This book was published with the assistance of the Luther H. Hodges Sr. and Luther H. Hodges Jr. Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2019 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Richard Hendel

Set in Utopia and TheSerif by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

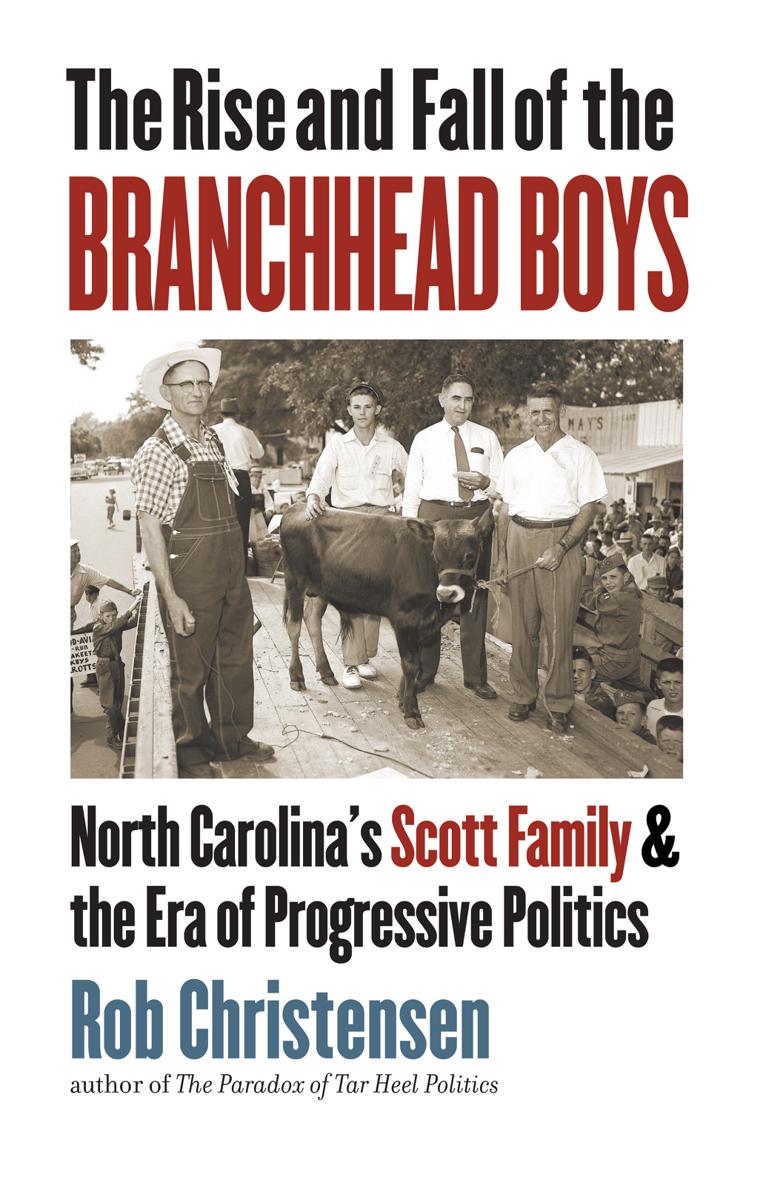

Jacket illustration: the Bull Calf Walk from Kerr Scotts 1954 Senate campaign; courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Christensen, Rob, author.

Title: The rise and fall of the Branchhead boys : North Carolinas Scott family and the era of progressive politics / Rob Christensen.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018049279 | ISBN 9781469651040 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469651057 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Scott family. | North CarolinaPolitics and government1951 | Progressivism (United States politics) | PoliticiansNorth CarolinaBiography.

Classification: LCC f260 .C577 2019 | DDC 975.6/043dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018049279

INTRODUCTION

Governor Kerr Scott was riding high when he arrived in the coastal town of New Bern to speak to the Young Democrats Club convention in September 1949. During his first nine months in office, Scott had launched a transformative road-building program, begun a major school construction effort, improved teacher salaries, pushed for extending electricity and telephone service to the countryside, and supported ongoing efforts to improve health care in the state. He had also shown himself an ally of blacks, women, and organized labor. He voiced support for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution for women and stood up to powerful corporations that ran the state.

