Black Lives and Bathrooms

Breaking Boundaries

Series Editor: J. E. Sumerau, University of Tampa

Breaking Boundaries is meant to expand the horizons of mainstream and academic understandings of sex, gender, and sexualities. While the last few decades have witnessed increased attention to some areas of sex, gender, and sexualities, mainstream and academic focus has been generally limited to focus on cissex males and females, cisgender women and men, monosexual gay/lesbian/straight, and monogamous individuals, groups, and experiences. Building on the groundwork laid by these traditions, Breaking Boundaries focuses on other arenas of sex, gender, and sexual identities, practices, relationships, experiences, and inequalities too often missing from existing mainstream and academic discussions of sex, gender, and sexualities.

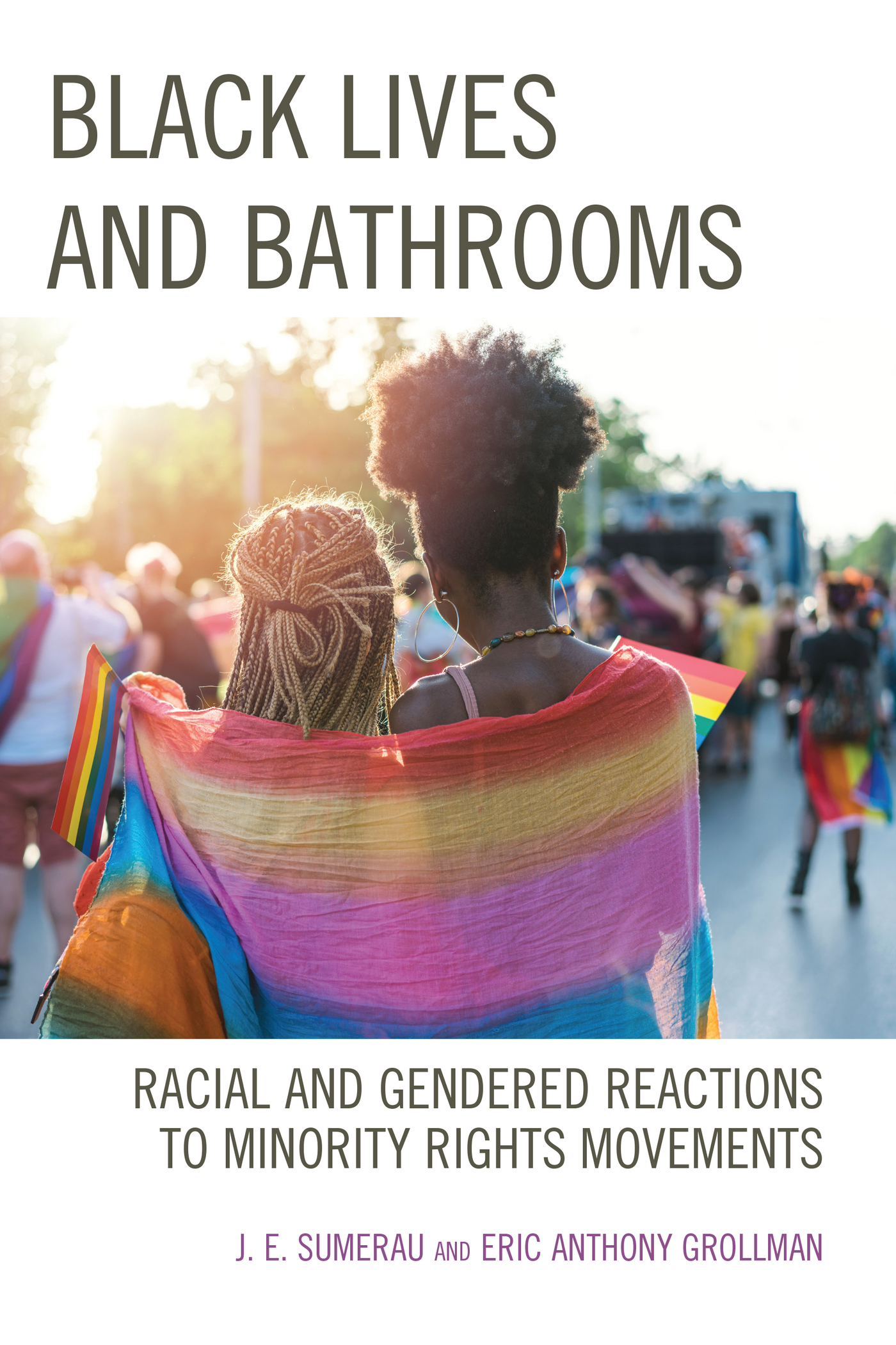

Black Lives and Bathrooms: Racial and Gendered Reactions to Minority Rights Movements, by J.E. Sumerau and Eric Anthony Grollman

