Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

SLAVES FOR PEANUTS

A STORY OF CONQUEST, LIBERATION, AND A CROP THAT CHANGED HISTORY

Jori Lewis

Contents

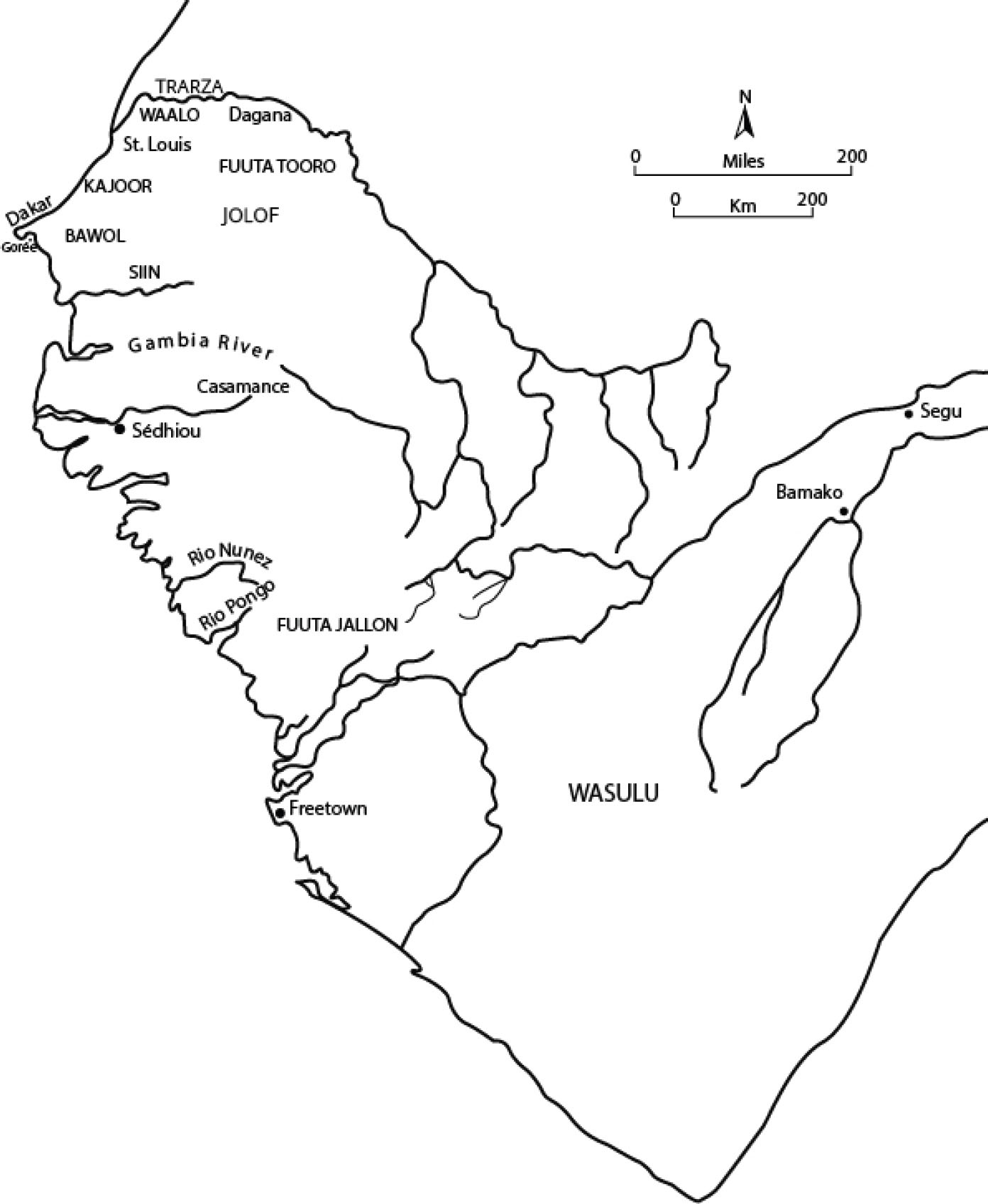

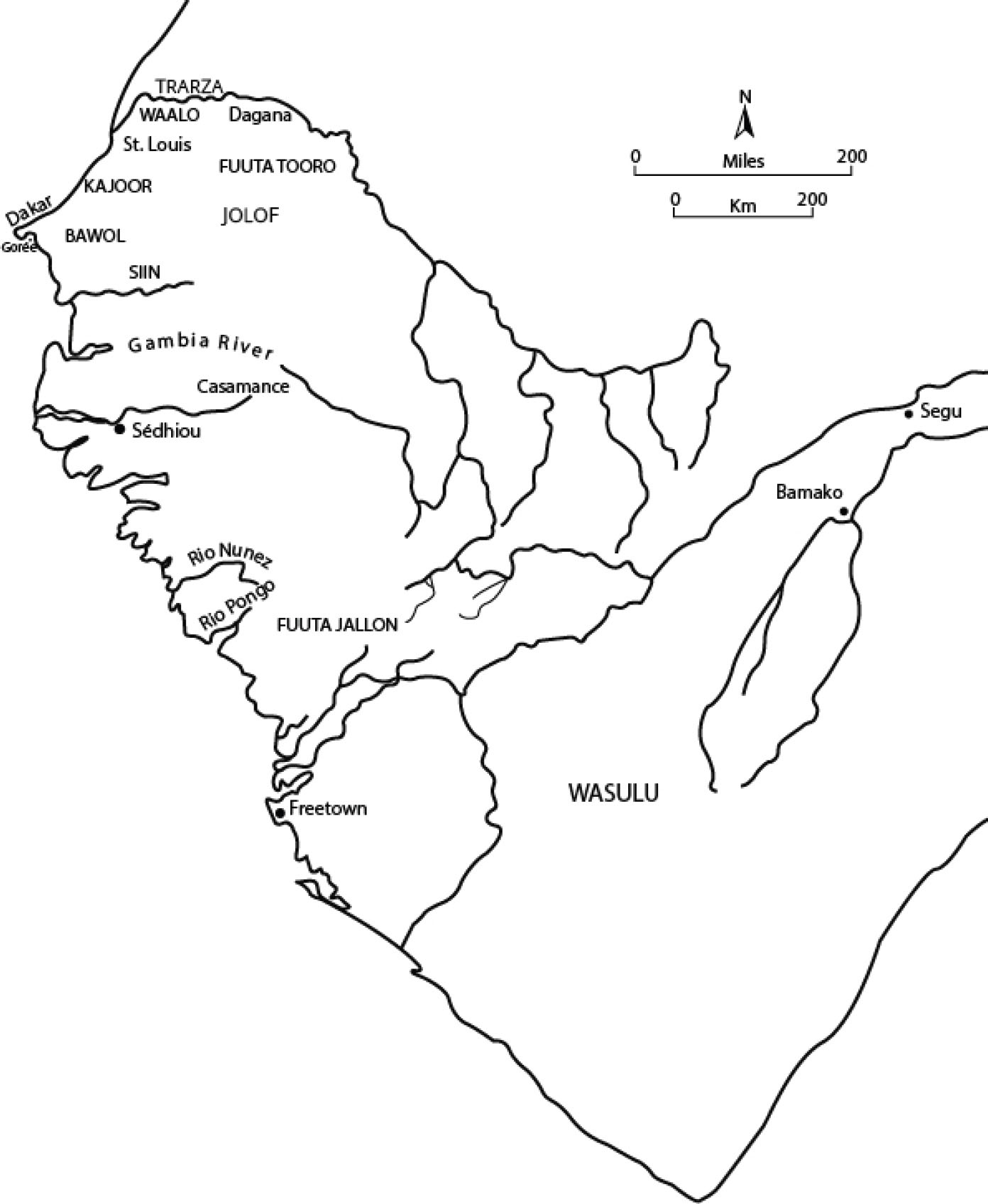

Western Africa

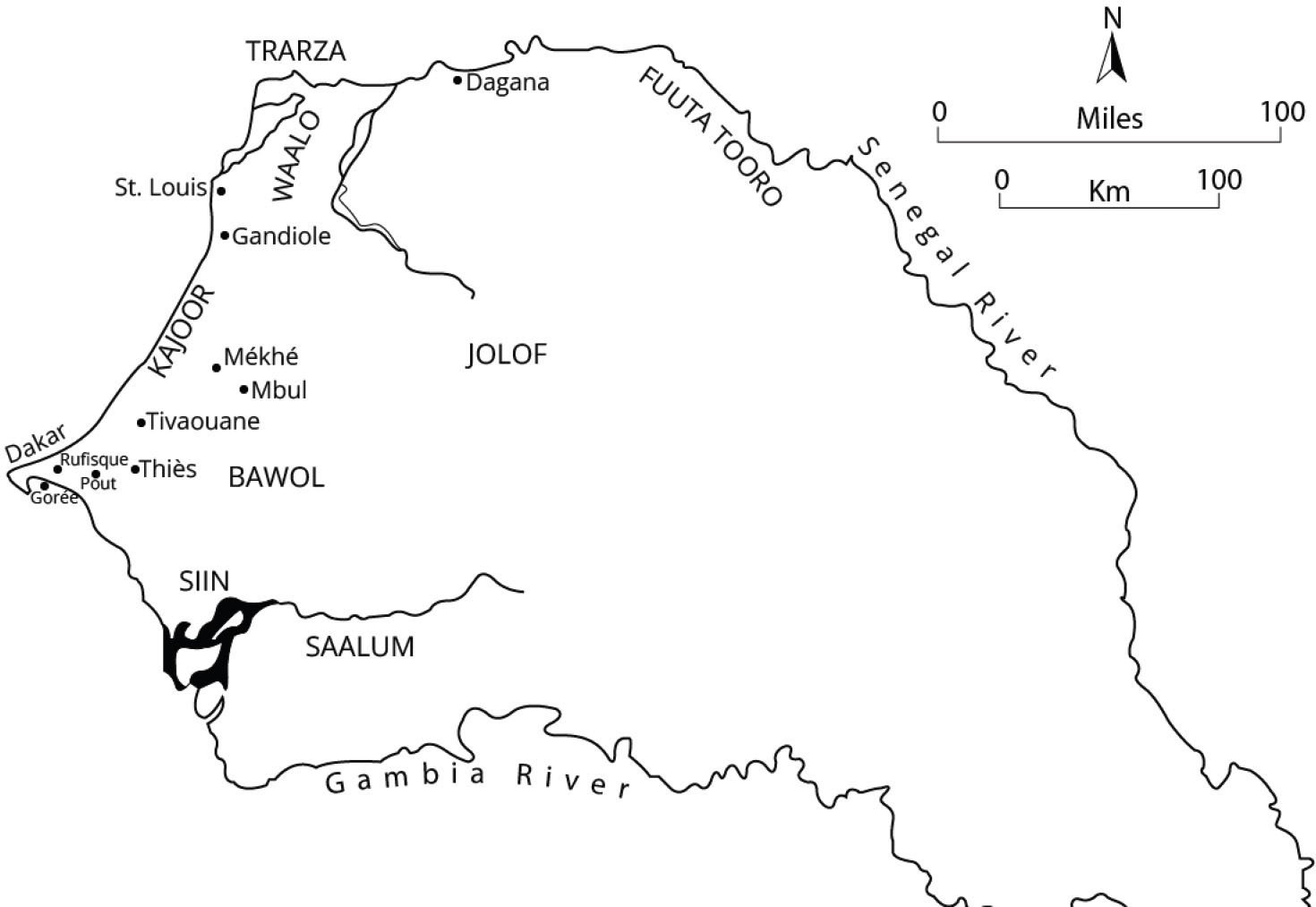

