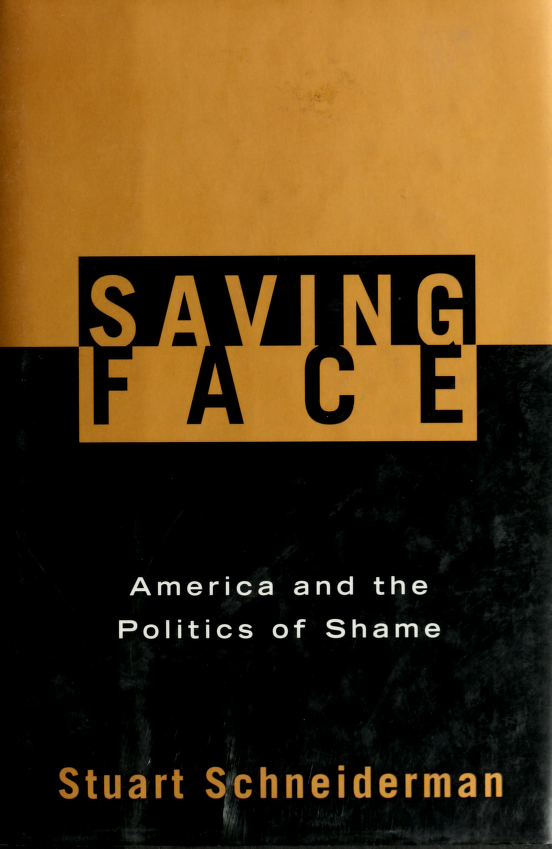

Saving face : America and the politics of shame

Saving face : America and the politics of shame

Schneiderman, Stuart, 1943

This book was produced in EPUB format by the Internet Archive.

The book pages were scanned and converted to EPUB format automatically. This process relies on optical character recognition, and is somewhat susceptible to errors. The book may not offer the correct reading sequence, and there may be weird characters, non-words, and incorrect guesses at structure. Some page numbers and headers or footers may remain from the scanned page. The process which identifies images might have found stray marks on the page which are not actually images from the book. The hidden page numbering which may be available to your ereader corresponds to the numbered pages in the print edition, but is not an exact match; page numbers will increment at the same rate as the corresponding print edition, but we may have started numbering before the print book's visible page numbers. The Internet Archive is working to improve the scanning process and resulting books, but in the meantime, we hope that this book will be useful to you.

The Internet Archive was founded in 1996 to build an Internet library and to promote universal access to all knowledge. The Archive's purposes include offering permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format. The Internet Archive includes texts, audio, moving images, and software as well as archived web pages, and provides specialized services for information access for the blind and other persons with disabilities.

Created with abbyy2epub (v.1.7.0)

America and thePolitics of Shame

Stuart S'phneiderman

m

FPT U.S.A. $25.00Canada $35.00

In this original and timely book, Stuart Schneidermanexplores and analyzes the forces of shame (when youdo not do something you are supposed to do) asopposed to guilt (when you do something that you arenot supposed to do), and shows how both cruciallyaffect a culture, a society, an institution, a marriage, theself.

Schneiderman defines a shame culture as one inwhich group cohesion is more important than individ-ual expression, where the behavior of an individualreflects well or badly on the group reputation (militaryorganizations, corporations, families). He defines aguilt culture as one in which the group is not responsi-ble for an individual's misdeeds, where individuals areencouraged to act with the greatest freedom and arefree to pursue a course of action that will assure thesoul's salvation.

He shows how a shame culture educates by per-suading people to do things the right way and to be mo-tivated by duty to preserve their honor and reputation,and how a guilt culture educates by instilling a fear ofthe consequences of doing the wrong thing.

