First published in Great Britain 1986 by Leo Cooper

This edition published privately by the author 1993

in cooperation with Leo Cooper Ltd

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire

Copyright 1986, 1992 S. Shahid Hamid

ISBN 0-85052-396-6

Printed in Great Britain by

Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Plates printed by BAS Printers

Over Wallop, Hampshire

This second edition of Disastrous Twilight is important for two main reasons. Firstly, many people who were deeply interested in the whole subject of Partition in India, in the events that led up to it, the process of Partition itself and the very controversial issue of the boundary awards, as well as the appalling aftermath of Partition, were unable to obtain copies of Shahid Hamids book. Their needs must now be met and it is also necessary to consider the strong reactions to the book both in literary reviews and in letters, debates and broadcasts after its publication in 1986.

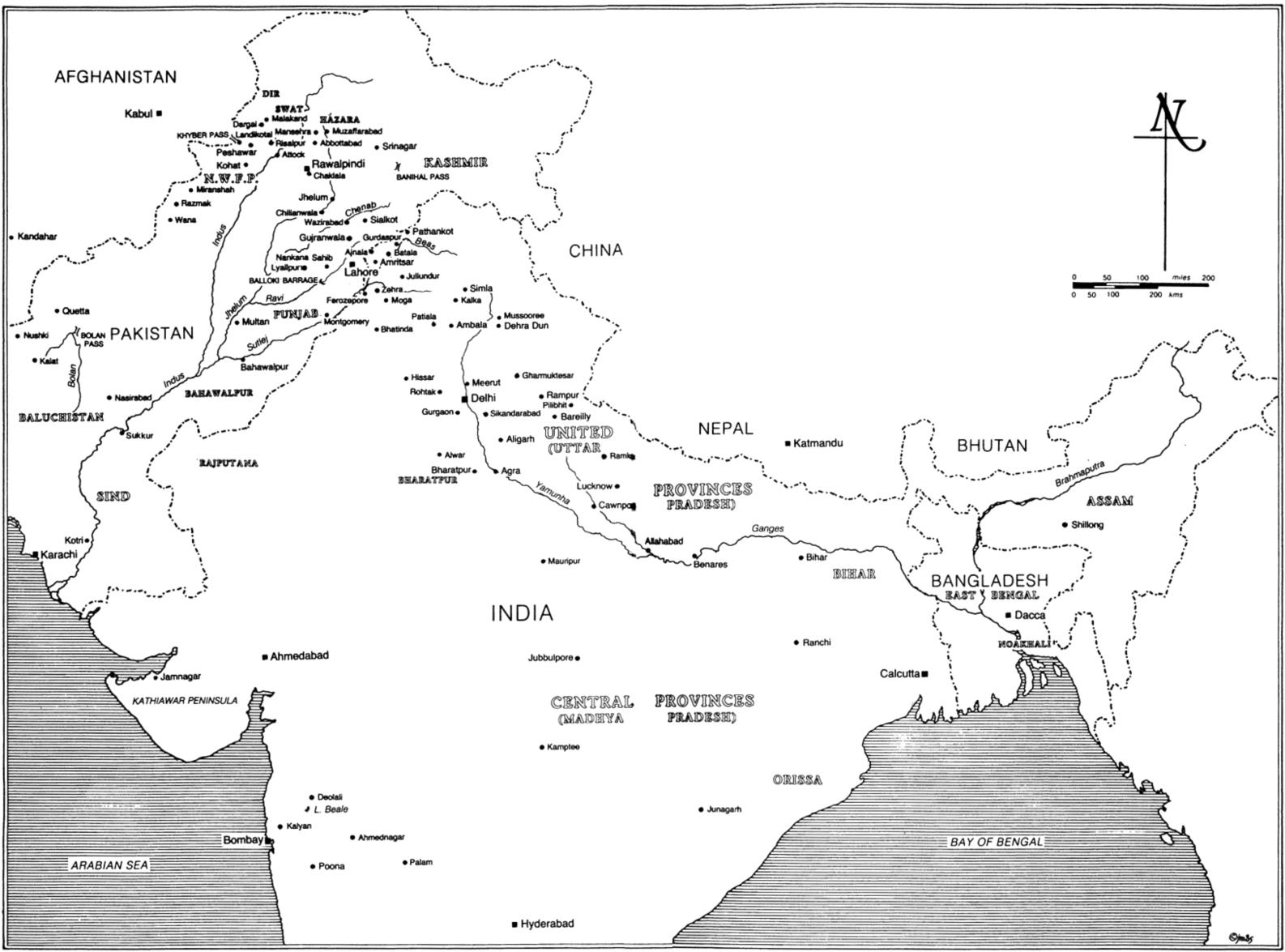

Secondly, important new evidence has come to light recently about the Boundary Award following disclosures made by Christopher Beaumont, who was secretary to Sir Cyril Radcliffe, Chairman of the Boundary Commission between India and Pakistan. After the death in 1989 of Sir George Abell, who was private secretary to Lord Mountbatten as Viceroy, Christopher Beaumont is now the only person alive who can personally testify about the reasons for the decisions behind the Award and the modifications those decisions underwent. His disclosures cast considerable doubt on the impartiality, and indeed the integrity of the last Viceroy of India at that period, and must therefore be examined carefully. It is an inevitable consequence, too, that Philip Zieglers judgements, both as the official biographer of Lord Mountbatten and as the author of the foreword to the original edition of Disastrous Twilight, must also be called into question.