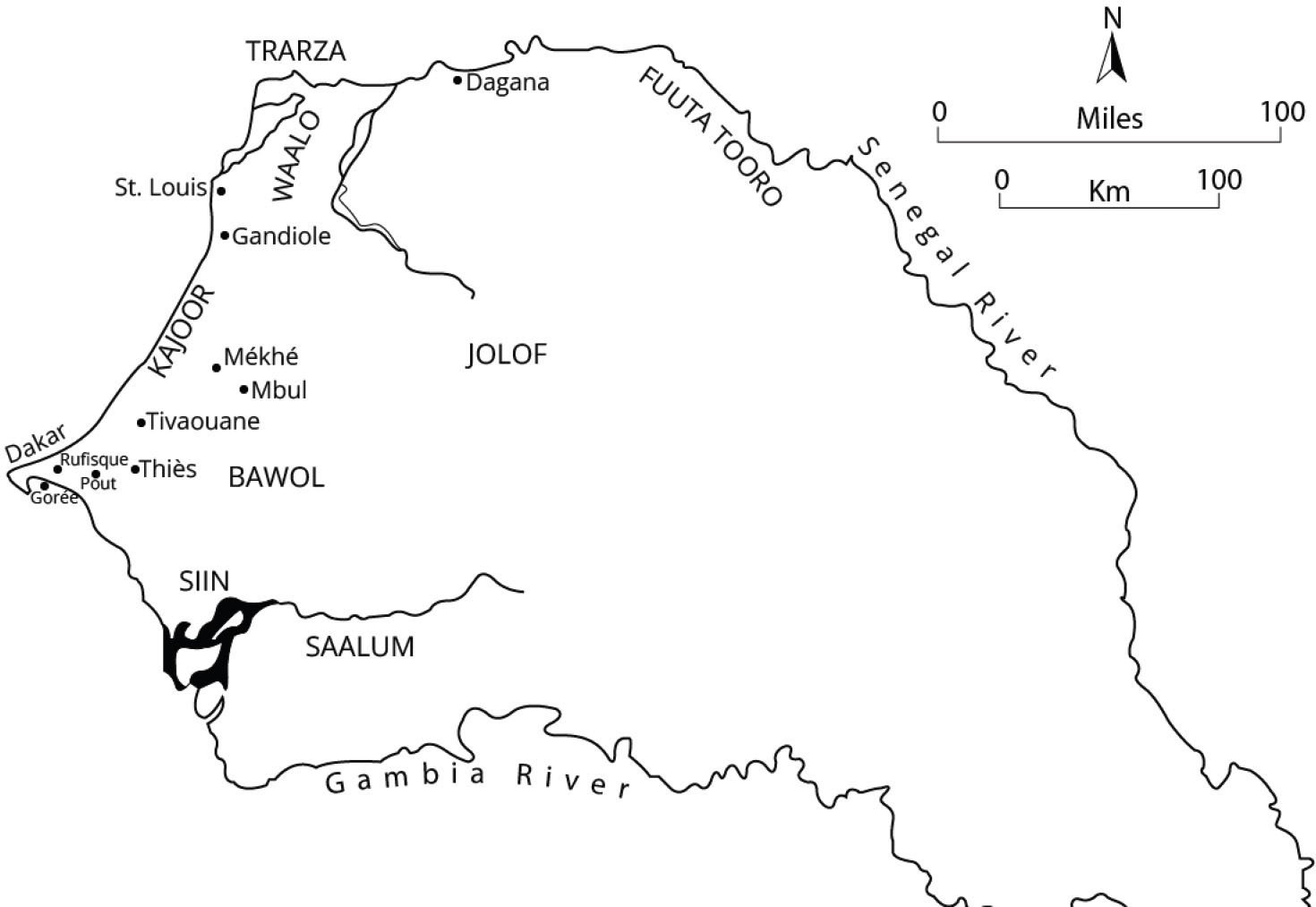

Senegambia

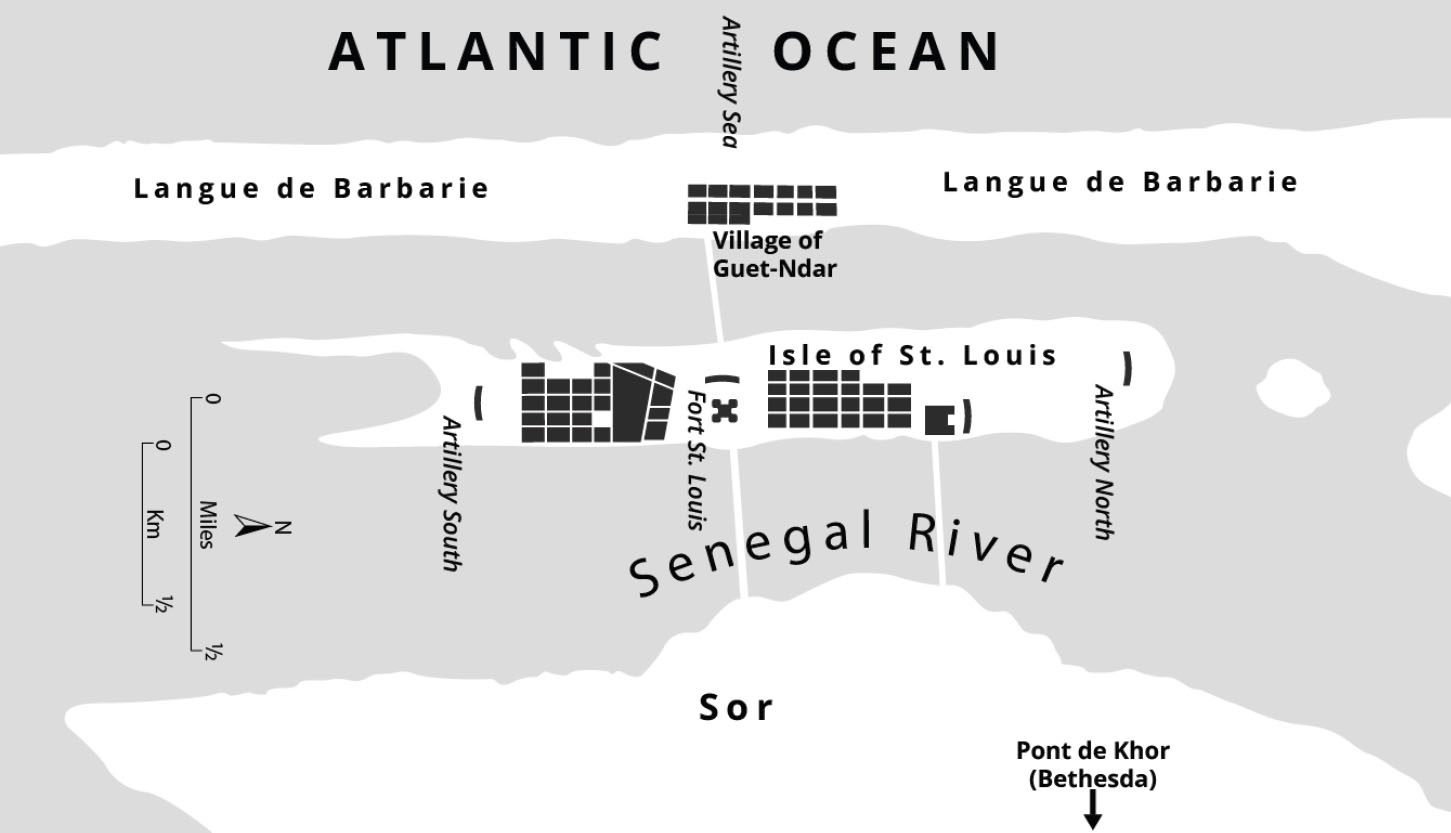

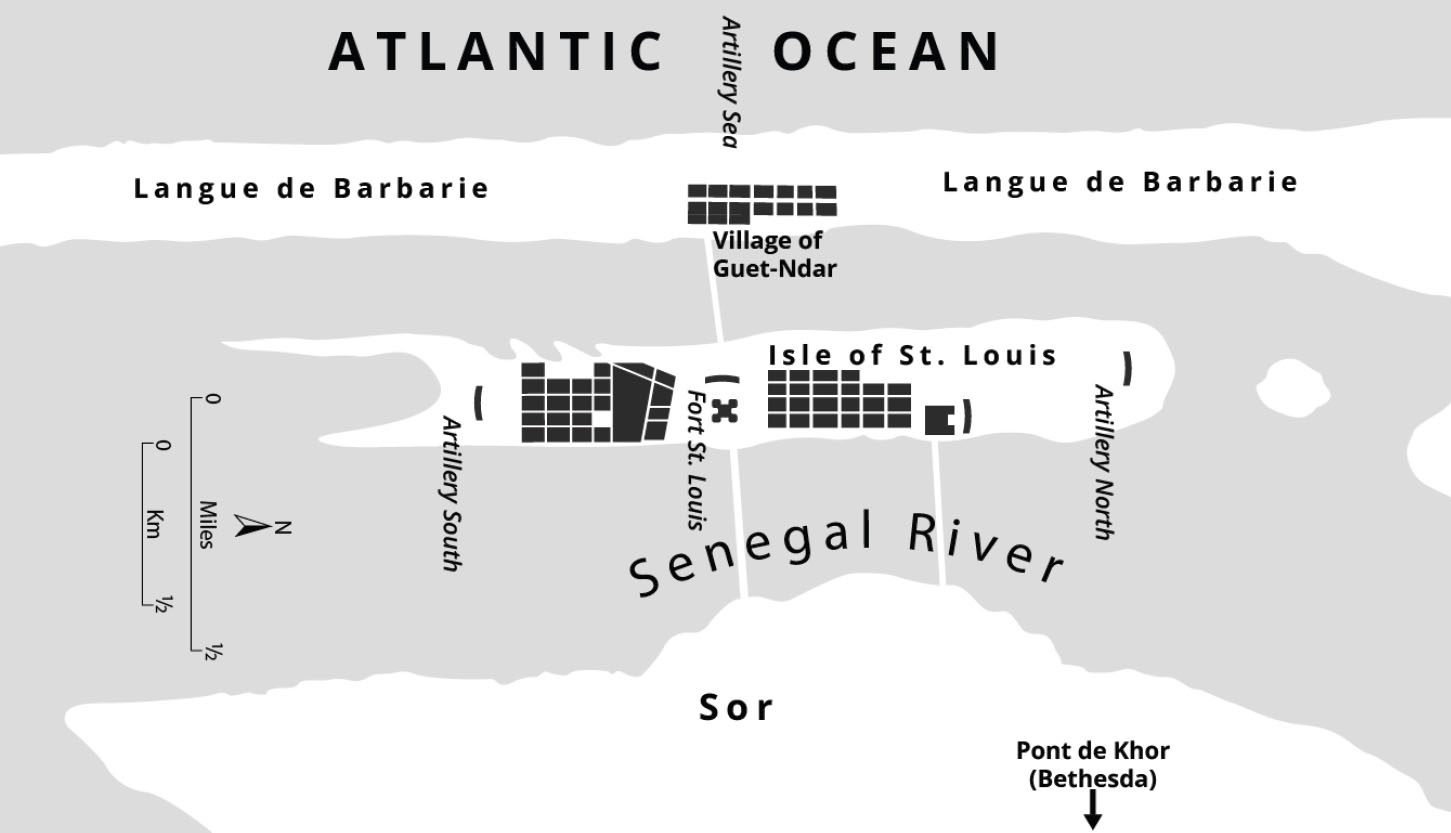

Saint Louis

Preface

I had never seen a peanut grow until I went to Senegal. Im told that Papa Lewis, my great-grandfather, had grown peanuts on his Arkansas farm, along with okra and corn, soybeans and cotton, but he died long before I was born. His son, my grandfathers elder brother, must have predicted what was coming for American agriculture early on, and pulled out his mixed cropping system to focus on soy and cattle alone.

I still associate peanuts with that Arkansas family, though, because I remember always coming back from our vacations there with bags of freshly roasted peanuts nestled in their tan shells, but I guess we bought them at someone elses farm stand. Peanut snacking was a regular occupation as we drove the seven or eight hours back to Illinois, cracking open the shells to pop the peanuts into our mouths. Sometimes I would suck on the shell for extra salt while I stared out the window, watching the topography change: from the rice fields that sat low along the rivers; to the spiky hills of the Ozarks, half forest and half rock; and finally back to the flat landscapes I knew best, a glance at the horizon yielding unvarying glimpses of lonely farm houses in the middle of fields of corn whose stalks had grown twice as tall as any man.