While Japan has been described as a shame cultureand the United States as a guilt culture, Schneidermanexplains how America in the past has been, and inmany ways needs to be, a shame culture. He arguesthat we have become a guilt culture and how it hasaffected our society. He traces the two philosophies inthis country to Alexander Hamilton, the Federalistwho believed in industry, capital markets, and trade,and who placed the union over individual states, and toThomas Jefferson, the Liberalist who favored individ-ual liberty and democracy. Schneiderman adds howAlexis de Tocqueville observed the way shame inAmerica was used to promote hard work and familycohesion.

He discusses why Freud invented psychoanalysisas a theory of guilt and why it has been so seductive.

Qii 3 03

$4.00

Digitized by the Internet Archivein 2010

http://www.archive.org/details/savingfaceamericOOschn

ALSO BY STUART SCHNEIDERMAN

Jacques Lacan

Rat ManAn Angel Passes

SAVINGFACE

For my mother and my father

Washington... deplored the adversary theorywhich sees government as a tug-of-war betweenthe holders of opposite views, one side eventuallyvanquishing the other. Washington saw the na-tional capital as a place where men came togethernot to tussle but to reconcile disagreements.

JAMES THOMAS FLEXNER

Manners are of more importance than laws. Uponthem, in a great measure, the laws depend. Thelaw touches us but here and there, and now andthen. Manners are what vex or soothe, corrupt orpurify, exalt or debase, barbarize or refine us, bya constant, steady, uniform, insensible operation,like that of the air we breathe in. They give theirwhole form and color to our lives. According totheir quality, they aid morals, they supply them,or they totally destroy them.

EDMUND BURKE

The English, more than any other people, notonly act but feel according to rule.... The greaterpart of life is carried on, not by following incli-nation under the control of a rule, but by havingno inclination but that of following a rule.

JOHN STUART MILL

In the past and up to the very present, it hasbeen a characteristic precisely of the specificallyAmerican democracy that it did not constitute aformless sand heap of individuals, but rather abuzzing complex of strictly exclusive, yet vol-untary associations. max weber

Contents

Introduction 3

1. A Conflict of Cultures? 19

2. Facing Trauma: America in Vietnam 59

3. The Great American Cultural Revolution 99

4. Family Secrets 144

5. Love and Marriage 194

6. The New Face of Psychotherapy 241

Acknowledgments 293

Notes 295

References 303

Index 313

SAVINGFACE

Fresh from her victory in the Cold War, America awoke to findherself confronted with a new and, in many ways, more difficultchallenge. This other strugglefor money and marketshadbeen going on for years: the nation had been engaged in economiccompetition against Japan and the rest of the nations of the FarEast.

Moreover, we seemed to be losing. At the close of the Amer-ican century we could no longer assume that everyone would haveto play by our rules." Alarmists were even predicting that the nextcentury would belong to the Pacific Rim.

For a time Japan seemed to be like an octopus. A large headlocated on a small island sent out tentacles that stretched aroundthe globe in a "diaspora by design."^ As the 1990s dawned, theJapanese "bubble" economy had burst, however, and the bloomwas off the chrysanthemum.

Even so, from 1965 to 1990 Japan and the leading nations ofthe Far East enjoyed economic growth rates that far outdistancedthose of any other part of the globe. According to the World Bank,

SAVINGFACE 4

Japan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea,Taiwan, and Thailand had an average annual growth rate that wasmore than double those of both the developed and the developingworld. And these nations, hardly the most democratic, also main-tained the most equitable distribution of income.^

Throughout the Far East Japan had already supplanted Amer-ica as the nation to emulate. As Deng Xiaoping's China modeleditself on the Japanese postwar success and became the world'sfastest growing economy, the newly democratized Russia enteredinto an economic free fall. While some were proclaiming the finalvictory of Western liberal democracy, others feared that theUnited States was about to become a Third World nation. Bothwere no doubt exaggerated.

To defend democratic values we began to denigrate the FarEastreveling in each story of Japanese corruption and Chinesedespotism. We consoled ourselves by thinking that in some finaltriumph of justice we would win and they would be punished.Perhaps that was why we continued to produce far more lawyersthan engineers, while Asian nations were turning out far moreengineers than lawyers.

Next page