Contents

Page List

Guide

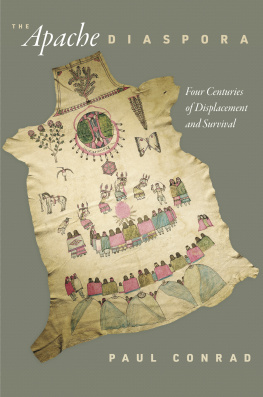

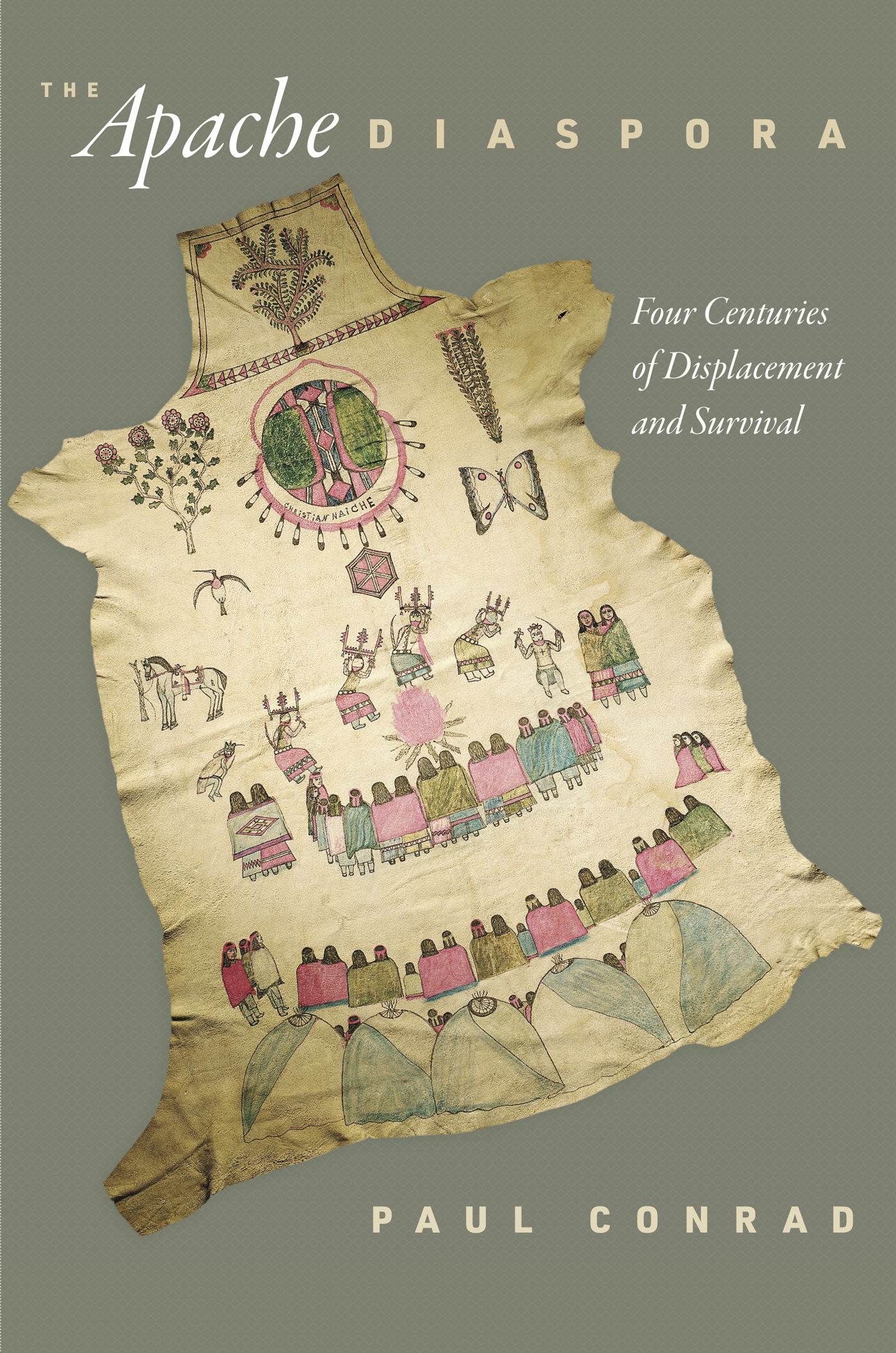

The Apache Diaspora

AMERICA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Series editors

Brian DeLay

Steven Hahn

Amy Dru Stanley

America in the Nineteenth Century proposes a rigorous rethinking of this most formative period in U.S. history. Books in the series will be wide-ranging and eclectic, with an interest in politics at all levels, culture and capitalism, race and slavery, law, gender, and the environment, and regional and transnational history. The series aims to expand the scope of nineteenth-century historiography by bringing classic questions into dialogue with innovative perspectives, approaches, and methodologies.

