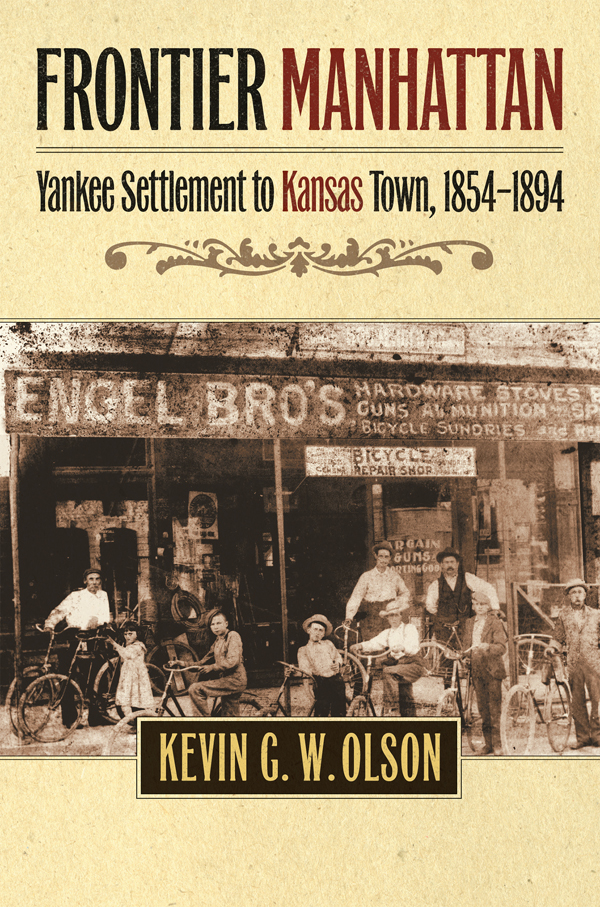

FRONTIER

MANHATTAN

YANKEE SETTLEMENT

TO KANSAS TOWN,

1854-1894

KEVIN C. W. OLSON

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

2012 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Olson, Kevin G. W.

Frontier Manhattan : yankee settlement to Kansas town, 18541894 / Kevin G. W. Olson.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-7006-1832-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2140-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2177-4 (ebook)

1. Manhattan (Kan.)History19th century. 2. Frontier and pioneer lifeKansasManhattan. I. Title.

F689.M2047 2012

978.1'28dc23

2011047229

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

TO MY PARENTS,

WITH DEEPEST LOVE AND

TREMENDOUS GRATITUDE

FOR ALL THEY HAVE DONE.

PROLOGUE

On a frosty afternoon in Kansas Territory on March 27, 1855, a stern Rhode Island abolitionist named Isaac Goodnow and five other New Englanders wrestled a bulky canvas tent into shape in a tallgrass prairie at the junction of the Kansas and Big Blue rivers. The prairie was colder than Goodnow had imagined it would be in late March. But he and his party were in good spirits as they moved mattresses and supplies from the wagon into their campsite: the men had finally reached their destination after a three-week trip from Boston, covering 1,500 miles, capped by a struggle to get their overburdened covered wagon through the snowstorms and icy rivers of Kansas Territory. Happily, the first night at the site rewarded them with a splendid moonlit evening.

Only one of the six men who found themselves on the frontier that night was familiar with the conditions. Massachusetts native Luke Lincoln had been to Kansas Territory the summer before, when it originally opened to settlement. The others had rarely been far from New England. Goodnow was a teacher at an academy outside Providence; another, Charles Lovejoy, was a noted preacher from New Hampshire; and a third was Lovejoys seventeen-year-old son. Yet all were bound and determined to transplant antislavery ideals to the unbroken soils of Kansas Territory.

They were not the first pioneers seeking to settle this site. In fact, a shrewd land speculator had already built a log cabin nearby. But they were the vanguard of a larger group of New Englanders who would transform the spot from open prairie into a frontier settlement. Over the next few days, the six men would further reinforce the walls of their tent with sod bricks while welcoming additional Yankees to their camp. The men would also come face-to-face with a band of fifteen mounted and armed Southerners who made bombastic threats, slashed their tents ropes, and fired a musket ball through the tent in an effort to scare away the abolitionists.

