Storming the Heavens: African Americans and the Early Fight for the Right to Fly

Copyright 2018 Gerald Horne

Published 2018 by Black Classic Press

All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number:

Print book ISBN: 978-1-57478-151-9

e-Book ISBN: 978-1-57478-152-6

Printed by BCP Digital Printing (www.bcpdigital.com), an affiliate company of Black Classic Press, Inc.

To review or purchase Black Classic Press books, please visit: www.blackclassicbooks.com.

You my also obtain a list of titles by writing to:

Black Classic Press

c/o List

P.O. Box 13414

Baltimore, MD 21203

TABLE OF CONTENTS

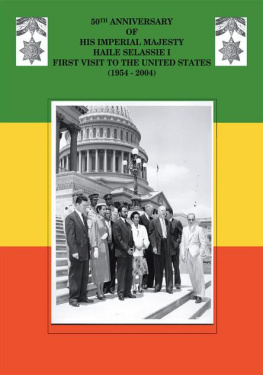

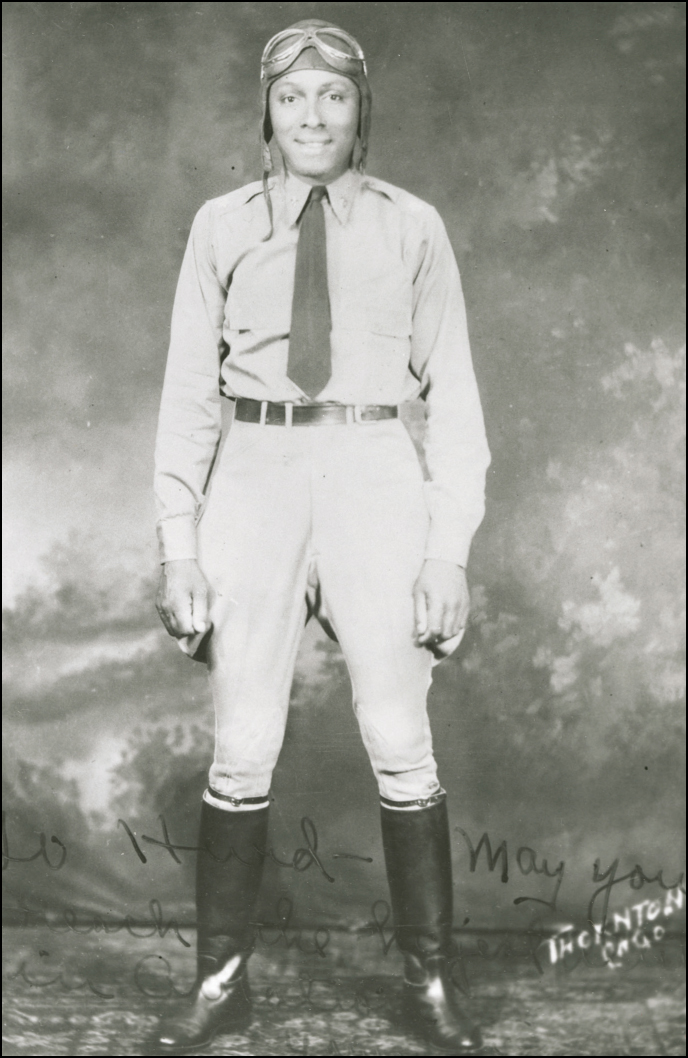

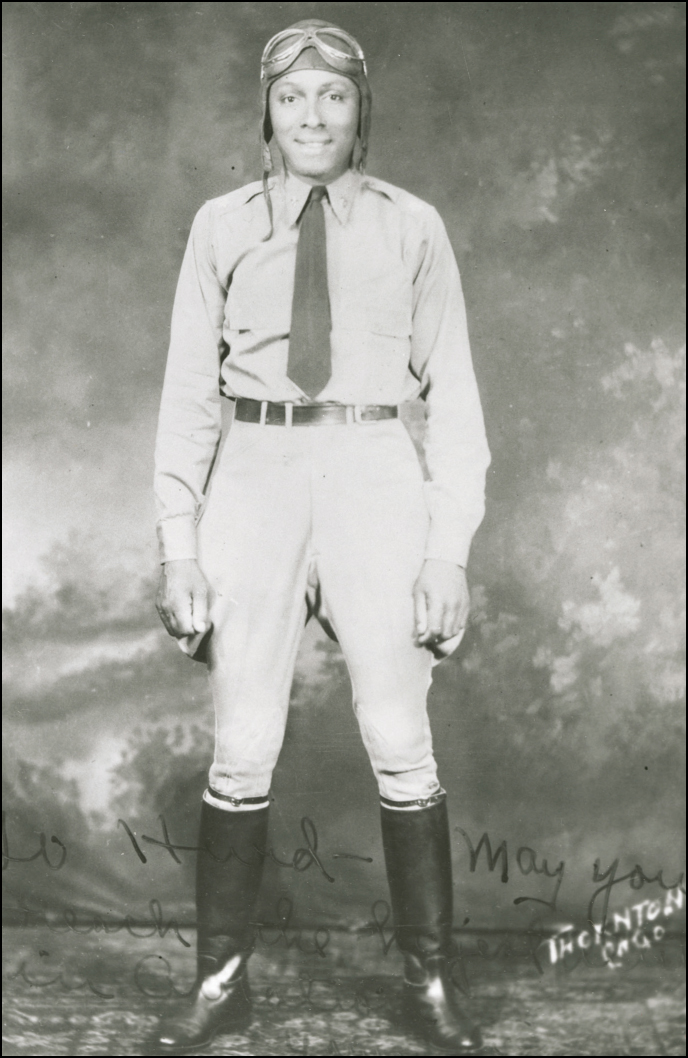

John Robinson. This Chicagoan volunteered to fight alongside Ethiopian forces in the 1930s after this nation was invaded by Italian legions; became a founder of Ethiopian Airways, the continents major carrier to this day.

