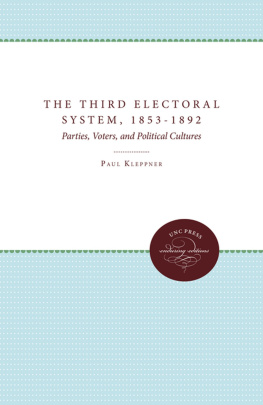

FROM FARMYARD TO CITY SQUARE? THE ELECTORAL ADAPTATION OF THE NORDIC AGRARIAN PARTIES

From Farmyard to City Square? The Electoral Adaptation of the Nordic Agrarian Parties

Edited by

David Arter

Nordic Policy Studies Centre

University of Aberdeen

First published 2001 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright David Arter 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

From farmyard to city square?: the electoral adaptation of

the Nordic agrarian parties

1.Political parties - Scandinavia 2.Scandinavia - Politics

and government - 1945

I.Arter, David, 1944

324.2'48'087

Library of Congress Control Number: 2001089131

ISBN 13:978-0-7546-2084-6 (hbk)

Jrgen Goul Andersen is Professor of Political Sociology in the Department of Economics, Politics and Public Administration at the University of Aalborg. In recent years he has written widely on voting behaviour and political attitudes in Denmark, along with the challenges facing the welfare state. His research interests include electoral behaviour, political participation and citizenship.

David Arter is Professor of Nordic Politics and Director of the Nordic Policy Studies Centre at the University of Aberdeen. He has written extensively on various aspects of Scandinavian and European politics. His recent published research has examined the regionalisation process in Northern Europe, perceptions of parliamentary change in the region and a study of the Finnish Committee for the Future.

Dag Arne Christensen presently holds a post in the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development in Oslo. His doctoral thesis from the University of Bergen, published in 1998, analyses the EU policies of the left-socialist parties in Scandinavia. He has published several comparative articles on Scandinavian party politics

Jan Bendix Jensen completed his undergraduate studies in the Department of Politics at the University of Aarhus and is presently engaged in doctoral research at the University of Aalborg. His main interests lie in the fields of electoral studies and the welfare state in comparative perspective.

Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson is Professor of Government at the University of Iceland. He completed his doctoral thesis at the University of Essex on the farmers' parties of Iceland, Norway and Sweden. He has published on many facets of Icelandic politics, particularly in the area of public administration. He is presently undertaking a study of local government performance in Iceland.

Anders Widfeldt gained his doctorate in 1997 from the University of Gteborg for a thesis examining party membership in Sweden since 1960. He is presently lecturer in Nordic politics at the University of Aberdeen. His recent published work has dealt with the representativeness of Swedish parties, the populist Right in Scandinavia and the public funding of political parties.

In his path-breaking work on the catchall 'people's party' in the mid-1960s, Otto Kirchheimer made it clear that because of their defence of a specific clientele, agrarian parties could not become catchall parties. But could the distinctive family of Agrarian Parties in Sweden, Norway and Finland, redesignated Centre Parties in the 1950s and 1960s, be expected to do any better? And what of those parties Venstre in Denmark and the Progressive Party in Iceland that emerged primarily to promote agricultural interests, even if they were not class parties by name? Accordingly, the basic research question in this volume is: 'How successful have the Nordic agrarian parties been in their attempt to transform themselves from class parties to broad catchall parties drawing significant support from voters engaged in the non-primary sectors of the economy?' The study therefore focuses on electoral adaptation that is, the redefinition of party identity and institutional modernisation that is, the development of new policies, programmes and strategies. It aims to provide a detailed profile presently not available in any language of an historic group of parties, with distinctive strength in the Nordic region, as well as to attempt an assessment of the process of party change. Edited volumes have covered social democratic parties (extensively), liberal parties and conservative parties but, curiously, not agrarian-centre parties. It is hoped that the present collection will remedy this omission and provide a text of interest to Scandinavians, comparativists more generally, as well as the increasing body of scholars specialising in political parties.

The individual chapters, covering the agrarian parties in all five Nordic states, are structured in four main parts. The first focuses on the process of the emergence of the parties. There is an examination of the political and socio-economic conditions at the time of their inception, the particular party's links, if any, with agricultural producers' organisations, the nature and regional distribution of its support base (whether based on independent family-sized farms, larger farmers, crofters etc) and fluctuations in its support. How relevant was the Lipset and Rokkan model for the emergence of strong agrarian parties to the particular country in question? Moreover, did the individual party advocate measures of agricultural protection or free trade? Then there is the interesting issue of persistence. Indeed, it might be argued that it was not so much the emergence of farm-specific parties in the Nordic region that was distinctive peasant parties arose across central and eastern Europe in the period before and after the first world war. Rather, it was the fact that they persisted until the late 1950s in Sweden and Norway and until 1965 in Finland, Why? (Agrarian-peasant parties have re-emerged across post-communist Europe, inter alia in Poland, Hungary and Croatia, but that is another story.) In this first section there is also a discussion of the 'relevance' (in Sartori's terms) of the farmers' parties their involvement in government and in strategic legislative coalitions. Finally, there is an assessment of the role of agrarian parties in relation to such key issues as state-building, land reform, welfare development, constitutional change and, of course, war.

The second section in each chapter involves a detailed analysis of the process of programmatic renewal and/or change of name (Denmark emerges as a deviant case). What were the root causes of modernisation and when did it happen? In the Finnish case, for example, the change of name was first mooted in 1950, but took a decade and a half, and a change in the leadership, to be realised. What was the time-scale elsewhere and to what extent did accelerated industrialisation, urbanisation and rural depopulation prompt an internal party debate about a suitable response? Was there unanimity on the way forward or did modernisation divide the party? Who were the personalities on both sides of the argument? And what were the objectives it was hoped would be achieved?