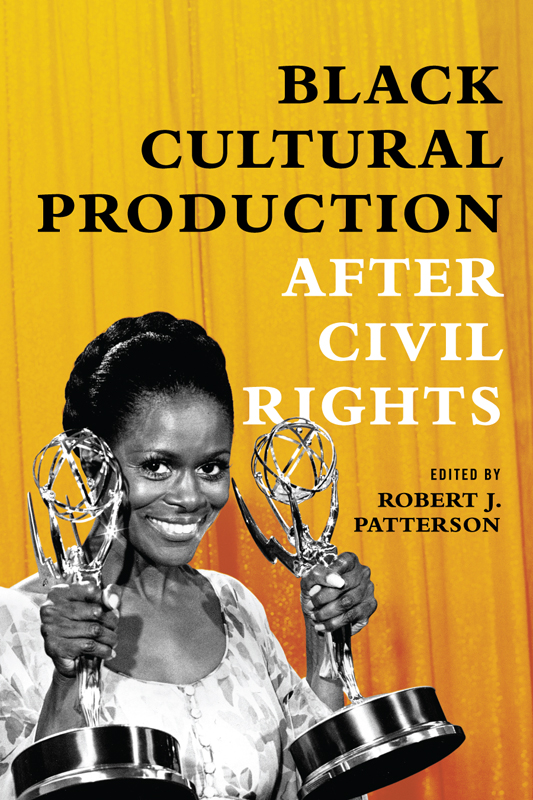

Black Cultural Production

after Civil Rights

Black Cultural Production

after Civil Rights

Edited by Robert J. Patterson

2019 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Patterson, Robert J., [Date] editor.

Title: Black cultural production after civil rights / edited by Robert J. Patterson.

Description: [Urbana, Ill.]: [University of Illinois Press], [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019007394 (print) | LCCN 2019013708 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252051630 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252042775 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252084607 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : African American arts20th century. | African American artsPolitical aspectsHistory20th century. | American literatureAfrican American authorsHistory and criticism. | African Americans in motion pictures. | African American artists. | African AmericansIntellectual life20th century. | Politics and cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC NX 512.3. A 35 (ebook) | LCC NX 512.3. A 35 B 596 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/960730904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019007394

Black Lives Matter

Contents

Robert J. Patterson

Madhu Dubey

Lisa Woolfork

Monica White Ndounou

Courtney R. Baker

Nadine M. Knight

Samantha Pinto

Jermaine Singleton

Terrion L. Williamson

Kinohi Nishikawa

Soyica Diggs Colbert

Robert J. Patterson

Acknowledgments

Black Cultural Production after Civil Rights brings together a range of scholars whose vast expertise, conscientiousness, and research made this volume possible. Within African American Studies, edited volumes have played an indispensable role in disseminating knowledge, cultivating interdisciplinary modes of inquiry and methods of analysis, and advancing the missions of Black Studies. The commitment of Madhu, Lisa, Monica, Courtney, Nadine, Samantha, Jermaine, Terrion, Kinohi, and Soyica made it possible for us to advance and add to important arguments, perspectives, and voices to the field. I appreciate the care with which they all approached their individual essays, as well as the seriousness with which they engaged each others chapters. The explicit interchapter conversations undoubtedly have enriched the volumes intertextuality. I welcome the opportunity to work with them on future projects.

A range of cultural modes of expressivity find themselves in this volume, and their very existence also made the examinations that Black Cultural Production undertakes possible. While I will not attempt to name every artist and artistic production this volume analyzes, I will offer sincere gratitude to the artistic production and artists alike. This volume centralizes artistic production from the 1970s and accentuates how it helps us to better understand black freedom dreams, black freedom movements, and black freedom strategies. That we continue to think about, write about, and dream about the significance of this historical period attests to our deep appreciation for the work it has done, continues to do, and will do.

For the past three years, my research assistant, Sebastien Pierre-Louis, has provided a variety of support on different projects. For Black Cultural Production , Sebastien once again contributed essential assistance that facilitated the completion of this project. Each chapter appreciates his attention to detail. As an undergraduate in the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University, Sebastien probably knows more now about the Chicago Manual of Style than he cares to know! Nonetheless, I appreciate his thoroughness and commitment to this project. I also thank the Department of African American Studies for the support it provided. Finally, I appreciate the Competitive Grant-in-Aid that Georgetown Universitys Main Campus Research committee awarded this project to aid in its publication.

The editorial staff at the University of Illinois Press continues to expand its list in African American Studies, and I thank Dawn Durante for her leadership in and commitment to this effort. Since Dawn and I first discussed this volume, she has remained enthusiastic, engaged, insightful, and unwavering. I value the feedback she provided for the chapters; along with that of the two anonymous readers, her suggestions enhanced the books execution. Many thanks, too, to Alison Syring, an editorial assistant whose conscientiousness and efficiency ensured the successful production of this project.

This volume reminds us that the whole remains greater than the sum of its parts. Community matters, as does black life. Black Cultural Production evidences both, and for that fact I express gratitude.

INTRODUCTION

Dreams Reimagined

Political Possibilities and the

Black Cultural Imagination

ROBERT J. PATTERSON

The 1970s Contextualized

When DuBois identified the problem of the twentieth century as the color line, the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea, at the turn of the twentieth century, he hardly could have imagined then that his declaration would hold true during the second decade of the twenty-first century. Although DuBois would later question the United States commitments toward democracy and equality, and ultimately renounce his U.S. citizenship, his death in 1961 preceded the pinnacle legislative achievements of the modern civil rights movement. Had Du-Bois, for example, witnessed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he might have reconsidered the possibilities for racial equality as approaching and imagined the ebbing of the color line. Even if he had lived through the 1960s, his enthusiasm would have lived ephemerally as his previous disillusionment became more entrenched. Indeed, the 1953 Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas ruling had overturned legal segregation, second-class citizenship, and the white supremacist enhancing policies and laws that the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling had authorized, codified, and reinforced. It paved the way for the civil rights acts of the 1960s. Yet, the 1970s ushered in an anticivil rights backlash that, when coupled with an increasing tide of conservatism, impeded the enforcement of civil rights legislation.

The postcivil rights era retrenchment of de facto segregation revealed how white supremacy and antiblack racism were interconnected, intertwined, interrelated, and deeply embedded in Americas values and institutions. Neither legislative acts nor a naive belief in the general goodness of the American people could undo their historical and emotional sentience.

Postcivil rights era assaults on legal remedies to black inequality thus all but ensured the limited development of sustainable institutional and infrastructural changes to translate so-called equal opportunities into equal outcomes . Black people theoretically had the same access as whites to previously denied opportunities, yet black peoples previous exclusion diminished the degree to which taking advantage of the new opportunities would equalize their chances for equality; the juridical changes alone could not account for the cumulative effects the historical disadvantages had produced. This disparity, rooted in the legacies of historical discrimination and compounded by new manifestations of Jim Crow and its legacies, perpetuates the material disparities between white and black people in the postcivil rights era. While Michelle Alexander rightfully notes how mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex extend Jim Crows reach, the new Jim Crow possesses many additional manifestations, too, in the postcivil rights era.