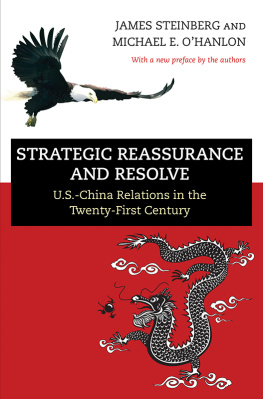

Copyright 2017

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

www.brookings.edu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

ISBN 9-780-8157-3110-8 (pbk : alk. paper)

ISBN 9-780-8157-3130-6 (ebook)

987654321

Typeset in Minion

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

CHAPTER 1

A Crossroads in U.S.-China Relations

W hat is the state of the U.S.-China security relationship with President Obamas term in office concluded and with Donald Trump in the White House? Given the centrality of this relationship to the future of the region and indeed the planet, as well as the emphasis that President Obama has appropriately placed upon it, the question bears asking at this milestone in history. The election of Donald Trump also requires reassessing first principlesboth because Trump was elected on a platform challenging many longstanding American foreign policy premises in general and because he articulated particular criticisms of U.S.-China relations.

Since Richard Nixons opening to Beijing in the early 1970s, there has been considerable continuity in U.S. policy toward the Peoples Republic of China (PRC). The pillars of this policy have included support for economic engagement and diplomatic partnership with China, combined with ongoing security commitments to regional allies, a U.S. military presence in Asia, robust trade and investment relations, and involvement with a range of multilateral institutions and partners. This strategy served U.S. interests well for decadeshelping pull the PRC away from the Soviet Union and thus accelerating the end of the Cold War while preserving security for Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and East Asia in general. The peaceful regional environment provided a context for Chinas leaders to launch a strategy of reform and opening up, which lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty and contributed to regional and global economic growth as transnational supply chains offered consumers lower prices for tradable goods.

As the decades went by, however, this strategy produced other consequences as well. China became the worlds top manufacturing nation, and boasted the worlds second largest economy, with dramatic consequences for jobs and investment, especially in the manufacturing sectors of developed countries, particularly the United States and Europe. These developments gave it the wherewithal to field the second most expensive military force, featuring a growing range of high-technology weapons that challenged Americas military supremacy in the Western Pacific. Workers complained of unfair trade practices while businesses, which had previously seen China as a market of enormous potential, increasingly saw China through the lens of protectionist regulations, intellectual property (IP) theft, and economic cyber espionage. Taken together, these developments led growing numbers of Americans to question whether Chinas rise was of mutual benefit either on the security front or on the economic front. The tension in U.S.-China relations was exacerbated because the hoped-for political reform, which was expected to follow the economic opening, failed to materialize. On the contrary, under President Xi Jinping, the movement toward a more open and rights-respecting China seems to have reversed course in favor of more central control and assertive nationalism that challenges what most in the United States consider to be universal principles of human rights. These internal changes were mirrored by a more assertive strategy on the international stage, ranging from Chinas increasing challenges to the status quo in the East China Sea and South China Sea to Chinas role in global and regional institutions.

The election of Donald Trump thus comes at a time when the value of the long-standing U.S. approach to China was already under stress and skepticism. During the campaign, Mr. Trump sharply criticized not only Chinas practices but the failure of the United States to respond effectively, as when he said the following on May 1, 2016, promising a new approach if elected: Were going to turn it around. And we have the cards, dont forget it. Were like the piggy bank thats being robbed. We have the cards. We have a lot of power with China. Following his election, the president-elect not only refused to temper his critique as some analysts expected, but actually raised the stakes to include the security realm by suggesting that the new administration might abandon the long-standing one China policy if China failed to address the president-elects economic concerns.

During his administration, President Obama sought to develop U.S. policy toward China to address some of these troubling trends, while preserving the basic framework of the one China policy. In Obamas first term, recognizing many of these dynamics, his administration articulated a policy of pivoting, or rebalancing U.S. relations with the Asia-Pacific region. The rebalance focused not only on security, but also on broader economic and political issues as well. This was generally well received among American strategists and leaders of both parties and among American allies

The troubles in the U.S.-China relationship do not automatically invalidate the logic of the rebalance. Many problems in the U.S.-China relationship predate the rebalance; indeed, as noted, they helped motivate Mr. Obama to articulate that new paradigm in the first place. Moreover, a strategy must be judged not only by its near-term achievement of objectives but also by the clarity with which it conveys core national interests and the conditions it establishes that may produce success over time. Nonetheless, it is safe to conclude that we have collectively reached a major milestone in the future of the U.S.-China relationship, and a period of fundamental reassessment.

If one dates the formal inauguration of the rebalance policy to Secretary of State Hillary Clintons Foreign Policy article on the subject in October 2011, followed by President Obamas visit to Australia and the broader region in November of 2011,territory throughout the South China Sea, turning seven land features into artificial islands capable of supporting aircraft and ships. President Xi promised, on a trip to Washington in late 2015, not to militarize the artificial islandsbut, in fact, the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) had already placed some military aircraft, ships, radars, and missiles on a number of them. Xis recourse was to blame the United States for militarizing the region first, justifying Chinas actions as a measured response. Throughout this period, China continued to be ambiguous about the meaning of its claim that the so called nine-dash line covered most of the South China Sea in a maritime zone of Chinese sovereignty.