(Courtesy Chicago History Museum).

INTRODUCTION

One minute, John Robinson was soaring through the skies of Ethiopia. The next, his hopes for surviving were plummeting precipitously.

It was late 1935, and this southern-born son of Black Chicago had chosen to take his immense piloting skills to Addis Ababa to assist the beleaguered regime of Emperor Haile Selassie I, His Imperial Majesty, the Conquering Lion of Judah, in foiling a brutal invasion by Benito Mussolinis Italian legions. Soon, Il Duces incursion came to be viewed as a harbinger of what was to be termed World War II.

Robinson had just departed from the city of Adowa in northern Ethiopia after it was bombarded twice. He was en route to Addis Ababa with some important papers when two Italian airplanes attacked him. As he noted later in a dispatch to the Associated Negro Press, the agency that had sponsored his volunteer journey: [The] Italians started shooting. I will never forget that day and the day after. I really had the closest call I have ever had, he added with relief, One part of the wing on the airplane I was flying had ten holes when I landed.

African Americans early interest in aviation reflected a longing for modernity and cosmopolitanism, especially since, as one analyst maintained, Afro-diasporic people, to their painful detriment, have been popularly constructed as backward and anti-technology.

These Black inventors were not alone in this quest. One writer credits the Wright Brothers relationship to the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar with helping to spark early Negro interest in aviation. and yet another tool to be deployed to subjugate African Americans and their colonized cousins in Africa and the Caribbean. The better part of wisdom dictated that Blacks learn more about flying. The airplane fed militarism and allied conservatism, which in turn buoyed a closely related colonial mentality and Negro-phobia.

As early as 1906, Sir Hiram Maximwhose invention of a fully automatic machine gun had won him pride of place among colonialistsacknowledged the potency of aviation as an instrument of warfare. He added ominously that it behooves all the civilized nations of the earth to lose no time in becoming acquainted with this new means of attack and defence.

* * *

In 1939, the then-reigning celebrity, Paul Robeson, beamed proudly that his son was already interested in aviation engineering and that he had bundled him off to Moscow for flight training. Robeson cautioned astutely that one could only imagine what a chance a Negro aviation engineer would have in the United States or in England.

The U.S. would be compelled to take halting steps away from Jim Crow, not least because of the national security implications exposed by Spears defection. Indeed, the departure of Robinson and others to far-flung global sites was a resonant symbol of the leakage of talent that represented a leakage of national security that conceivably could be quite harmful to Washington. Assuredly, the ease of traveling to Moscow from the Americas, instigated by aviation, was a signal factor in the erosion of Jim Crow. As aviation helped to break the boundaries of segregation and second-class citizenship, the U.S. was compelled to adjust accordingly.

A similar process was unfolding in colonized Africa. By the 1920s, as a direct result of aviation developments and African Americans concomitant mastery of this new technology, a riveting notion took hold in southern Africa: that a liberating air force of U.S. Negroes would descend on that benighted region and eviscerate colonialism as pilots dropped balls of burning charcoal upon the colonizers. The fear that the airplane could become a tool of liberation soon became a reality.

Like Jim Crow, colonialism and apartheid were designed to confine Black bodies, but confinement hardly defined the reality experienced by Alex La Guma, a leader of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party. Writing from London in 1973, La Guma informed his leadership in Tanzania that while in Moscow, having just departed Cairo, he received a message from Helsinki asking him to participate in a meeting in Hanoi. It was an invitation he quickly accepted, then jetted off to Vietnam to forge an important alliance.

Both demarches hastened the suffocating isolation and subsequent demise of the Pretoria regime.

* * *

Of course, just as fire tempers steel for construction on one hand while fomenting destruction on the other, aviation too could be harnessed in malignant fashion. The Nazi chief of the Air Staff in Berlin, General Karl Koller, argued passionately for the eminence of aviation for his diabolical government. In words deemed worthy of retention by U.S. General Hoyt Vandenberg, former Chief of Staff of the Air Force and former Director of Central Intelligence, Koller proclaimed:

Everything depends on air supremacy, everything else must take second place. The supremacy of the sea is only an appendage of air supremacy [since] the country that has air supremacy and vigorously strengthens its air power over all other forms of armament to maintain its supremacy, will rule the lands and the seas, will rule the world.

Koller further stated that all plans for the defense of a country, a continent or a sphere of interest or for offensive operations must be

Understandably, U.S. Negroes were hardly indifferent to this Nazis way of thinking. When the Black Wall Street of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was bombed from the air in a racist pogrom in 1921, many Blacks came to believe that their very survival depended on the study of aviation becoming a priority.

The U.S. Negro press was likewise alert when the then-avatar of aviation, Charles Lindbergh, was said to have declared in late 1939 that if the white race is ever seriously threatened, it then may be time for us to take our part in its protection, to fight side by side with Europe against its numerous colonized subjects. But not, Lindbergh added, with one against the other for our mutual destruction.

The prevalence of lynch laws in the United Statesyet another weapon in the arsenal of racism deployed against African Americansmeant that Lindberghs rancidness could not be ignored easily. Indeed, those sentiments heightened the need to counteract the advantage in the skies held by those who shared Lindberghs views.

Next page