For many New Englanders who ventured to Goodnows camp that spring the challenges were too much to bear. Desolation, harassment, and homesickness conspired to drive them back east to the United States. But Goodnow was resolute he was a hard worker who adopted the creed we should die with the harness on and he held his ground to establish an antislavery and educational stronghold on the site: the town of Manhattan, Kansas. It was not an easy task.

THE PEOPLE, THE PLACE, THE TIMES

In the spring of 1855 Manhattan was founded as an ardent, fire-eating antislavery settlement on the Kansas Territory frontier. The founding of Manhattan was part of the rapid westward expansion of the United States. Less than eighty years had passed since English colonists, clinging to the East Coast, issued a Declaration of Independence from the British king.

In the turbulent era when Manhattan was established five and a half years before Kansas became a state Kansas Territory was sparsely populated with Native Americans, woolly frontiersmen, overwhelmed settler families in covered wagons, and fanatics of all stripes, including Yankee abolitionists, southern proslavery reactionaries, and religious missionaries seeking to convert Native Americans. It was not yet the time of saloons and cowboys, though they were coming soon. And although the United States was on the cusp of a new age of travel and communication, Manhattan was founded during a simpler, slower era. As the author Henry Adams later observed, in essentials like religion, ethics, philosophy; in history, literature, art; in the concepts of all science, except perhaps mathematics, the American boy of 1854 stood nearer the year 1 than to the year 1900. (An illustration of the primitiveness of the era is that the tallest building in the world in 1855 was the Strasbourg Cathedral, built by medieval men.)

The Pony Express, the transcontinental telegraph, and the transcontinental railroad were marvels of speed that still lay in the future when Manhattan was founded. In 1855 it regularly took travelers and news reports, traveling overland at a normal rate, five days to make the long journey of 125 miles from Manhattan to Kansas City the nearest village with a population over 1,000.

Manhattan itself was barely more than a small, remote camp for the first years of its existence. But most of Manhattans settlers arrived in this faraway place resolved to outlast any inconvenience or danger. The founders of Manhattan were abolitionist New Englanders and other Free-Staters, who raced to Kansas Territory to cast a vote for antislavery candidates for the Territorial Legislature a vote that would help determine whether Kansas entered the Union as a free state or a slave state and who stood firm afterward in the face of widespread proslavery violence. The founders were a zealous, self-selected group of people who risked their personal safety and left behind civilization and family, all to help curb the spread of slavery.

To fully understand the settlers who went to Kansas Territory, it is important to recognize that while all the Free-Staters in Kansas opposed the introduction of slavery into the territory, only some were abolitionists. Others insisted they wanted the territory to be free of all African Americans whether enslaved or free. The editor of the Manhattan Express clearly expressed the Free-State line in an editorial on June 30, 1860: We oppose slavery in the territories, not for love of the negro but the white man, whom we would save from the condition, either as an arrogant slave holder, or as degraded by him, in which we find him in the slave states. Nor do we want the free blacks, for, degraded as they are, they constitute a pernicious element, like other unfortunate subjects of society.

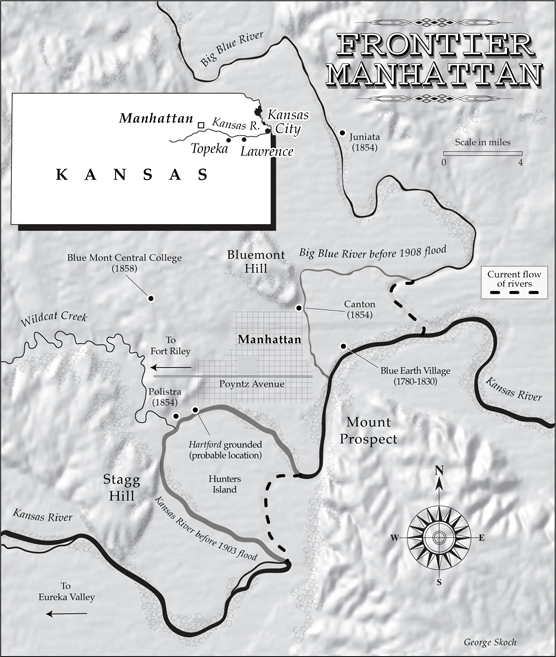

Map by George Skoch.

Map by George Skoch.