Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

2010 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute

material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights

and permissions department at (740) 5931154 or (740) 5934536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Baumann, Roland M.

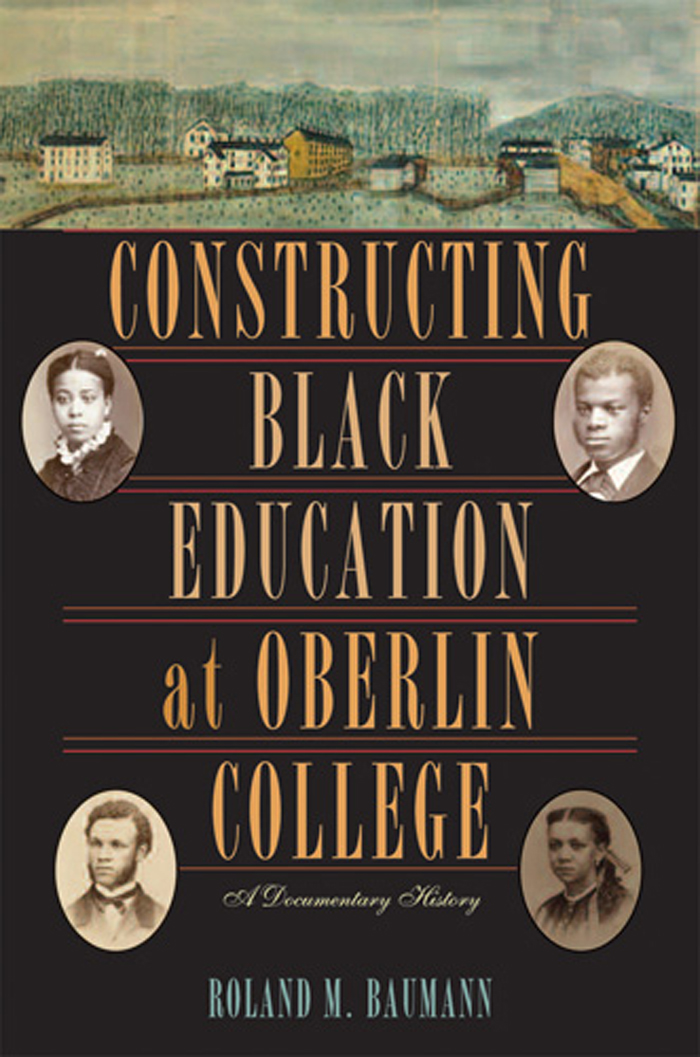

Constructing Black education at Oberlin College : a documentary history / Roland M. Baumann.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8214-1887-1 (hc : alk. paper)

1. Oberlin CollegeHistory. 2. African AmericansEducationOhioOberlinHistory19th century. 3. African AmericansEducationOhioOberlinHistory20th century. 4. College integrationOhioOberlin. I. Title.

LD4168.3.B38 2009

378.771'23dc22

2009028715

FOR MY WIFE, PHYLLIS,

OUR DAUGHTER, KARYN,

AND OUR SON, PHILIP

PREFACE

For more than a decade I have wanted to write about the educational opportunity and experience of black Americans at Oberlin College. In this endeavor, I follow the lead of Oberlins first archivist, William E. Biggle-stone, who built the road on which many of us have traveled. Most notably, he authored two important works, Oberlin College and the Negro Student, 18651940, Journal of Negro History 56 (July 1971): 198219, and They Stopped in Oberlin: Black Residents and Visitors of the Nineteenth Century, rev. ed. (2002). Occasional pieces, including Irrespective of Color and Straightening a Fold in the Record regarding the colleges first colored student, appearing in the Oberlin Alumni Magazine, round out his scholarship on the subject. Among the many local beneficiaries of Bigglestones scholarship are Geoffrey Blodgett, Gary Kornblith, Carol Lasser, Ellen N. Lawson, Marlene D. Merrill, and myself, as well as a number of nonresident scholars, such as William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, Juanita Fletcher, James Oliver Horton, and Cally L. Waite.