The Apache Diaspora

Four Centuries of Displacement and Survival

Paul Conrad

Published in Cooperation with the

William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies,

Southern Methodist University

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLYANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2021 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Conrad, Paul, author.

Title: The Apache diaspora : four centuries of displacement and survival / Paul Conrad.

Other titles: America in the nineteenth century.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021. |

Series: America in the nineteenth century | Published in Cooperation with the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020037029 | ISBN 9780812253016 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Apache IndiansHistory. | Apache IndiansMigrations. | Apache IndiansRelocation. | Apache IndiansGovernment policy. | Apache IndiansEthnic indentity.

Classification: LCC E99.A6 C595 2021 | DDC 979.004/9725dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020037029

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Fantastic and Terrible Stories

Everyone laughed at the impossibility of it,

but also the truth. Because who would believe

the fantastic and terrible story of all of our survival

those who were never meant to survive?

Joy Harjo, Anchorage

A young man walked the grounds of a school counting graves. He had been sent to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1898 for an education, to be trained in welding, construction, and other industrial skills. As he passed through rows of gravestones, counting to 105 before he got mixed up, he learned other lessons. Very few came back, he observed.

Sam Kenoi was one who did, however. He slipped away one night on a westbound train and returned to his people. At this time, his Apache Indian relatives were U.S. prisoners of war and had been since the army rounded them up from their Arizona reservation in 1886 and shipped them into exile in Florida, Alabama, and then Oklahoma. Kenoi married and started a family. He settled on the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico after Apache POWs were finally freed in 1913 and given a choice of where to live. After his first wife died of pneumonia, he remarried and had more children. He organized his people in a bold effort to seek reparations for their twenty-seven-year internment.

Most lives are full of tragedy and triumph, and Kenois was no exception. But his life was also particular, shaped by who he was as an Apache. Kenoi confronted challenges that his ancestors had faced for generations. How does one exist in a world that does not want you to exist as you are? How does one survive that which so many are not surviving? How does one start over in a foreign land or on land made foreign by colonialism? Kenoi responded to these questions creatively, pushed back on those who mistreated him, and lived boldly within the constraints of his circumstances.

Pulling back from Kenois particular story, a broader portrait of Apache life and death across North America and the Caribbean comes into view. Apache men and women throw themselves into the Gulf of Mexico, desperate to escape the boat waiting to carry them overseas. A priest pens an entry in a leather-bound ledger near the Pacific coast of Sonoraanother Apache girl buried after months of forced labor. Apache boys run errands for the governor of Quebec, and Apache women gather water for their masters at a neighborhood well in Mexico City. Apache men pull a pine tree out of the chimney of an old U.S. fort in Florida and apply mortar to Spanish fortifications in the port of Havana. An Apache servant and a black slave marry in a church in a Mexican mining town as a crowd of their friends looks on. Their children have children, who have children, their descendants still living across North America today.

* * *

What can we say that would make us understand better than we do already? Joy Harjo asks in her classic poem Anchorage. She proceeds to encapsulate in a few stanzas core themes of American Indian history: rootedness and displacement, pain and laughter, a seemingly impossible but true survival. In researching this book, I have often come back to Harjos question. What might I say that would make you understand better than you already do the history of Native people confronting colonialism? As an outsider, I will never understand what it means to be Apache in America in the way Kenoi did, and many writers have already offered powerful lenses through which we might understand stories like his. Evoking their insights, I could see Kenois history as rooted in cycles of conquest or resistance to forced colonization. I could frame his tale as a story of surviving genocide or as a story of survivance, among other possibilities. There is deep insight in all of these formulations, but there is also something not fully captured by them: the far-flung geography of Kenois life and the lives of Apaches like him.

These are lives of resistance, survival, and more, but they are also lives that map the diaspora of a people. The use of the term diaspora has expanded in recent years, and it has sometimes been employed simply as a synonym of migration in order to describe any dispersal of a people from their homeland. Scholars employing a more rigid conception have argued that diasporas are characterized by the following: migration, collective memory of an ancestral home, a continued connection to that home, a sustained group consciousness, and a sense of kinship with group members living in different places. All five of these elements are evident in Apache history, even if some characteristics have been more pronounced at certain moments than at others. Recognizing that there was (and is) an Apache diaspora helps us understand Apache and North American history better.

Diaspora is not a word in common usage among contemporary Apache communities, and for this reason I long hesitated to name what I was observing as such. Over time, however, I became convinced that I could not avoid the concept, in no small measure because Apaches so clearly expressed its significance in their stories even if they did not use the word. They told of remembering when such and such child was lost over in that country and of wanting to have all our children together where I can see them. They spoke in exile about longing to return to my land, my home, my fathers land. They repeated valiant tales of displaced Apache captives escapes and returns to kin against the odds.