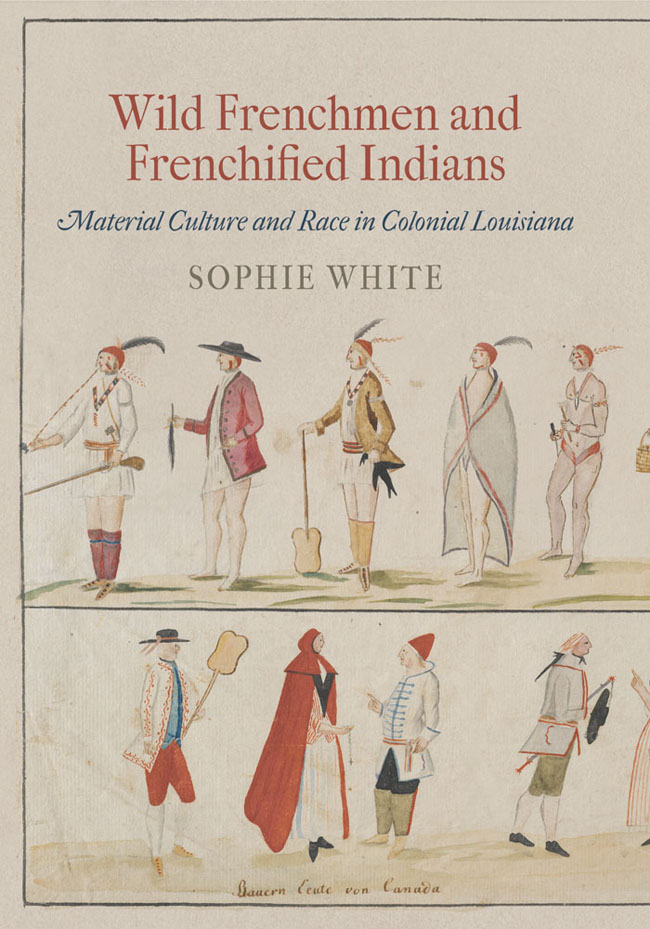

WILD FRENCHMEN AND

FRENCHIFIED INDIANS

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max

Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is

available from the publisher.

WILD FRENCHMEN AND

FRENCHIFIED INDIANS

Material culture and Race

in colonial Louisiana

SOPHIE WHITE

PENN

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

For Charlie, Cleome, and Josephine

Copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the united states of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of congress cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, sophie.

Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians : material culture and race in colonial Louisiana / sophie White. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

ISBN 978-0-8122-4437-3 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. FrenchLouisianaHistory18th century. 2. Indians of North AmericaLouisianaHistory18th century. 3. LouisianaRace relationsHistory18th century. 4. Race awarenessLouisianaHistory18th century. 5. Material cultureLouisianaHistory18th century. 6. clothing and dresssocial aspectsLouisianaHistory18th century. I. Title. II. series: Early American studies.

F380.F8W55 2012 |

976.302dc23 | 2012014401 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

FIGURES

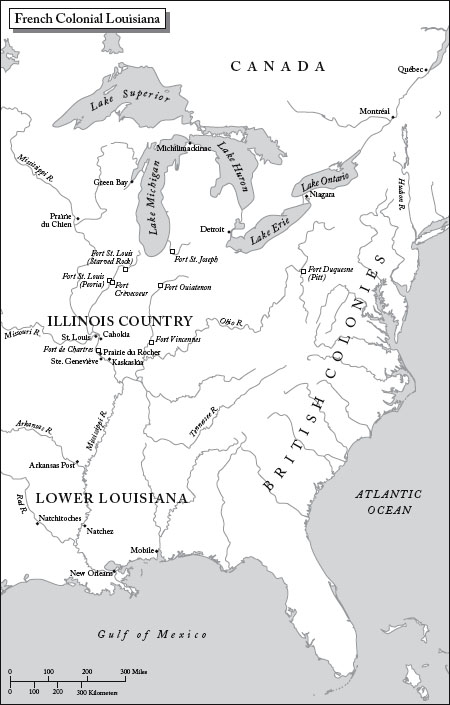

1. French Colonial Louisiana

PLATES

1. de Batz, Dessein de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations

2. Bequette-Ribault House Ste. Genevieve, Missouri

3. Cahokia Courthouse Cahokia, Illinois.

4. French faence, Fort de Chartres III

5, 6. Womans Bed Gown and petticoat (and detail).

7. Toilles de Cotton peintes Marseilles 1736 Indiennes ou Guines

8-13. Lady Clapham Doll (and details).

