The Senkaku Paradox

Risking Great Power War Over Limited Stakes

Michael E. OHanlon

Brookings Institution Press

Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2019

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

www.brookings.edu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: OHanlon, Michael E., author.

Title: The Senkaku paradox : risking great power war over small stakes / Michael E. OHanlon.

Other titles: Risking great power war over small stakes

Description: First edition. | Washington, D.C. : Brookings Institution Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001454 (print) | LCCN 2019009148 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815736905 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815736899 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesMilitary policy. | National securityUnited States. | Russia (Federation)Strategic aspects. | ChinaStrategic aspects. | Deterrence (Strategy) | Aggression (International law) | WarEconomic aspects. | Great powersHistory21st century. | Geopolitics.

Classification: LCC UA23 (ebook) | LCC UA23 .O347 2019 (print) | DDC 355/.033573dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019001454

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Adobe Caslon and Obvia

Composition by Elliott Beard

For my many awesome students over the years, from Georgetown and Johns Hopkins to Syracuse and Denver to Columbia and Princeton and beyond. And for Alice Rivlin, dear friend and Brookingss all-time greatest, as well.

Contents

Acknowledgments

I AM GRATEFUL to so many for help with the ideas in this book, as it includes elements of almost everything I have been learning and analyzing for decades, from high school in Canandaigua, New York, to college at Hamilton and Princeton, to graduate school at Princeton, to the Congressional Budget Office, to the Brookings Institutionand all the places Ive been privileged to teach along the way as well (including with the Peace Corps in the Democratic Republic of the Congo). For this project in particular, however, I would like to give special thanks to Duncan Brown and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, to Tom Ehrhard, Steve Rosen, and their colleagues at the Long-Term Strategy Group, to Jim Miller, Pat Cronin, Richard Fontaine, Bridge Colby, and other friends at the Center for a New American Security, to Mike Green and colleagues at the Center for Strategic and Institutional Studies, to Kurt Campbell at the Asia Group, to Harlan Ullman and his fellow advocates of porcupine strategies at Newport, to Ryan Williams and Jim Steinberg at Syracuse, to Ken Pollack and many more at the American Enterprise Institute, to Dave Mosher and other erstwhile colleagues at the Congressional Budget Office, to Phil Gordon and others at the Council on Foreign Relations, to Amy Chua and others at Yale, as well as to Dick Betts, Robert Jervis, Dipali Mukhopadhyay, and Steve Biddle at Columbia, to Keir Lieber and others at Georgetown, as well as Hal Feiveson, Ryan Crocker, and others at Princeton, to Richard Caldwell and Rachel Epstein at Denver, to several anonymous reviewers, and to a slew of brilliant Brookings scholars and friends who made specific contributionsincluding but not limited to John Allen, Celia Belin, Ben Bernanke, Richard Bush, Dan Byman, Tarun Chhabra, David Dollar, Robert Einhorn, William Finan, Cliff Gaddy, Bill Galston, Ted Gayer, Samantha Gross, Ryan Hass, Susan Hennessey, Steve Heydemann, Fiona Hill (in an earlier period), Jamie Horsley, Martin Indyk, Bruce Jones, Bob Kagan, Mara Karlin, Jamie Kirchick, Don Kohn, Cheng Li, Ian Livingston, Suzanne Maloney, Richard Nephew, Jung Pak, Ted Piccone, Steve Pifer, Alina Polyakova, Richard Reeves, Molly Reynolds, Bruce Riedel, Alice Rivlin, Frank Rose, Natan Sachs, Amanda Sloat, Mireya Solis, Constanze Stelzenmueller, Jonathan Stromseth, Strobe Talbott, Caitlin Talmadge, Shibley Telhami, John Thornton, Adam Twardowski, David Wessel, Tamara Wittes, and Tom Wright. Brookings and I are also grateful for the financial support of the Smith Richardson Foundation and the Sydney Stein Jr. Chair, as well as a number of other donors.

