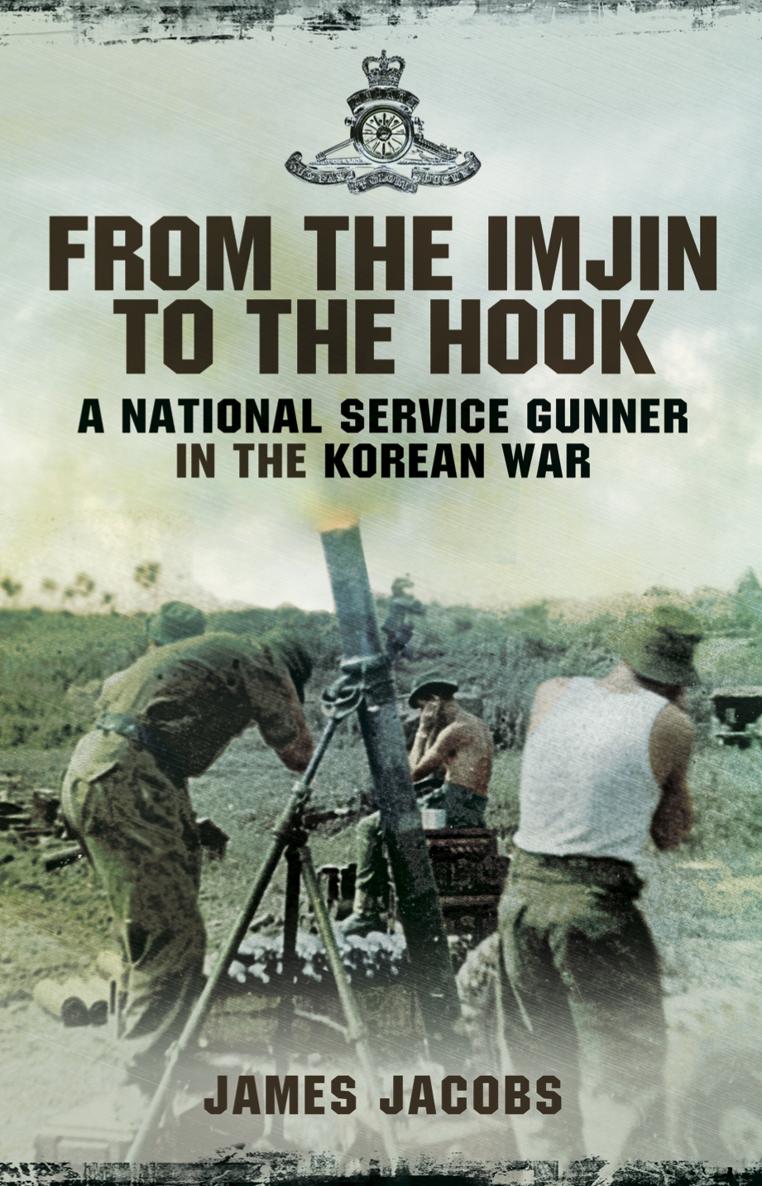

From the Imjin to the Hook

A National Service Gunner in the Korean War

James Jacobs

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jim Jacobs 2013

9781783469659

The right of Jim Jacobs to be identified as the Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Driffield, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth

Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

I f Major C.F. Lane, Battery Commander, 170 (Imjin) Battery Royal Artillery, had not invited me to attend at the Officers Mess, Woolwich Barracks, London, in October 1988 for the unveiling by General Sir Anthony Farrar-Hockley of a painting depicting 170 Independent Mortar Battery in action in Korea in April 1951, these memoirs would never have been started. Twenty-four years later, they have finally been completed.

