Eastern

Africa

Series

GENDER,

HOME

& IDENTITY

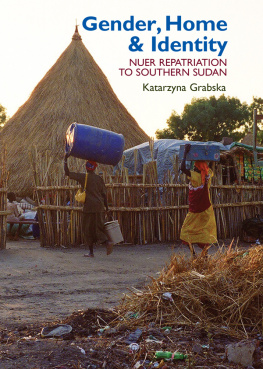

During the civil wars in southern Sudan (1983-2005) many Sudanese, including many Nuer, were in refugee camps in Kenya and Ethiopia, repatriating to southern Sudan only after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. This book follows the lives of a group of Nuer who escaped the wars, and then returned to try to recreate a sense of home, community and nation. Conceptualising conflict-induced displacement as a catalyst of social change, this book explores the transformation of gender and generational relations among southern Sudanese Nuer in the aftermath of the war and the complexity of social change in the context of forced displacement and state formation in what is now South Sudan.

Eastern

Africa

Series

Womens Land Rights & Privatization in Eastern Africa

BIRGIT ENGLERT & ELIZABETH DALEY (EDS)

War & the Politics of Identity in Ethiopia KJETIL TRONVOLL

Moving People in Ethiopia

ALULA PANKHURST & FRANOIS PIGUET (EDS)

Living Terraces in Ethiopia ELIZABETH E.WATSON

Eritrea GAIM KIBREAB

Borders & Borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa

DEREJE FEYISSA & MARKUS VIRGIL HOEHNE (EDS)

After the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in Sudan

ELKE GRAWERT (ED.)

Land, Governance, Conflict & the Nuba of Sudan

GUMA KUNDA KOMEY

Ethiopia JOHN MARKAKIS

Resurrecting Cannibals HEIKE BEHREND

Pastoralism & Politics in Northern Kenya & Southern Ethiopia

GNTHER SCHLEE & ABDULLAHI A. SHONGOLO

Islam & Ethnicity in Northern Kenya & Southern Ethiopia

GNTHER SCHLEE with ABDULLAHI A. SHONGOLO

Foundations of an African Civilisation DAVID W. PHILLIPSON

Regional Integration, Identity & Citizenship in the Greater Horn of Africa

KIDANE MENGISTEAB & REDIE BEREKETEAB (EDS)

Dealing with the Government in South Sudan CHERRY LEONARDI

The Quest for Socialist Utopia BAHRU ZEWDE

Disrupting Territories

JRG GERTEL, RICHARD ROTTENBURG & SANDRA CALKINS (EDS)

The African Garrison State

KJETIL TRONVOLL & DANIEL R. MEKONNEN

The State of Post-conflict Reconstruction

NASEEM BADIEY

Gender, Home & Identity: Nuer Repatriation to Southern Sudan

KATARZYNA GRABSKA

Remaking Mutirikwi*

JOOST FONTEIN

* forthcoming

Contents

Maps and Photographs

Maps

Photographs

Preface

The stories of lives fragmented by wars, experienced in several contexts and pieced together in the aftermath are seldom told. This book follows the efforts of seventeen Nuer families and over fifty additional individuals who fled their homes due to the violence and wars that tore their communities apart, were displaced throughout Sudan and East Africa and eventually settled in a refugee camp in Kenya. In the process, their lives were irreversibly changed, and in unexpected and differentiated ways. Many years later, in the aftermath of repatriation, they and their relatives and friends who were displaced elsewhere, or who had stayed behind, have come together to (re)create and (re)build a home, a community and a nation. The narratives of those displaced and those who had stayed behind reveal the complexity of social change in the context of forced displacement and nation-building.

Since the mid-1990s, I have been following the developments in Sudan and consequently in South Sudan, first during my MA studies, later as a researcher of Sudanese refugees livelihoods in Cairo and subsequently as a doctoral student between 2005 and 2010. Based mainly on multi-sited ethnographic research in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya and in South Sudan between April 2006 and September 2007, which formed the fieldwork for my DPhil in Development Studies, this book narrates and analyses the experience of gendered and generational displacement of the group of Nuer women and men whom I followed.

In , I explain in more detail the methodology on which the fieldwork was based as well as the choice of interviewees. The three main characters whose narratives constitute the backbone of the story line in the book were chosen deliberately. I became very familiar with the lives of these three individuals and their families throughout my research, meeting them first in Kakuma and then throughout my time in South Sudan. I have also kept in touch with them since 2006. I felt that their individual stories presented a set of diverse experiences of single mothers, young women and men who were the main groups of refugees I encountered in Cairo or in Kakuma. My respondents insisted that I refer to them using their real names as they wanted their experiences to be shared with others. To honour them, I have kept parts of their names unchanged while not providing them in full to protect their identity to some extent.

The research for this book took place mainly before South Sudans independence. I use the term southern Sudan to refer to the area of Sudan before the Souths 2011 independence. To reflect the fragile situation of post-war southern Sudan, I use the term after-fire fieldwork. This term refers to the book Fieldwork Under Fire which discusses ethnographic fieldwork in the context of war and violence. My after-fire fieldwork was carried out in the wake of decades of conflict in southern Sudan.

In this preface, I set out a few explanations for the readers related to the use of names, transliteration, and the use of language in the citation. The spelling of the primary location of my research in South Sudan is often confusing and is used in a variety of ways. Lr is the transliteration from the Nuer. Ler is the English version of the term. Leer is NGO-speak, a transcription of the way Lr is written in Arabic where it appears either with a long vowel (Leer) or a diphthong (Lair). I follow the Nuer original transliteration and use Lr throughout the book.

The informants sometimes spoke in Nuer and sometimes in English, and at times Dinka or Arabic. Sometimes they also mixed words from one language into conversation in the other. I have thus standardised the use of the two main languages for quotes. I use English with significant words only in Nuer in brackets. I use square brackets for any of my own interpolations in quoted passages. Some English terms have been adopted as loan words in Nuer. These words are placed within single quotation marks in the translation. Conversely, if the respondents were speaking in English and used a Nuer word, that word is also marked by quotation marks.

Carolyn Nordstrom and Antonius C. G. M. Robben, eds, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley, 1995).

Acknowledgements

A long journey of new discoveries, adventures, new encounters, frustrations, hardship and new friendships have accompanied the creation of this book. I would not have been able to embark on this project, let alone to complete it, without the wonderful support of so many dedicated individuals and institutions. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude goes to my two dedicated DPhil supervisors, Professor Ann Whitehead and Dr Lyla Mehta who accompanied me on this journey from its very beginning and were there for me during difficult moments of fieldwork and writing-up. They both challenged me every step of the way and encouraged me to think critically and in new ways. I have learned a lot from them thank you!

This book is also inspired by the wonderful opportunity to collaborate with Professor Barbara Harrell-Bond. Her dedication to seek justice for those who have been deprived of protection and their rights grounded my commitment to forced migration issues. She made me believe that through academic work it is possible to contribute to those whose lives have been torn apart by wars and conflicts. Thank you for believing in me.