ONE

Introduction

Expanding the Competitive Space

ACROSS THE LAND AND AROUND THE WORLD, a debate rages over Russias return and Chinas rise.tional Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy .

But over what issues might war against Russia or China erupt? And if war were to occur, how might it be contained before it took the world to the brink of thermonuclear catastrophe? These are the concrete questions, set within the broader context of hegemonic change and great power competition, that this book attempts to answer.

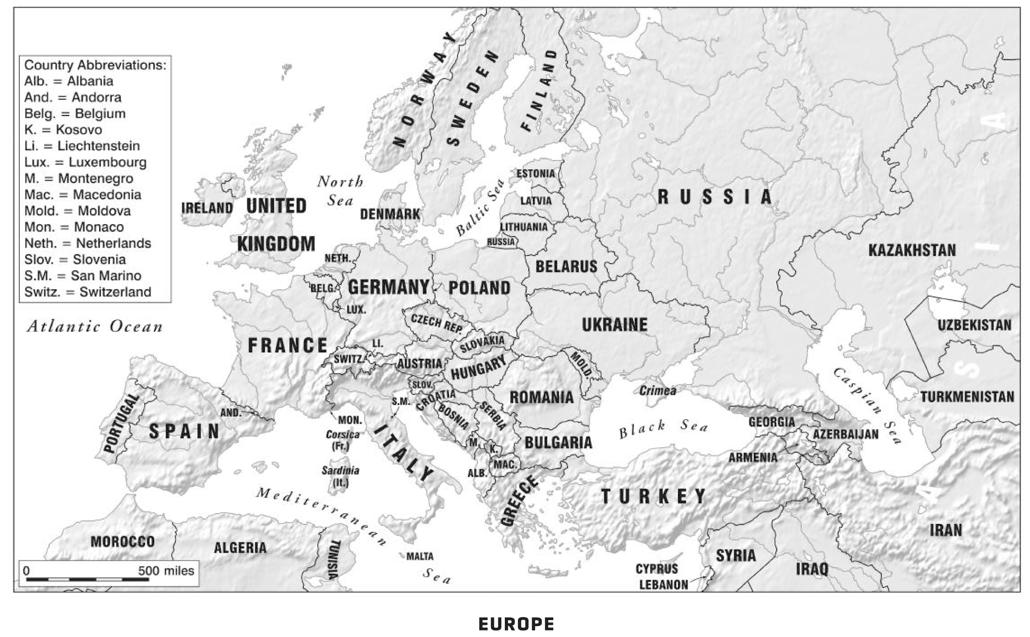

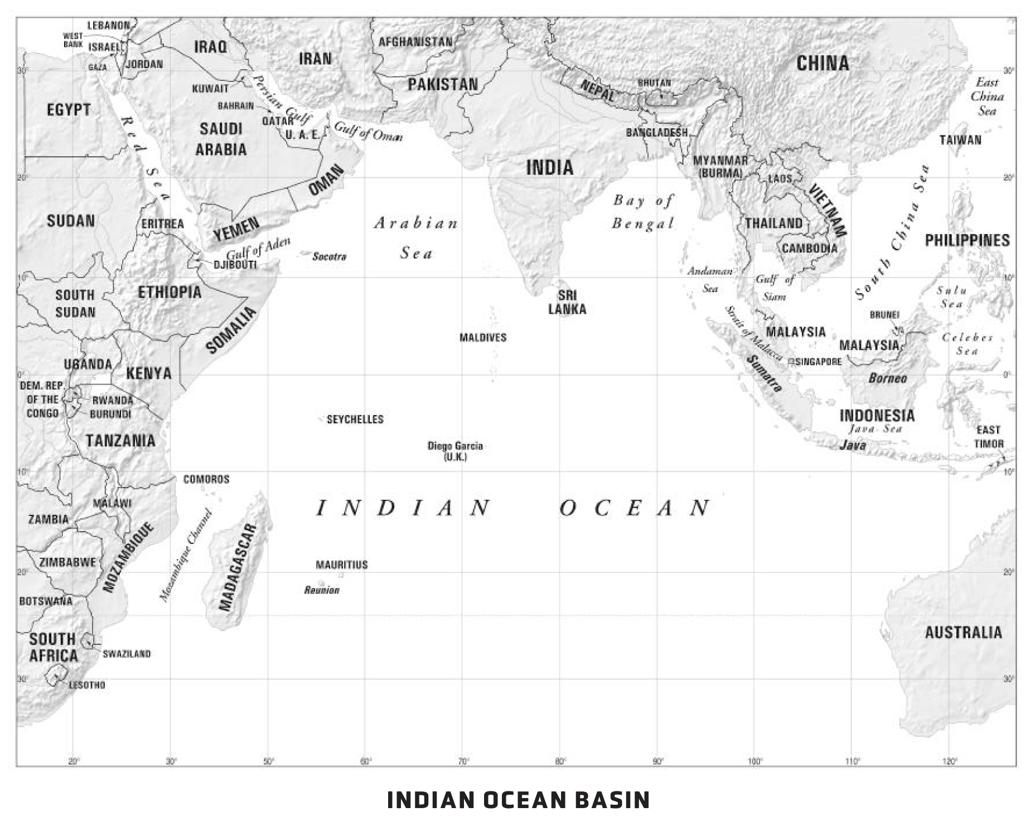

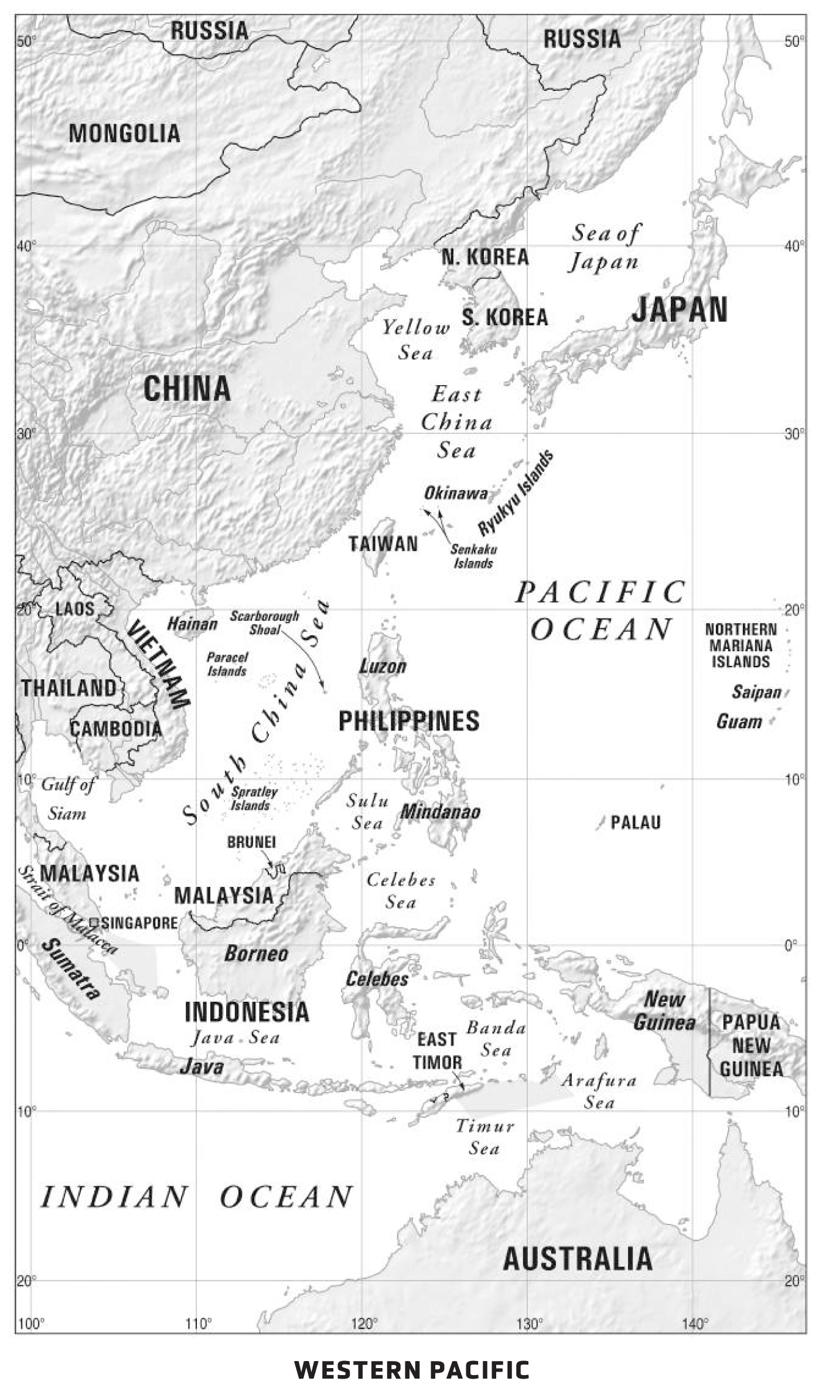

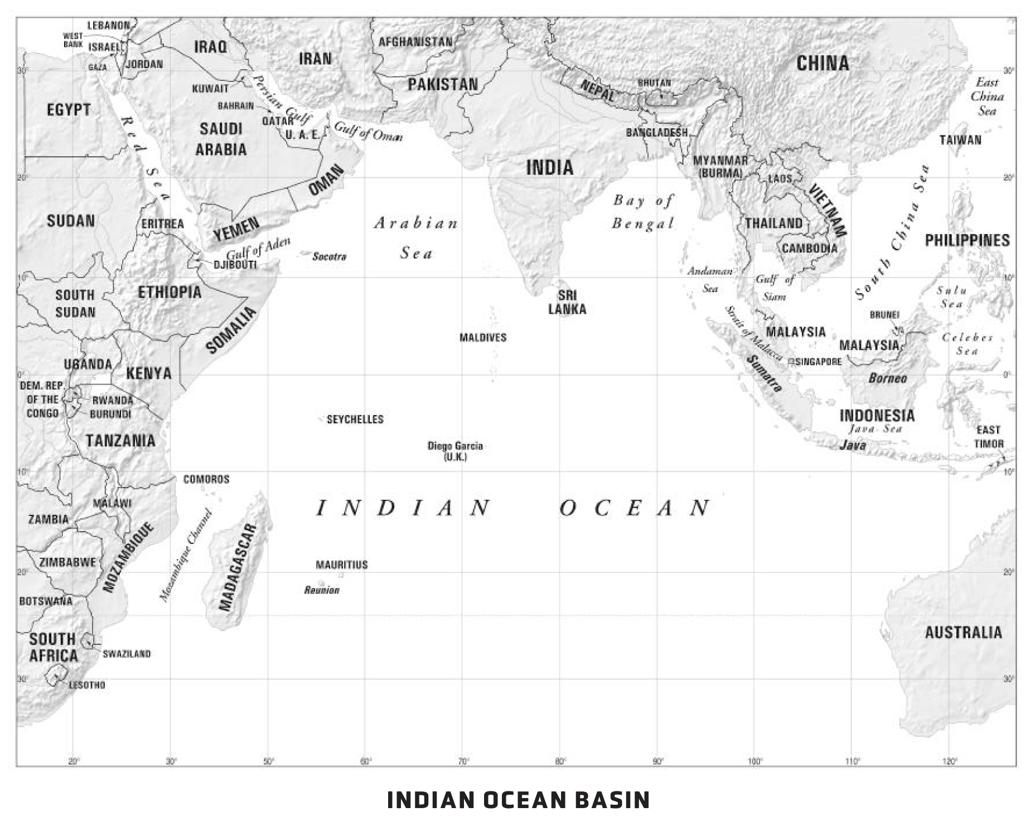

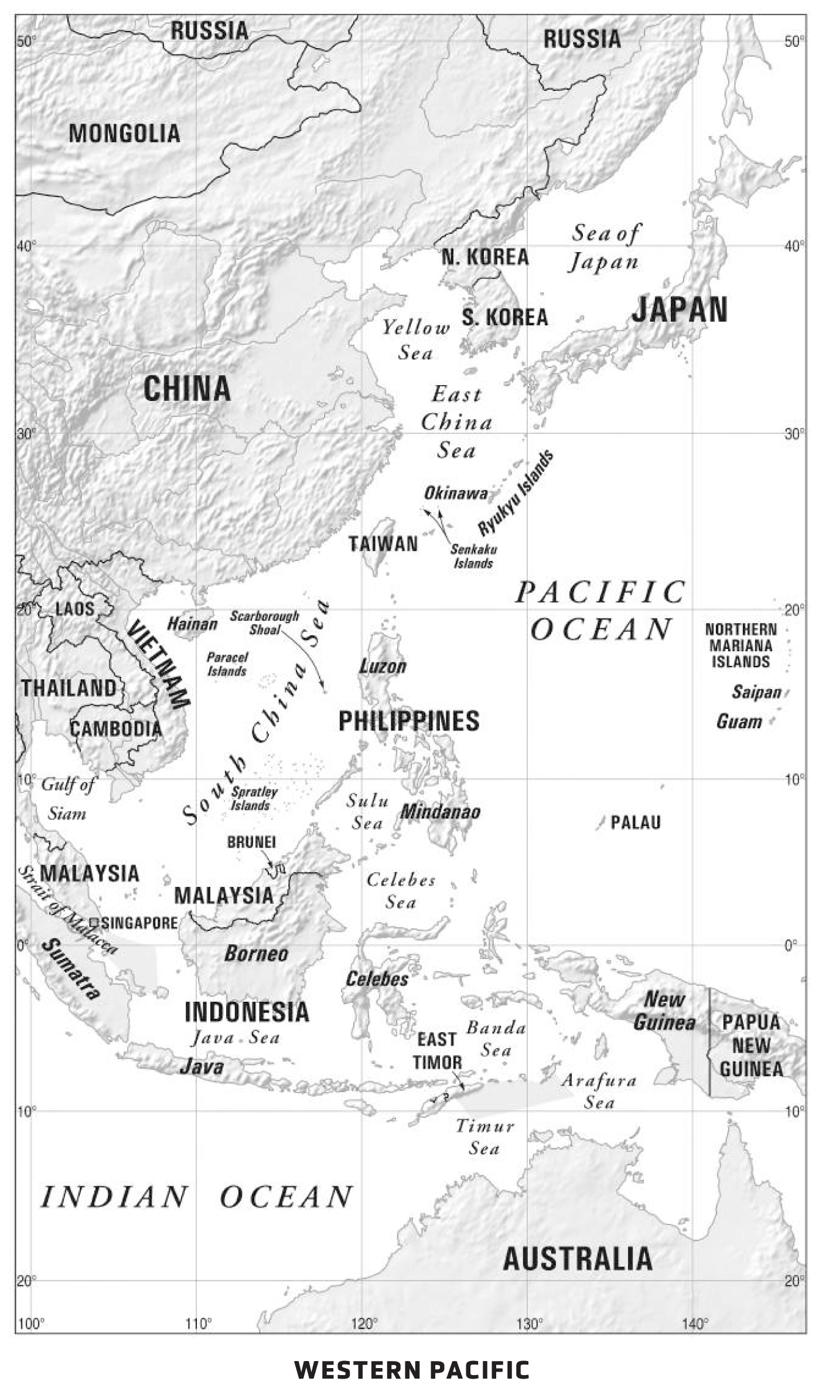

Specifically, I examine how a localized crisis started or stoked by Moscow or Beijing could expand and escalate. It is my contention that, especially in this period of history, such conflicts pose the greatest risk to great power stability and world peace. The signature case, which I have adopted for the title of the book, concerns the uninhabited and disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, claimed by both Japan and China. But the general problem has many possible manifestations.

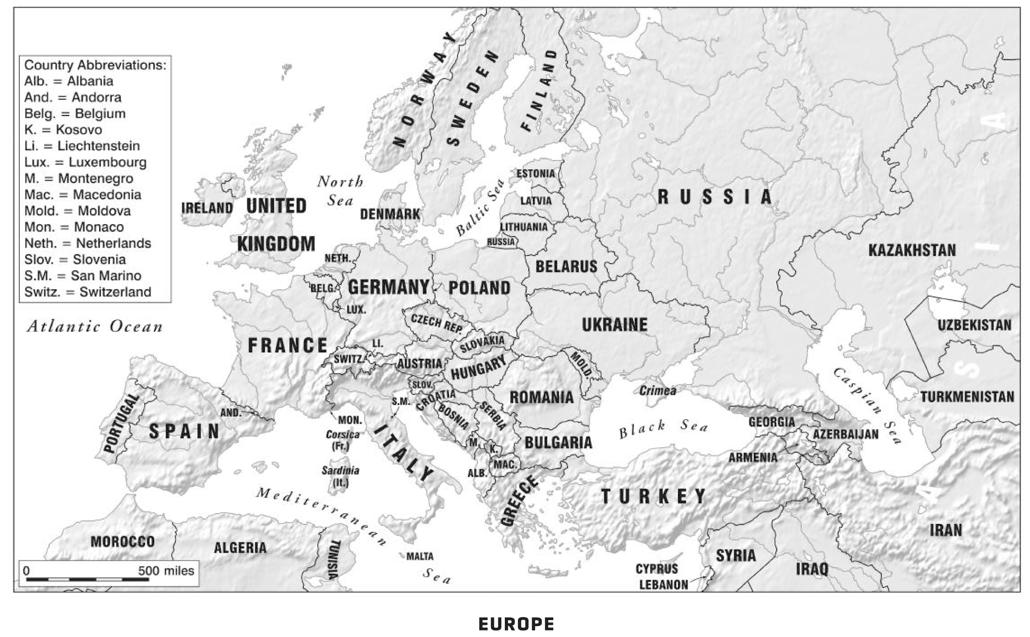

That one of these potential adversaries would launch a bolt-from-the blue, all-out attack against a U.S. ally seems much less likely than such limited aggression. It is hard to imagine a major Chinese invasion of the main islands of Japan or the metropolitan area of Seoul in South Korea, for example. And for all of Vladimir Putins recent adventurism, the forcible annexation of an entire NATO country, even a small Baltic state, strikes most as implausible. Such attacks, even if initially successful, would and should risk massive responses by the United States and its allies. President Donald Trumps tepid support for NATO, and for U.S. alliances in general, may muddy the deterrence waters somewhat. But even under his presidency, U.S. alliance commitments remain formally in place and American troops remain forward deployed from Korea and Japan to the Baltics and Poland. It would amount to a huge roll of the dice for an aggressor to seek to conquer any one of these states. To be sure, U.S. defense policy should continue to display resoluteness and create capacities of the type needed to deter such large-scale attacks, not just wishfully assume them away. But on balance, deterrence failure on such a massive scale seems very unlikely. Strong American-led alliances, conventional and nuclear deterrence, and economic interdependence all militate strongly against any conscious decision by an adversary to initiate large-scale war.