Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2015 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Ryan Morris

Marketing, Kate R. Seburyamo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Laukaitis, John J.

Community self-determination : American Indian education in Chicago, 19522006 / John J. Laukaitis.

pages cm. (SUNY series, Tribal Worlds: Critical Studies in

American Indian Nation Building)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5769-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-5770-3 (e-book)

1. Indians of North AmericaEducationIllinoisChicagoHistory. 2. Indians of North AmericaIllinoisChicagoHistory.I. Title.

E97.65.I5L38 2015

371.829'97077311dc23 2014040650

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Victor and Rose Laukaitis

Preface

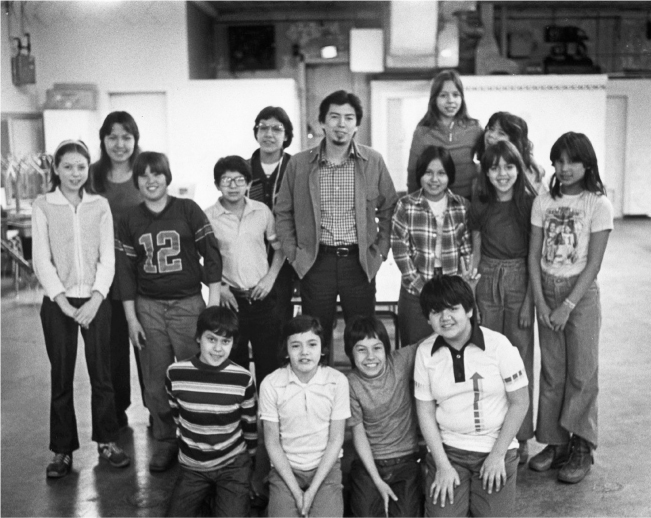

On an unseasonably cool August day in 2009, I attended the dedication of a mural on Chicagos North Side titled Indian Land Dancing, after a poem by E. Donald Two-Rivers (Ojibwe). The mural transformed a drab urban space into a vibrant visual history of the citys American Indian community. The walls of the Foster Avenue underpass at Lake Shore Drive presented a bricolage of photographs, drawings, and mosaics that paid tribute to well-known American Indians associated with Chicago and lesser-known American Indians who dedicated much of their lives to serving others in the city. The juxtaposition, for instance, of Maria Tallchief (Osage), a former prima ballerina with the New York City Ballet and founder of the Chicago City Ballet, and Edith Johns (Ho-ChunkNez Perce), a former registered nurse and the first caseworker at St. Augustines Center for American Indians, called attention to the diversity of people who have, in so many ways, woven the fabric of the community over its history. The walls of the underpass, however, could never show all who deserve to be remembered. Simply stated, there are too many. From the American Indian families who lived in Chicago prior to World War II and assisted the influx of people arriving from reservations in the 1950s to the individuals who made the growth of grassroots programs possible in the 1970s, the history of Chicagos American Indian community is largely one of unsung people working collectively to maintain a sense of cultural identity and livelihood within an urban context.

As I began researching the history of American Indian educational programs in Chicago, I learned that it could not be understood without first understanding Native concepts of community. Louis Delgado (Oneida), who directed O-Wai-Ya-Wa Elementary School and the Community Board Training Project at Native American Educational Services (NAES) College, shared an insight with me that began shaping how I approached writing this book. When I met with Delgado in 2006, I prefaced a question with, As a leader in Chicagos American Indian community. He Over the course of many years, I came to realize and appreciate how the value of community largely directed the actions of individuals. The American Indians who came to Chicagomany prior to the federal relocation programcarried with them their deep compassion for the well-being of others, and this compassion extended beyond tribal affiliations to include all of those in the community and all of those continuing to arrive. I was fortunate to meet Delgado, Power, and others, for they guided this work by moving the community to the foreground.

This book began with my broader interest in how ethnic groups form and utilize educational programs for community self-preservation in urban areas. When I came across an article titled Native Land: American Indians Leaving Uptown Behind in The Chicago Reporter in 2002, I was surprised to learn that Chicago had a significant American Indian population. While American Indiansto employ a commonly used ascriptionare an invisible minority in Chicago, they, by 1960, constituted one of the largest American Indian populations living in a metropolitan area. My initial inquiry at the Newberry Library in Chicago under the suggestion of Dr. Josef Barton at Northwestern University acquainted me with Dr. Brian Hosmer and Dr. Dan Cobb, the former director and former assistant director, respectively, of the institutions DArcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian. Through their advice, I eventually contacted Dr. Dorene Wiese (Ojibwe), president of NAES College, and our conversations made me aware of the extensive and rich history of American Indian educational programs in the city. In the years that followed, I spent countless days in NAES Colleges archives and the archives of various institutions absorbed in researching the history of these community-based initiatives and, more importantly, understanding their significance within the history of American Indian education and the American Indian self-determination movement.

Over time, I met many members of the American Indian community and those involved in the various organizations and programs for American Indians. I listened to what they had to share. Listening became an important component of my research, and the oral history interviews Using a methodology that joins conventional sources of documentation and oral history ultimately offers a greater potential for understanding the facts, feelings, and meanings of the past. The more I examined boxes of documents and listened to a multitude of voices, the more I realized the essential worth of each mode of research in writing a more complete history. In addition to the American Indian voices present in this book, I also included the voices of non-Indians. Their memories and perspectives were essential to this work, too. I was fortunate in having the support of a wide scope of individuals who believed in the potential and importance of a book focusing on the history of American Indian educational programs in Chicago, and I am grateful for the time they gave as well as their trust in me to write it.

As I look back on the experience of writing this book, I only regret that I did not have the opportunity to meet the many individuals who passed away but whose influence remains intact to this day. I only know people such as Babe Begay (Navajo), Ben Bearskin Sr. (Ho-ChunkSioux), Ernest Naquayouma (Hopi), Willard LaMere (Ho-Chunk), Annie Pleets Harris (Sioux), Al Cobe (Ojibwe), Hiawatha Hood (Yavapai), Robert K. Thomas (Cherokee), Robert V. Dumont Jr. (Assiniboine), Dennis Harper (Ojibwe), Sol Tax, Robert Rietz, Dorothy Van de Mark, and Armin Beck through the words of others and the written records of their thoughts and lives. I hope this book is worthy of their memory and reveals the extent to which they promoted a vision of Native community in Chicago. These individuals deserve to be remembered for the vital role they played in keeping a community alive even through dark moments.