14. Anonymous, Genre Study of Habitants and Indians

15. Stretton, Canadian man & woman in their winter dress

16. Broutin, Elevation qui entourre la Poudriere

17. Calimanco (Calemande) textile sample

18. Quilted and padded bodice (jumps)

19. Dumont de Montigny, Sauvage... Sauvagesse.

20. De Batz, Sauvages Tchaktas matachez en Guerriers

21. Von Reck, Indian King and Queen of Uchi

22. De Batz, Sauvage en habit dhyver.

23, 24. Anonymous, Three Villages robe (and detail)

25. Broutin, Plan de la Nouvelle Orleans

26. Mans Shirt, Lord Clapham doll

27. Samples of Siamoises

28, 29. Le Bouteux, Vee du camp de la concession (and detail)

30. Cloth, buttons, button loops, La Belle shipwreck

31. Masquerade mask, Lady Clapham doll

32. Dumont de Montigny, Manierre et representation dun cadre

33. Dumont de Montigny, Plan de la Nlle Orleans

WILD FRENCHMEN AND

FRENCHIFIED INDIANS

Figure 1. French Colonial Louisiana.

Introduction

In eighteenth-century French colonial Louisiana, Marie Catherine Illinoise, an Illinois Indian woman convert who was legally and sacramentally married to a Frenchman in the Upper Mississippi Valley, could be found dressed in one of her silk taffeta gowns as she sat in an armchair in her home built in the French colonial architectural style. Born Illinois, she was now Frenchified and was categorized in official records as French. This womans material culture testifies to the transformations engineered by French and Indians as a result of colonization, conversion, and mtissage (the mixing of peoples). For there were numerous other instances of French-Indian exchanges and cross-cultural dressing in Louisiana.

In fulfilling her wish to take her vows as a Catholic nun in New Orleans, Marie Turpin, born from a French-Indian union, would cement her acquisition of a new identity and name through the wearing of special religious attire. A voyageur (canoeman or fur trader) of mixed French-Indian heritage, Jean Saguingouara, would enter into a formal agreement to go to New Orleans and back; other than his wages, he negotiated for his linens to be laundered on arrival in that town. In the same year that this trader traveled down the Mississippi River, Antoine Philippe de Marigny, Sieur de Mandeville, a French military cadet of noble origin, underwent a reverse transformation, donning Indian garb to traverse the hinterlands. In each of these anecdotes, clothing offered an especially elastic, protean means of expression. Through the act of dressing, indigenous peoples and settlers found the means to consciously express themselves even as they bought into, or were forced into, colonizations material underpinnings. For colonization in early America was built on encounters mediated by appearance, placing clothing at the center of cross-cultural relations and speaking to the vitality of cultural exchanges made visible on the body.

Analyzing the contours of French-Indian cultural cross-dressing I use identity as a category of analysis to shed light on how the French in America viewed the savages and formulated Frenchness.Indian wife, the nun, the trader, and the cadet provides insights into their consumption of material goods, specifically dress, and their skill in donning and wearing the clothes. But how these people lived and how they looked also influenced the way they were perceived. That colonial authorities could classify an Indian-born woman as French, for example, raises the question whether her manipulation of goods determined her credentials (in the eyes of the French) as French or sauvage. Such sartorial exchanges raise fundamental questions about how subjectivity was defined and constructed. They also problematize the process whereby identity was explained during a period when French conceptions of difference were in transition, in a colony where policies toward Indians were colored by preoccupations with religion and acculturation, and inflected by the establishment of African slavery.

While this book illuminates the agency of Native Americans and Europeans as they encountered and absorbed each others goods, it foregrounds colonists rather than Indians conceptions of difference. I argue that appearance influenced the ways the French understood and theorized ethnic, and later racial, identity. Dress was never simply a matter of self-expression but a cultural act subject to interpretation by onlookers. Over the course of the French regime, from 1673 to 1769, there was a transition from a conception of identity as fluid and mutable, to an essentialist conception based on proto-biological assumptions. How individual Indians living in French settlements dressed, I aver, had an impact on whether colonists hung on to older views of ethnicity as mutable, or subscribed to new models of a fixed and inborn racial identity for Indians. My book recognizes the complex geopolitical factors that paved the way for racialism. But it also underlines that there was no smooth transition to racialization, and that material culture served to complicate the ascendancy of a hegemonic protobiological model of difference in the colony as applied to Indians. For, as a genre of cultural expression, material culture did not simply reflect difference. It also helped to produce it. My analysis thus offers an innovative reading of the contours and the chronology of racialization in early America.