Richard C. Keller is professor in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics at the University of WisconsinMadison. He is the author of Colonial Madness: Psychiatry in French North Africa, also published by the University of Chicago Press, and editor of Unconscious Dominions: Psychoanalysis, Colonial Trauma, and Global Sovereignties.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13 : 978-0-226-25111-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13 : 978-0-226-25643-6 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226256436.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keller, Richard C. (Richard Charles), 1969 author.

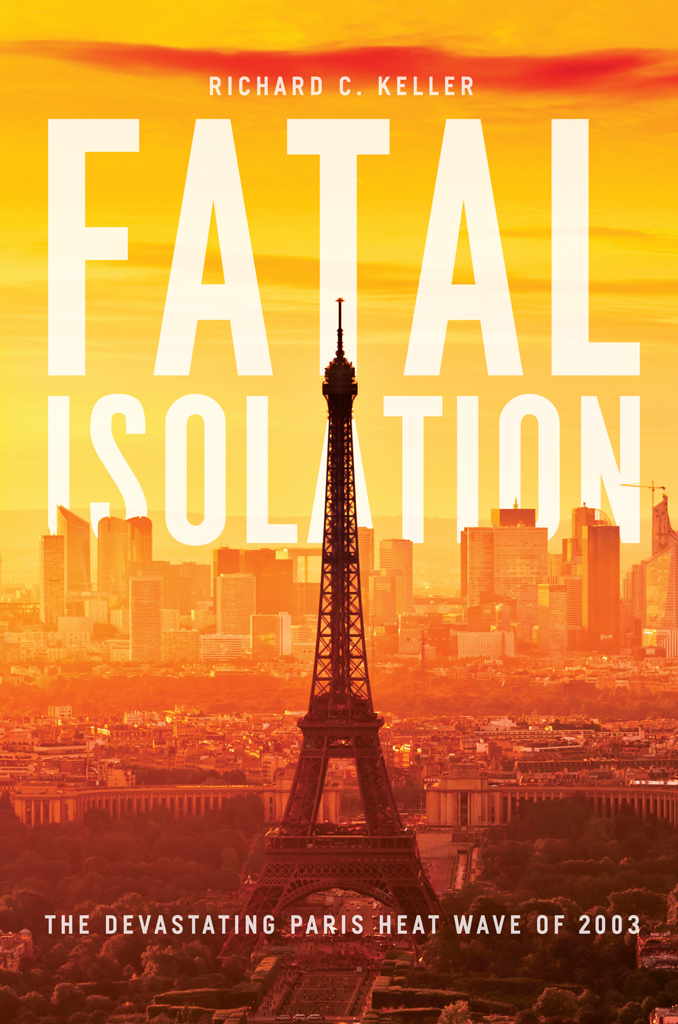

Fatal isolation : the devastating Paris heat wave of 2003 / Richard C. Keller.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-25111-0 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 0-226-25111-x (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-25643-6 (e-book) ISBN 0-226-25643-x (e-book) 1. Natural disastersFranceParisHistory21st century. 2. Heat waves (Meteorology)FranceParisHistory21st century. 3. Disaster victimsFranceParis. 4. Paris (France)History21st century. I. Title.

GB 5011.48. K 45 2015

363.3492dc23

2014036980

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Situated roughly a dozen kilometers southeast of central Paris, the suburb of Thiais lies about midway between Orly Airport and Rungis Market. It appears at first like many of the depressed communities of the banlieue, the peri-urban region of the Paris suburbs. The four-lane D60 national highway separates it from its neighboring suburb of Chevilly; several buses along this corridor link the southeastern suburbs with the Paris Mtros terminus at Villejuif. The highway itself is lined with big-box stores, filling stations, and fast-food chains, punctuated by stands of couscous and Greek sandwich restaurants. But as the highway nears Thiais it becomes clear that another industry predominates in the town of 28,000. Florists, funeral services, and monument producers abound, bordering a vast open space that sits behind a forbidding gate on the southern side of the highway, the Parisian public cemetery of Thiais.