I acknowledge the help I received from Major Lane, and also the following people, who held the positions shown in 1988: Charles Wilson of Mirror Group PLC, Lisa Wright of P&O Steam Navigation Company, Ian Mackley of the New Zealand Korean War Veterans, and Jane Carmichael, Keeper of Photographs at the Imperial War Museum, London, for whom I worked as a volunteer on the Korean War Collection in 1993, and the archivist at Gunner magazine in 1996. For those who have moved on in life, I thank you for your generous assistance, and apologize for taking so long. Photographs have been gathered from the above sources, who kindly waived copyright fees.

Over the years I have listened to the advice of fellow members of the British Korean Veterans Association, some of whom have written their own memoirs. Sadly, too many have had their last post sounded over the intervening years. Their passing has fired me with the will to write something meaningful before it is altogether too late.

I thank Brigadier (Retd) Henry Wilson, late Royal Green Jackets, Publishing Manager at Pen & Sword Books Ltd, for his insistence that I had an almost unique story that should be told and read. Without his excellent advice and encouragement this record of my military career, mostly served in the defence of another country, would not have been published. And, of course, I thank my editor, Linne Matthews, for taking me through every step along the way, and my wife Sheila, for her support and reassurance that I would, one day, have my story published.

Preface

I n times gone by, when a nation lusted after territory occupied by another, the king would mount his charger and lead his army into battle. Today, when territorial greed has reared its ugly head, or another dictator must be eliminated, wars are started by those who mostly remain remote from the danger: politicians sitting around conference tables in comfortable surroundings, who make decisions on how others will fight an armed conflict for them others who will shed blood for them, and who will die for them

Immediately prior to 25 June 1950 there would have been many such meetings north of the 38th parallel, before the army of the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) launched its overwhelming attack on the ill-prepared citizens living to the south of that artificial border. That army, the Inmin Gun, started a three-year war that was first reported as a police action.

During those three years, 81,000 personnel of the British Armed Forces were involved in the preservation of independence for the country under attack in what would become known as the Korean War, the first war in which western nations were pitted against the remorseless spread of communism throughout Asia, the only war fought under the banner of the United Nations. Today, veterans of that distant conflict refer to it as the Forgotten War, consigned as it was to virtual oblivion by politicians and people alike.

The British people had only recently experienced six years of warfare; they wanted no more. Our politicians were more concerned that the conflict would draw too many of our service personnel to Northeast Asia, when they perceived the real threat was closer to home, in Europe, with the Soviets.

So in extreme contrasts of temperature, 56,000 British soldiers played their part in vicious ground fighting during Siberian winters and oppressive summer heat and torrential rain. Approximately 25,000 men of the Royal Navy and Royal Marines patrolled the seas off the Korean coast, with a Royal Marines Commando operating on land, and a small number from the Royal Air Force maintaining air supremacy while attached mostly to United States Air Force squadrons. For weeks on end, front-line troops existed in self-dug holes in the ground and squalid trenches, the like of which had not been experienced since the First World War. They were shelled and mortared daily, and assaulted by massed, fanatical enemy infantry.

In 1950, the British Army, reduced to 420,000 following mass demobilization after the Second World War, consisted of four categories of soldiers. There were the regulars who had taken the Kings shilling many of them experienced veterans of war. Then there were the reservists who had been recalled to the colours for a fixed period to serve in the Korean War. Others were known as K volunteers, men who had left the service but had volunteered for service in Korea for a maximum of eighteen months. And there were also the conscripted youths, the National Servicemen, hastily trained in the ways of the military, and without whom Britain would have been unable to satisfy its many commitments across the world. By 1953, 70 per cent of the Army consisted of conscripts, swelling the number of soldiers to 443,000.

These personal recollections of my experiences of war in Korea are dedicated to all of my former comrades, regular, reservist, K volunteer and conscript alike, who served sovereign, country and the politicians to the very best of their ability; those who came home and those who did not. We left too many behind in the superbly maintained United Nations Cemetery at Pusan, and also those who died in prisoner of war camps in the north. There were others whose remains were never recovered, who lie forever in that far-off land, including in excess of 300 National Servicemen whose families were never thanked by the government for their sacrifice.