Table of Contents

For Jordan and Maya

If there were a sympathy in choice

War, death, or sickness did lay siege to it,

Making it momentary as a sound,

Swift as a shadow, short as any dream,

Brief as the lightning in the collied night,

That, in a spleen, unfolds both heaven and earth,

And ere a man hath power to say, Behold!

The jaws of darkness do devour it up;

So quick bright things come to confusion.

A Midsummer Nights Dream

Foreword

If a proud tower had fallen in Europe, a new and better one was anticipated in its place. The carnage of 191418 had been the war to end all wars, the war to make the world safe for democracy. Dynamic new successor states were rising from the debris of expired autocracies. Political revolution was wresting the social terrain from once privileged elites. Had a climate of authentic freedom and justice for the Continent dawned at last?

There was a sure and certain indicator. It was the Jews. No people ever had experienced more of the Old Worlds underside, its legal, vocational, and physical repression. If the worst of the prewar inequities and anachronisms were now to be stripped away, the Jews would be the first to know. Indeed, with their uniquely survivalist commitment to peace and freedom, it was inevitable that they should be the first to hurl themselves into the Continents explosive new chain reaction of political, economic, and cultural transformations.

Thus, in Eastern Europe, the Jews, long a people unto themselves, would press the cause of ethnic self-determination to its farthest linguistic and communal dimension. In both Eastern and Central Europe, for that matter, political messianists among them would lead the struggle for a classless, even utopian society. And in Central and Western Europe alike, Jewish liberal intellectuals would function at cutting-edge political and cultural engags.

Neither before nor since that postwar era has the fate of Europes Gentile majority and its Jewish minority been entangled as intimately, as passionately, as contentiouslyas ferociously. Was the symbiosis in the end a productive one? Was the dream of an ongoing entwinement of destinies a puerile illusion or a visionary, even heroic ideal? Students of history will draw their own conclusions, as this historian has drawn his.

In the preparation of this work, I have benefited from the generous observations and suggestions of colleagues and friends. They can only be listed here, with my warmest appreciation. For Poland and the Ukraine: Professor Antony Polonsky of Brandeis University, Professor Ezra Mendelsohn of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Professor Muriel Atkin of George Washington University. For Rumania: Professor Leon Volovici of the Hebrew University and Ms. Eva Gover of Tel Aviv, formerly Lecturer at the University of Bucharest. For Hungary: Mr. Charles Fenyvesi of Dickerson, Maryland, journalist and author.

For Czechoslovakia: Ms. Paula Zeigova of Prague, historian and teacher, and Professors Hugh Agnew and John Heins of George Washington University. For Austria: Dr. Stephen Beller of Washington, D.C., scholar and author. For Germany: Professor Henry Friedlander of the City University of New York, president of the German Studies Association, and Professors Mary Beth Stein, Andrew Zimmerman, Peter Rollberg, George Steiner, and Nathaniel Comfort of George Washington University. At the universitys Gelman Library, for access to publications in a wide variety of sites: Dr. David Ettinger, Research Director, International Relations and Social Sciences; Mr. Glenn Canner, Associate Director of Inter-Library Loans; and Ms. Kim Tohuyen, Director of Consortium Borrowing.

Ms. Jane Garrett and Mr. Melvin Rosenthal of Alfred A. Knopf, my editors and close friends, have collaborated as intimately in this project as in our numerous earlier joint ventures. Eliana Steimatzky Sachar, my wife and tireless proofreader, has remained an indispensable partner in these endeavors for thirty-eight years. My father, Dr. Abram L. Sachar, the pioneering author of Su ferance Is the Badge (also published by Knopf, in 1940), was the inspiration for a work on Europeans and Jews in the aftermath of the Great War. No longer with us, he remains that inspiration.

H.M.S.