In the process, Scott had outraged conservatives by naming liberals to high posts, whether it was an African American to the State Board of Education, the former press secretary of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman as the states Democratic National Commiteeman, or Frank Porter Graham, the president of the University of North Carolina and the Souths leading liberal, to the U.S. Senate.

Kerr Scotts accomplishments were also in service to the grooming of future generations of Democratic progressives like those in the Young Democrats Club at New Bern who gathered to hear him speak. The YDCs elected as their chairman Terry Sanford, a thirty-two-year-old Fayetteville attorney who would become Scotts heir apparent. Soon, a fifteen-year-old Jim Hunt, another future governor, would be ushered into Scotts office to have his photograph taken with the governor. Scotts own family would be part of the rural progressivism, toohis son Bob would follow him as governor; his brother, Ralph, would become one of North Carolinas most influential state lawmakers; his daughter-in-law would run for labor commissioner and lobby for the ERA; and his granddaughter would be elected agriculture commissioner. Speaking to about three hundred Young Democrats after a barbecue supper at the Trent Pines Club, Scott said that North Carolinas future rested in the hands of a liberal Democratic Party. He warned the Young Democrats to avoid getting yourself lined up with conservatism. Let us be an aggressive, progressive people. The Democratic Party should avoid putting any hindrance in the way of developing every resource. To return to conservatism would mean reestablishing new breeding grounds for Republicanism.

Among Scotts other admirers was Raleigh radio reporter Jesse Helms. In an off the record letter to the governor, Helms wrote, I think the present governor of North Carolina ought to set his cap for an even greater achievement. Our present governor, as far as I am concerned, is the first North Carolinian in my life time who has had the vision and the ability to become president of the United States. And he may represent North Carolinas only chance for that honor in my life time. Wont you have a heart-to-heart talk with the Governor in the hopes that he may set his cap for that accomplishment? This is the political era of the Little Man. You have a way of getting along with the little man. Make the most of it. It was signed, Admiringly, Jesse.

The North Carolina of 1949 was a far different place than the one today. It was among the most agrarian states in America, with two-thirds of the population living in areas officially designated as rural. The population was overwhelmingly composed of Tar Heel natives, and Charlotte, the largest city, was home to 134,930 people. The Sun Belt migration was decades in the future. But Kerr Scott, a rough-hewn dairy farmer from Haw River, helped foster a brand of rural progressivism that burnished North Carolinas reputation as among the most moderate and forward-looking in the South. As a result, for much of the second half of the twentieth century, North Carolina was led by Kerr, his son Bob, and their political allies, such as Terry Sanford, a lawyer from the small farming community of Laurinburg, and Jim Hunt, who grew up on a dairy farm outside Rock Ridge.

This was redeye-gravy progressivismnot big-city liberalism. Scott called his supporters Branchhead Boys, or those rural residents born at the head of a creek or branch. The movement was born among some of the nations poorest, most isolated farmers, nurtured in country churches, and powered by agriculture movements such as the Farmers Alliance and the North Carolina Grange, which welded the highly individualistic farmers into a single voice. When unleashed, the rural progressivism could erect great universities, build vast road networks, create new ports, force the utility companies to extend electricity and telephones into the countryside, and build housing for the poor. During Kerr Scotts term as governor, many rural North Carolinians saw government as a vehicle for improving their lives.

But at every step of the way, this rural progressivism was confronted by a deeply ingrained conservatismmuch of it emanating from those same fields and church pews. On the inflammatory question of racial equality, in particular, there was often a reactionary pushback. Well before Kerr Scotts time, during the Farmers Alliance and Populist push of the 1890s, the first wave of rural progressivism faced opposition in the form of the white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900. Likewise, Kerr Scotts Populist Go Forward program led to the racially charged Smith-Graham Senate campaign in 1950. And when his son Bob became governor, many came to distrust governmental power, especially when it came to forced racial integration of the public schools. Bob Scotts term as governor, from 1969 to 1973with its rise of black activismled to the election of sharply conservative Jesse Helms to the U.S. Senate.

What happened in North Carolina is not unique to the state or even to the South. The progressive ruralism of the Midwest and the Westthe phenomenon that gave rise to such movements as the Populist Party and organizations such as the Grange and the National Farmers Alliancefaded with time. Indeed, the small, embattled farmerthe Branchhead Boy supporter of Kerr Scottbegan to disappear as far fewer people earned their living from the land and farming became more mechanized and corporate.