ZUBAAN

an imprint of Kali for Women

128 B Shahpur Jat, 1 st floor

NEW DELHI 110 049

Email:

Website: www.zubaanbooks.com

First published by Zubaan 2012

Copyright individual essays with the authors 2012

This collection Zubaan 2012

All rights reserved

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eBook ISBN: 9789383074167

Print source ISBN: 9789381017210

This eBook is DRM-free.

Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi with a strong academic and general list. It was set up as an imprint of Indias first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and carries forward Kalis tradition of publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. Zubaan means tongue, voice, language, speech in Hindustani. Zubaan is a non-profit publisher, working in the areas of the humanities, social sciences, as well as in fiction, general non-fiction, and books for children and young adults under its Young Zubaan imprint.

Typeset by Recto Graphics, Delhi - 100 096

Printed at Raj Press, R-3 Inderpuri, New Delhi - 110 012

Vimala Ramachandran, Kameshwari Jandhyala and Radhika Govinda

Vimala Ramachandran

Lakshmi Krishnamurty

Kameshwari Jandhyala

Kalyani Menon-Sen

Sharada Jain and Shobhita Rajagopal

Niti Saxena and Nishi Mehrotra

Dipta Bhog and Malini Ghose

Anuradha Rajan

Revathi Narayanan

Rama V. Baru and Surekha Dhaleta

Geeta Menon and Soma Kishore Parthasarathy

Anita Gurumurthy and Srilatha Batliwala

Vimala Ramachandaran and Kameshwari Jandhyala

Where does one begin? When we toyed with the idea of a book, it was quickly evident that the process would involve discussions, dialogue and reflection and above all, that it would take time. We are grateful to Kees von Bosch and the Royal Netherlands Embassy who were convinced that the Mahila Samakhya experience is a valuable story to be told and Hanke Koopman who was a believer in the MS approach and someone who has followed its evolution since 1987, when the first concept paper was written both of them extended enthusiastic support and resources for writing the first part of the book. To Sir Dorabi Tata Trust and Ratna Mathur we are equally grateful for supporting us to complete the Mahila Samakhya mosaic.

All this would have not been possible without the unstinting sharing of materials, experience and thoughts by the whole Mahila Samakhya programme. To Vrinda Sarup (at the time Joint Secretary, Elementary Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India) and all the State Programme Directors and field teams a big thank you. It is, however, the sanghas, the womens collectives, whose commitment, conviction and struggles for gender justice were the spirit behind this endeavour.

Finally to all the contributors Sharada Jain, Shobhita Rajagopal, Kalyani Menon-Sen, Lakshmi Krishnamurty, Dipta Bhog, Malini Ghose, Geeta Menon, Soma Parthasarthy, Revathi Narayanan, Anuradha Rajan, Rama Baru, Surekha Dhaleta, Nishi Mehrotra, Niti Saxena, Anita Gurumurthy, Srilatha Batliwala and Radhika Govindawhat can we say? It was as much our story as the story of a programme. Thank you for bringing it alive.

Vimala Ramachandran

Kameshwari Jandhyala

As we were preparing to send this book to press we heard about the passing away of Mr Anil Bordia. Mr Bordia was Education Secretary to the Government of India when the idea of Mahila Samakhya was conceived, developed and launched. Indeed, it was his idea and his visionto create and launch such a programme under the aegis of the National Policy for Education (1986).

We would like to dedicate this book to him.

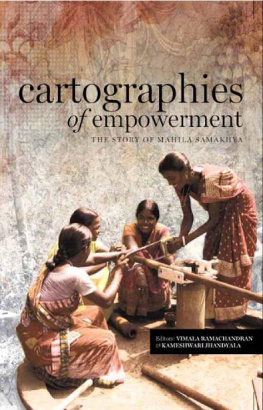

Cartographies of Empowerment:

An Introduction

VIMALA RAMACHANDRAN, KAMESHWARI JANDHYALA AND RADHIKA GOVINDA

M ahila Samakhya (MS) never fails to become the centre of discussions whenever issues of womens empowerment, the womens movement and the state, and government and civil society partnerships come up. For those of us who were associated with the programme in its earlier phases, so much in this partnership was taken for granted that even today it remains assumed rather than explicitly stated. The context that threw up this programme gave several of us our first experiences of working in civil society movements and organisations in partnership with the government. For younger colleagues who did not have a similar background the programme, its roots and its rationale were issues they became familiar with in orientation workshops and trainings. When, as authors of this essay, we began to discuss how we would write it, younger colleagues in our team asked us to explain the mid-1980s context that led to the government playing a significant role in the empowerment of women. This is what we attempt to do hereto capture the long story and biography of a programme and a movement.

The decades of the 1970s and 1980s were turbulent and heady times for social movements in India and the Mahila Samakhya (MS) story has to be seen against this context. The churning that was so evident at the time was not, interestingly, limited to civil society but could also be seen inside government programmes and in government thinking. The declaration of a State of Emergency in 1975 shook peoples faith in the abiding strength of the Indian democracy. Two years later, when Indira Gandhis Congress party was voted out of power, some of this faith was restored. Change, people felt, was possible. The 1977 elections brought in a new coalition government as an anti-Congress wave swept the country. But the euphoria was short-lived, by 1979, the cobbled-together coalition had fallen apart, and Indira Gandhi and the Congress party were voted back to power with a renewed majority. The scars and wounds of the Emergency, however, continued to fester, leading to widespread unrest in the country. As well, politics saw the rise of regional identities, and in many areas the assertion of caste and community identities led to a period of discontent and protests. This was also the time when many peoples movements sprung up across the countryagainst alcoholism, against the felling of trees (the nascent environment movement), against domestic violence and sexual harassment to name only a few. The widespread unrest on the ground was further exacerbated by the political and social fallout of the tragic events of 1984 when the assassination of Indira Gandhi led to riots and mass killing in Delhi and some neighbouring areas. The Congress party acquired a new face with the entry of Rajiv Gandhi, Indira Gandhis son, and the wave of sympathy for Indira Gandhi swept her party back into power. Under Rajiv Gandhi, began the process of the opening up of the economy and developmental discourse, policy and programmes cast in terms of meeting global standards. One of the interesting consequences of the turbulence and upheaval in Indian politics was that people began to see and acknowledge that the government was not a monolith, that it could have many faces and many internal contradictions. At some level there was also a sense that the government was answerable to the people who elected it, and that they could have a say in how it works. This renewed peoples faith in the belief that the ability to influence the government was not limited to social activists alone. Within the government, civil servants with a progressive outlook came to believe that they could also make a difference. Several worked closely with social activists and support for many of these activities came from an unexpected quarterthe media, with both print and broadcast media, particularly alternative cinema, playing an important part. It was a period that inspired and radicalised an entire generation of women, in their homes, at the workplace, in government offices, in colleges and universities and in the media.