Unlike the better-known Montparnasse and Pre-Lachaise cemeteries in Paristhe burial places of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Oscar Wilde, and Jim Morrison among dozens of other celebritiesa sizable portion of the cemetery of Thiais is dedicated to those buried at public expense. At the southern extreme of the cemetery lie four divisions that are colloquially known as the secteur dindigents or poor section. Each contains about 200 identical individual tombs, labeled with engraved brass tags bearing the victims name, along with birth and death dates. In each division, several rows of tombs remain unlabeled, indicating that their occupants are unidentified. These plots are owned by the city of Paris and serve as temporary repositories for the unclaimed bodies of those who die within the citys limits or in several suburbs. Many of these graves are filled with the bodies of the homeless, buried at public expense when no family member claims them. Others

FIGURE Division 58 in the Thiais cemetery. Photo by the author.

At the time of this writing, roughly a hundred bodies in divisions 57 and 58 at Thiais are those of victims of the heat wave of 2003, the worst natural disaster in contemporary French history (see A catastrophe linked to a high pressure front that remained static over western Europe for weeks in August of that year and assailed much of the Continent with record-high temperatures, it was a disaster that inflicted the greatest damage on the poorest and most isolated populations in France, as these bodies suggest. They are the so-called abandoned or forgotten victims of the disaster, whose bodies remained unclaimed by family. They are those who died (and to a great extent lived) unnoticed by their neighbors, only discovered in some cases weeks after their deaths. And they are those who rapidly became the symbols of the disaster for a nation wringing its hands over the mismanagement of the heat wave and the social and political dysfunctions it revealed.

The devastating heat wave or canicule that swept through western and central Europe in August 2003 was by every measure an extreme event. The disaster hit France particularly hard. Daytime highs reached 40C (104F) in Paris for days on end. More important, evening minimum temperatures dipped only to the low 20s C (low 70s F), giving bodies little respite from the heat even at night. Ozone pollution levels compounded the heats effects, and the duration of these temperatures for two weeks without relief made the climate insufferable. Catenary wires supplying electricity to high-speed trains melted, stalling travelers for hours in the heat with no power. The drought that France had experienced since February devastated trees to the extent that many Paris parksthe limited green space that might have protected some from the heats worst effectshad to be closed because of the danger of falling branches. The foundations of stone houses cracked because of the dehydration and settling of surrounding soil. The country suffered some four billion euros in agricultural losses. But far and away the greatest damage was the heat waves human toll: roughly 70,000 lives lost to the heat in Europe, and some 15,000 in France alone.

FIGURE Tombs in Division 58, Thiais. Photo by the author.

For the news media, for public officials, and for French citizens aghast at the heat waves merciless toll, however, one aspect of the disaster was particularly horrific. Weeks after the peak of mortality, hundreds of unclaimed bodies lay in Frances makeshift morgues, which included refrigerated trucks parked in the Paris banlieue and the food warehouses at Rungis Market.the origins and the management of the catastrophe. The publication of the names of the dead and their collective burial at Thiais were unprecedented events that reflected the exceptional nature of the crisis, but they were also important components of an emerging and consolidated narrative of the disaster. According to media and political rhetoric, these anonymous victims represented a failure of social solidarity in a culture of entitlement. They achieved public recognition only in death. And in most cases, these were deaths marked by profound indignity, suffered alone in dismal surroundings, while neighbors and public officials vacationed.

This book tells the stories of these victims and the catastrophe that took their lives. It explores three intersecting narratives of the disaster: the official story of the crisis as it unfolded and its aftermath, as presented by the media and the state; the anecdotal lives and deaths of its victims, and the ways in which they illuminate and challenge typical representations of the heat wave; and the scientific understandings of the catastrophe and its management. One of the books major contentions is that there are significant and even dangerous limitations to official representations of the disaster. A counterhistory of the disastera story of the heat wave from the bottom up, so to speakprovides an important means of contesting those narratives and signaling their incompleteness. The book therefore sets the informal, particular, and often-anecdotal knowledge generated in the collection of these victims histories of life and death in tension with the globalized, aggregative knowledge of the disaster contained in official reports, media treatments, and scientific analyses. By drawing on these stories it argues that the forgetting of those who died during the catastrophe was anything but accidental: that instead, a range of historical factors produced and conditioned the vulnerabilities that marked the victims lives and deaths. The development of the modern urban landscape in Paris, the perpetuation of social inequalities within its limits, and the political marginalization of the elderly and other vulnerable populations in the course of the last century have produced an unequal burden of risk, which the heat wave revealed with deadly force. From the ways in which the media and the state managed the heat disaster at its outset to the counting of its dead in its aftermath, these accounts of the heat wave point to the processes that pushed a population to the margins of citizenship and public visibility.