First published 2000 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Lorna Chessum 2000

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Chessum, Lorna

From immigrants to ethnic minority : making black community in Britain. - (Interdisciplinary research series in ethnic, gender and class relations)

1. Blacks - England - Leicester - History - 20th century

2. Immigrants - England - Leicester - History - 20th century

3. West Indians - England - Leicester - Social conditions

4. Leicester (England) - Race relations

I. Title

305.8969729042542

Library of Congress Control Number: 00-133523

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-1019-9 (hbk)

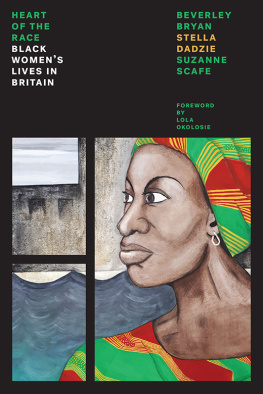

From Immigrants to Ethnic Minority is a peculiar story of people who descended from Africa but who live in societies structured in dominance. Other immigrants have since become citizens but people of African descent are condemned to the inferior status of ethnic minority on the basis of their gendered, class-specific racialisation. Although Dr Lorna Chessum focused on the African Caribbean Diaspora in Leicester and excluded African immigrants for the sake of her doctoral requirement to narrow the focus of her analysis, what she says about her subjects is applicable to the worldwide African Diaspora even in South and North America where hundreds of millions of people of African descent remain ethnic minorities while recent immigrants are already perceived as full citizens due to their Euro-Asian origins and relative affluence.

The author combines limited primary archival sources with abundant oral history and secondary sources to analyse public policy and national or local debates concerning the presence of large groups of black people in the East Midlands city of Leicester since the end of the Second World War - the largest such population outside London. The book demonstrates that just like all people of African descent in racist and sexist capitalist societies, the black people who were lured to Leicester with promises of abundant jobs arrived with immense skills and enthusiasm only to be marginalised into racialised and gendered menial jobs instead of being allowed equal opportunities. Although this could be said to be the experience of most immigrant groups, the persistence of racism, class-snubbery and sexism has meant that black men and black women have largely remained in their marginalised positions more than fifty years after the first generation was begged to come and serve the war-weakened mother country while other richer or whiter groups of immigrants have fared better.

The book charts the amazing survival of black people in an incredibly hostile environment that has not stopped discriminating against them. In that sense, being regarded as ethnic minorities is a grudging acceptance that, as Linton Kwesi Johnson put it, No matter what they say, come what may, we are here to stay ina Ingland. Compared to another group of racialised immigrants also regarded as part of the ethnic minority population of Leicester, the author found that the Asians (mostly middle class refugees from East Africa) were racialised on a higher hierarchy due to their relative access to economic and political power and their consequent access to the different classes of the British population whereas the African Caribbeans remain impoverished as working class and unemployed elements of the ethnic minority.

The major conclusion readers can draw from this book is that the marginalisation of the African Caribbean in Britain should be understood within the context of institutionalised racism-sexism-classism instead of being blamed on the attitudes of individuals alone. The book reveals that the national and the local governments were active in constructing the third-class status of the African Caribbean as an ethnic minority when policy attempts to restrict the growth of multicultural Britain was successfully resisted by the initial black immigrants and their descendants. Since the government played active roles in restricting the growth of the opportunities and numbers of African Caribbeans in Britain, the government should also be responsible for rehabilitating the descendants of the initial immigrants who were exploited and maltreated for so long in spite of their eagerness to help the mother country back on its feet after the war.

Dr Biko Agozino