Those flat vistas from my childhood always flash through my mind on my trips through Senegals main agricultural zones, where plots of millet and peanuts occupy a procession of fields broken up only by a tree here or there, or a parade of wandering cows. It was in one such field that I first espied the peanuts tiny flowers, the color of sunshine and so similar in shade and size, if not in form, to the buttercups I used to pick in our yard as a child. Nothing else was familiar, though: not the horse-drawn plows, not the sight of people bending to harvest peanuts by hand, not the work songs of the men who came from Guinea-Bissau to separate the stems and leaves from the shells, not the great mound of peanuts outside the peanut oil factorypiled so high it could block out the sun.

I had been interested in how something as humble as the peanut had acted as the motor of the Senegalese economy for so long; for more than a century this small country had been one of the top producers of the oily legume in the world. It was only an offhand comment by a future ex-boyfriend, an agronomist, that pushed me down a slightly different path. One day, he was telling me about one of the villages where he worked, where the farmers were organizing a collective. They had decided to exclude a smart and capable man from a leadership position, a man I had met on trips to the region, who was the person objectively most qualified for the job. They had excluded him because he was known to be descended from people who had once been enslaved. I flinched when I heard this. As a descendant of the enslaved myself, I found it both painful to hear about this discrimination and difficult to understand.

In trying to make sense of this, in trying to understand the reasons and justifications, I started to search for other descendants of slavery, both in those peanut lands and in regions farther afield: in mud houses in the village, in reed-lined fields that hugged the river, and in high-rise apartments in Dakar. Eventually, my search and attempt to find out more led me to a series of historical records.

I would have liked to say that I was able to resurrect the voices of those who had been enslaved. But writing a historical narrative about the enslaved is complicated because there are multiple layers of silences. There is the fundamental silencing of Indigenous voices in the colonial archives, which privilege those of European officials. And many of the available epic poems or oral histories that have been passed from generation to generation often tell the stories of societys elitesthe kings, nobles, warriors, and important religious leaders. Women rarely feature, and the enslaved almost never; they are muted, and the distance of a century reveals only flickering, spectral forms. How do we tell the stories of people that history forgets and the present avoids?

I have tried here to uncover a handful of stories about a handful of people. I wish I could have done more.

Part I

1 A Shelter for Runaway Slaves

, the official weekly newspaper of the colony of Senegal noted that a certain Moussa Sidib had claimed his freedom at the age of twenty-five. Le Moniteur du Sngal et Dpendances regularly revealed the names of the formerly enslaved men, women, and children who had been given their freedom papers in the past month. It was official business of the court, nestled between colonial decrees, bankruptcy announcements, weather tables, and ads for ferruginous lemonade and quinine elixirs. The newspaper listed them by date of liberation and included their ages, the name of the person who had registered them, and their destination. In the case of minorsfor many of the newly freed were childrenthe destination was a person; a child would be entrusted to a mother, a father, or a guardian. For an adult former captive, though, the destination was figurative.

For Moussa Sidib on May 27, 1879, the newspaper listed him as delivered to himself.

There were at least two other Moussa Sidibs listed as claiming their freedom in 1879: a forty-year-old who had been liberated on January 3 and a thirty-year-old on August 12. the one who was a younger man, just twenty-one, when he fled to the colonial capital of Saint Louis, looking for his freedom?

That Moussa Sidib had come from the neighboring kingdom of Kajoor, where, he said, he had been enslaved for the past five years. I was obliged to serve an excessively harsh master, he later said, who made every effort to make my life bitter.

________

, live, and die free and French.

When Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France, though, he disagreed; he wanted Saint-Domingue to be French, of course, but he did not want everyone to be free. Starting in 1802, a series of laws and decrees would re-establish slavery across the French Empire. But the people of Saint-Domingue refused, resisting with all their might, even after Napoleons forces captured and deported Toussaint Louverture to France, where he later died. The war hemorrhaged men and money until the French were forced to concede, and the colony formerly known as Saint-Domingue was born anew as the Republic of Haiti.

called the long-established institution of slavery into question and inspired, through admiration and fear, discussions about emancipation across the Atlantic world. Memories of the slave rebellion in Haiti must have haunted legislators and parliamentarians in the United States and Great Britain and influenced them as they banned the trans-Atlantic slave trade for their ships and citizens in the years that followed.