Trans Men in the South, by Baker A. Rogers

Christianity and the Limits of Minority Acceptance in America: God Loves (Almost) Everyone, by J.E. Sumerau and Ryan T. Cragun

Black Lives and Bathrooms

Racial and Gendered Reactions to

Minority Rights Movements

J. E. Sumerau and

Eric Anthony Grollman

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom

Copyright 2020 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-7936-0980-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-7936-0981-6 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Introduction

Shawna was a teenager living in Sanford, Florida when Trayvon Martin was killed by George Zimmerman in the same city in 2012. As she explained to a group of other students on a college campus in the spring of 2018, news of the murder, Swept through the schools and neighborhoods, and I remember feeling even more conscious of my blackness and what that could mean to other people. An African-American, bisexual, cisgender woman in her early twenties now, Shawna completed high school and came to college interested in learning about Black history and engaging online and at events with Black Lives Matter movement efforts. As she put it on that spring day in conversation with other students, I never met Trayvon, but I recognized what happened to him on a deep level that called me to do something.

In another part of the country, Luca was starting their early twenties in 2012 when they began identifying as a nonbinary transgender person, presenting themselves in an androgynous fashion at a small college in the Midwest, and beginning medical procedures to adjust aspects of their body that, as they put it, Never fit right. As Luca explained over drinks at a tea shop in Chicago in the summer of 2018, Those early days when I was kind of in transition physically and with my appearance taught me a lot about bathroom politics. I dont think I ever really understood how hard it could be to just go to the bathroom if you did not fit into the segregated ideas of men or women only. As a white, queer, nonbinary transgender person, Luca has worked in the years since with groups seeking to obtain bathroom access for transgender people of all types and educate cisgender others on transgender experience. As they put it after a small sip of tea on that summer afternoon, I just felt like it was never going to get any better if I didnt do something, and I found others who felt the same way.

While Shawna and Luca represent people invested in two major social movements taking place at the same time in the contemporary United States, Sandy lives her life at the intersection of both of these movements. As an African-American, heterosexual, transgender woman living in the northeast, Sandy navigates a social context where, as she put it sitting on a bench in an urban area on a break from work in the summer of 2018, Both Black and trans people are under attack, or at least it feels that way, every day. Like many people, Sandy spends much of her spare time working online and within groups seeking community action and solutions for these issues while navigating work and personal spaces in real life where these issues feel omnirelevant. As she put it on that summer afternoon, You got to do whatever you can to get by because what else can you do. I mean, it just feels like youre not really okay anywhere, either white or cis supremacy, or both, are going to come around no matter where youre at.

Each of these stories reflect a common thread in much social movements scholarship (Reger et al. 2008; Rohlinger 2006; Schrock et al. 2004; Ray et al. 2017). Put simply, researchers have often examined the ways people become active in social movements in relation to their own social locations within systems of race, sex, class, gender, sexuality, religion, and other identities (see also Almeida and Chase-Dunn 2018; Amenta and Polletta 2019; Wang, Piazza, and Soule 2018). Further, researchers have often focused on the ways people in social movements narrate their introduction to and participation within such movements over time. In fact, researchers have noted how the combination of individual and collective identities often forms the basis and foundation for movement activity, cohesion, commitment, and overall participation (Polletta and Jasper 2001). While such literature, as well as the stories shared above, has dramatically expanded our understandings of social movements and the ways people become active within them in different ways, researchers have spent much less time examining the ways people who are not affiliated with a given movement respond to such endeavors (see also Mathers et al. 2018; Sumerau and Cragun 2018; Sumerau et al. 2017).

As we have noted elsewhere (Sumerau and Grollman 2018), this pattern mirrors broader social scientific scholarship wherein researchers typically focus on the members of groups marginalized by a given system of inequality (see also McDermott and Sampson 2005; Schrock and Schwalbe 2009; Schwalbe et al. 2000). When scholars focus on race or racial movements, for example, such work is more likely to focus on Black people and other people of color harmed by racism and seeking to challenge white supremacy rather than on the white people who benefit from the system (Bonilla-Silva 2018). Likewise, when scholars focus on sexualities, such work much more often focuses on the experiences and movement efforts of sexual minorities than the ways heterosexuals respond to and benefit from systems of heterosexual privilege or react to such movements (Schrock et al. 2014). Recognizing these patterns, scholars including but not limited to those cited above have emphasized the importance of flipping this script to examine how people who benefit from an existing system of inequality respond to attempts to shift or change such systems in various ways (Collins 2005 and 2015).

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.