Kensington, Maryland,

May 14, 2001

I

A MURDER TRIAL IN PARIS

A Prosecution Begins

At 10:00 a.m. on October 18, 1927, the gates swung open to the Assize Court of the Seine, the fourth of five courtrooms in the Palace of Justices stately complex. Some fifteen hundred persons, who had clogged the entryway since early morning, pressed forward to a chamber whose woodpaneled galleries accommodated barely four hundred spectators. Nearly half of them were journalists, many from other countries. They had come to witness a murder trial. Although both the victim, Simon Petliura, and the accused, Sholem Schwarzbard, were natives of the former tsarist empire, the crime had been committed in Paris a year and a half earlier.

Upon taking his seat on the dais, Presiding Judge Georges Flory informed the twelve jurors that French law permitted simultaneous criminal and civil actions. Accordingly, the victims widow, Olga Petliura, and his brother, Oskar Petliura, were sharing in the prosecution. Judge Flory then turned to the prisoner in the dock. Sholem Schwarzbard, thirty-nine, was a pale and diminutive man, yet with the muscular physique of a bantamweight boxer. He listened impassively while the judge defined the various charges of premeditated homicide, as listed in Articles 294298 and Article 301 of Frances Criminal Code. Flory explained that all carried the death penalty. How did the defendant plead? To each charge, Schwarzbard responded with an emphatic not guilty. Hereupon the judge invited Public Prosecutor Chrtien Reynaud to present the case for the state. The ensuing trial would continue for eight days.

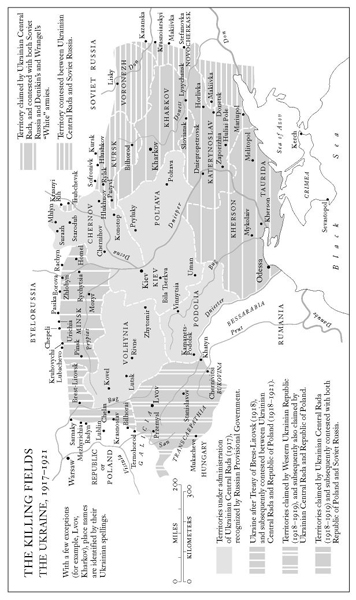

The basic facts of the defendants life by then had been extensively described in the world press. Schwarzbards hometown was Balta, a predominantly Jewish community in the former tsarist province of Podolia, where his parents owned a tiny grocery store. Baltas Jews intermittently were victimized by pogroms. In one of these, Schwarzbards pregnant mother was killed. The surviving four children endured lives of acute hardship. Sholem Schwarzbard as an adolescent was apprenticed to a watchmaker in a neighboring village. During Russias Octobrist Revolution of 1905, the seventeen-year-old youth was imprisoned for participating in an antigovernment demonstration. Upon his release three months later, he and his younger brother Meir fled Russia, working and often begging their way through Europe, before finally settling in Paris in 1910. There they opened a watchmakers shop.

Although the brothers soon married and assumed family responsibilities, their reaction to the outbreak of war in 1914 was characteristically uncompromising. Both immediately enlisted for military service, and both were assigned to the French Foreign Legion. Afterward, both suffered wounds in the Somme campaign, and both were awarded the Croix de Guerre. It was during his convalescence in a military hospital in February 1916 that Sholem Schwarzbard first learned of the immense tragedy that had befallen his people in Russia the year before. In December 1914, as the German army launched its offensive on the eastern front, Russias supreme military commander, Grand Duke Sergei, classified the dense Jewish population in the tsarist borderlands as a potentially subversive element. These people, he decreed, should forthwith be transferred away from the principal battle zones. Thus began, in March 1915, a systematic expulsion of Jews from Russian Poland, Lithuania, and Courland. Ultimately, some half-million men, women, and children were uprooted and driven into the Russian interior. Wherever transportation was provided, the exiles were packed into freight cars and dispatched to inland villages on a waybill. But scores of thousands of others were indiscriminately herded eastward without a fixed destination. Often they subsisted in wagons, boxcars, even in open fields. At least sixty thousand Jews died of starvation and exposure during the vast expulsion. Hundreds of thousands of others suffered economic ruin.

Next page