Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State

University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania

University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western

Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4677-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4678-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4679-9 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

I NTRODUCTION

William Kerr Scott was the most controversial, polarizing, and successful North Carolina politician of his age. When Simmons Fentress, a writer and astute observer of North Carolina politics, evaluated Scott at the end of his four-year term as governor, he referred to him as the centurys most cussed governor: Columnists and commentators attacked him as a political accident, a notorious spender of other peoples money, a dangerous liberal tied to Harry Trumans coattail, a governor of only half of the people. The man who changed the face of the state was, according to Fentress, as plain as a plow point, as candid as a school kid and as stubborn as an Alamance mule and just as unpredictable. While many would be glad to see him go, the gladdest are the men in the front offices of the big utilities. Fentress concluded that Scott would be remembered as a builder but that he was, essentially, a needler, a provoker, a builder of fires under the foot-draggers and the indolent, but always for a good cause. The governor brought a new level of political courage to Raleigh, a brand of effrontery that had him delineating the ills of the legal profession before an audience of lawyers and cursing private power companies at a power plant dedication. In a profession where everyone avoided controversial issues and parsed each sentence, Scott was an anomaly who always spoke his mind. He never understood the value of no comment. In summary, Fentress praised Scott for stubborn and fearless commitment to his goals.1 Scotts impressive achievements changed the course of the Old North State and led to an industrial revolution and improved living conditions for all its citizens.

Up until 1948, North Carolina had been dominated by a powerful machine organization, known as the Shelby dynasty or the Gardner machine. Led by what V. O. Key Jr. called the progressive plutocracy,2 the machine consisted of an oligarchy of bankers and industrialists who dominated the states political and economic decision making. The Shelby dynasty favored sound, conservative government and maintained power by controlling the elective and appointive offices of the state administration. For twenty years, its members had, in effect, chosen the governor of the state. They were believers in the status quo and had access to the political funding that would keep them in power.

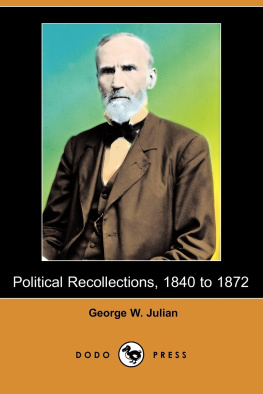

Governor W. Kerr Scott with his ever-present cigar. Photograph by Hugh Morton, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

Kerr Scott, a folksy, plainspoken, ambitious candidate, changed the power structure in the state in 1948 by winning one of the greatest political upsets in the states history. When he announced as a candidate for governor, very few gave the Alamance dairy farmer much of a chance, but he effectively mobilized his supporters with a populist attack on big business and a constant denunciation of machine politics. Farmers and the poorer element in the state believed that they had not been given their fair share of state largesse and grew tired of the conservative, business-dominated political system. Kerr Scott believed that, in a land of forgotten people, what was bad for two-thirds of the state was bad for the entire state. He understood the needs and desires of the states less fortunate citizens and rode their demand for improvement in their lives to victory in the race for governor. His defeat of Charlie Johnson, the state treasurer, ended a twenty-year reign of conservative machine politics in the state and changed the face of North Carolina politics. If Johnson, the chosen candidate of the progressive plutocracy, had prevailed, then North Carolina would be a far different state than it is today.

This book is focused on the contributions of Kerr Scott as governor from 1949 to 1953, but it is also the story of North Carolinas dramatic progression from a state not far removed from an introspective, backwater, segregated society dependent on tobacco and textiles into a vibrant, diversified global economy and the center of the industrial, banking, and information revolution in the South. Many of these changes took place during the ten-year period 19481958, when Kerr Scott held political office. When he took office, North Carolina had a per capita income that ranked forty-fifth of the then forty-eight states, an average school completion of 7.9 years, and a major problem with illiteracy. Sixty-six percent of the population lived in rural areas, and only one city had over 100,000 in population. There were no interstate highways, and only sixteen thousand miles of the states sixty-three-thousand-mile road system were hard surfaced. The state had no regional hospitals, no community colleges, and very few opportunities for advancement for those who lived in rural areas. Most of the rural folk lacked medical care, suffered from inadequate schools, and were isolated without telephones and electricity. In the legislative session of 1949, Governor Scotts progressive legislation to improve roads, schools, and medical facilities set in motion the changes that would lead to the states rise to prominence.

In 1948 the state had begun to change in many ways. There was a new mood of optimism among returning veterans and young people just beginning to vote. The state government had a large surplus accumulated during World War II to spend on citizens needs. World War II had a transformative effect on the state and set the stage for Scotts legislative successes. The massive government spending in the state for the purchase of farm and manufactured goods, along with the building of army and marine bases, gave a significant stimulus to the economy. The increase in shipbuilding and manufacturing led to many skilled jobs and a burgeoning urbanization.