I have known Shahid Hamid for a very long time and have been closely associated with him in some of the books he has written. I think, therefore, that I am able to make personal judgements about him and his work with due impartiality. I also had the privilege of knowing the Auk quite well after he had retired as Commander-in-Chief, India, and will not conceal my admiration for that great man.

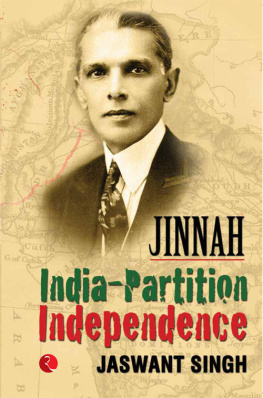

Let us start by examining the reviews and comments which were made after the publication of Disastrous Twilight. It is clear that the events in India during 1946 and 1947 still arouse intense passions among many people in the U.K. and others overseas. These views are not confined to the older generation who lived through those momentous times, but have percolated down to their children and even their grandchildren. When lecturing on India to adult audiences for Bristol University I have found them especially interested in the period of the British Raj and its eventual break-up, a subject which always produces lively discussion because so many British families have had connections of some sort with India. The discussions turn quickly to personalities, involving particularly General Wavell, still very much loved in the U.K., the Auk and Mountbatten on the British side, and Nehru and Jinnah on the Indian.

This clash of personalities dominated, too, the debate and the reviews after Disastrous Twilight had appeared. In his article A Biased General John Grigg of The Daily Telegraph wrote that Shahid Hamid was a partisan of Muslim separatism so blinded by prejudice that he can seldom see any good in a Congress leader, while apparently he sees no defects at all in his hero, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Grigg concluded by accusing Hamid of being a committed Muslim Leaguer who clearly acted as a spy for Jinnah, with possibly disastrous consequences an astonishing assertion to which Shahid Hamid gave a dignified denial in a letter to the same paper. The comments of John Keegan of The Daily Telegraph, however, were far more perspicacious. After stating that Hamid had a mind of the first class, allied to personal qualities quite as outstanding, he continued, But politics are not the real fascination of this book. Personality predominates. General Hamid is a sort of Indian Saint-Simon. He has an eye quite as keen as that of the Pepys of Versailles for the vanities, egotism, ambition, spitefulness, petty self-advancement and surreptitious doing-down of rivals that characterize any court.

Although John Keegan is quite right in what he says it is a sad reflection that Vice-Regal Lodge should have become at this time as it undoubtedly did a hotbed of intrigue and ambition. Did Mountbatten, one is tempted to ask, regard himself as a sort of 20th century Moghul emperor? There is some evidence that he did. The one towering unshakeable character in the midst of these storms and tempests was Auchinleck a fact acknowledged by almost all the reviewers, especially John Biggs-Davidson in his article Calendar of Chaos in The Spectator and the reviewer of Disastrous Twilight in the British Army Review. The latter writer commented that the political scene was so tortuous and the atrocities committed against the Muslim peoples were so horrific, that there were times when the reader was driven to feel that the whole story was like some daemonic and nightmarish version from Alice in Wonderland. He could well have added Franz Kafka.

It is against this background that the officers of the Indian Army stand out so superbly in their desperate attempt to maintain their standards of total impartiality. They had been devoted to Wavell, who was so disgracefully treated by the British government, as Shahid Hamid describes in this book, and above all to the Auk. Hamid reminds us that Churchill wrote of him: The Auk was an officer of the greatest distinction and a character of singular elevation the greatest general of the war. The author of the article in the British Army Review sums up quite brilliantly the essential issue when he writes This (book) is a story of stark tragedy and of utterly disgraceful behaviour a dark bitter pool of reminiscence from the depths of which few characters of real integrity stand out like beacons, the brightest of which, need one say, being that great and much-wronged figure the Auk.

Integrity surely that is the highest accolade which history can accord, for it also implies a correct judgement and an absence of personal ambition. In this book Hamid arraigns before the bar of history the representatives who were chiefly responsible for the terrible mistakes and events of the period the Auk, Mountbatten, Nehru and Jinnah and those who served under them. There is no doubt that in his opinion the Auk and Jinnah pass the test of integrity : Mountbatten and Nehru do not.