Like Bigglestone, I came to appreciate the potential value of the documentary sources on this topic held by Oberlin College in its archival groups and its manuscript collections. With the assistance of Leslie Farquhar 50, I published in the spring of 1990 a four-page brochure, Oberlin College: A Unique African-American Heritage. The target audience for this informational brochure was black alumni donors, who had contributed funds for the renaming of North Hall after John Mercer Langston, Oberlins most distinguished black graduate of the nineteenth century. More recently, I published a sixty-four-page booklet, The 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue: A Reappraisal (2003), which focused on the rescue of runaway slave John Price from the Kentucky slave catchers.

This volume is the product of my research to understand the black student experience at Oberlin College and the institutions commendable though uneven commitment to black education over the last 175 years. It draws heavily on the colleges unparalleled documentary recordthe number of preserved documents relating to this subject is significant. Personal accounts exist in the form of letters, reminiscences, and third-party documents by black and white students as well as other members of the academic community. These are supplemented by a wide array of institutional documents, both official and unofficial, which describe the changes in Oberlins cultural, religious, and academic perspectives over the years. Embedded in the documentary record is evidence of anger, fear, goodwill, miscommunication, misunderstanding, flash points on race, and political trivia. In addition, readers will find in the annotations and figure captions supporting information that adds details to the rich story of Oberlins experience. Together, these sources help explain the institutions path as it struggled to remain at the cutting edge of equity and access in higher education.

The documents in this book appear in chronological order. My objective in presenting them to readers is twofold: first, to provide a context for writers interested in the larger story of Oberlins place in the history of American higher education and in the history of African American education; and second, to foster an interest in reading and interpreting archival documents that relate to the African American educational experience at Oberlin and beyond. These documents contain many voices, and they offer important clues about how Oberlin faced the challenge of establishing a culturally diverse institution up to 2007. They also inform researchers about the actions and motives of individuals, both black and white, on many college campuses.

A note preceding each document introduces the reader to the text, its historical context, and sometimes its original meaning and provides an explanation of a given source. To ensure textual accuracy, each document is typically presented in its full form, with all misspellings, extra verbiage, inconsistencies, and stylistic characteristics intact. Editorial insertions are enclosed in square brackets. Words inserted in handwriting on the original documents appear in angle brackets. Crossed-out words are indicated as such. Contractions and abbreviations are retained as written. Dates, salutations, and closings are included as written but sometimes are set without line breaks to save space. When a word, phrase, or other portion of the text requires explanation, it is provided in an endnote. To further facilitate the work of future researchers and writers of African American history and Oberlin history, I have fully annotated the chapter introductions and the prefatory notes to documents. Finally, when quoting college administrators and faculty, I have tried to note their titles at the time.

In 2003, the African American Studies Department at Oberlin celebrated its thirtieth anniversary. In an address given at that event, Professor James C. Millette mused with reference to the institution of slavery during Oberlins founding year of 1833: Ive often wondered if, lurking somewhere in Roland Baumanns archives, [there] are documents which help to explain the origins of Oberlin College against this larger background of anti-slavery, and also help to explain its commitment to the welfare of Black people who were in the United States doomed to endure another thirty-two years of slavery before being freed. The two opening chapters of this volume offer a selection of nine documents covering the period 1835 to 1866. Twenty-one documents, divided among three additional chapters, provide a window into the less well known history of the Civil War and Reconstruction era to the present. These documents represent only a very small percentage of those that exist, for Oberlins documentary record is extensive in context, meaning, and sheer numerical possibilities.

Oberlins commitment to educate African Americans was not based on a single body of doctrine but instead was shaped by the cultural ideas coming out of the American Revolution and the Second Great Awakening; it was influenced as well by geography, faith, luck, and an openness to new religious viewpoints. Such a convergence of ideas and influences might well explain why the implementation of equal educational accesstested as it was by secular and other forcesresulted in the colleges inability to follow a straight line of progress. May others draw on this documentary history to build the larger story of black education achievement at Oberlin College and in America.