University of Missouri Press

Columbia and London

Copyright 2011 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 15 14 13 12 11

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1919-0

This paper meets the requirements of the

American National Standard for Permanence of Paper

for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Design and composition: K. Lee Design & Graphics

Printing and binding: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

Typefaces: Palatino and Trebuchet

, Junior Commandos, is adapted from a chapter in Lisa M. DeTora, ed., Heroes of Film, Comics, and American Culture: Essays on Real and Fictional Defenders of Home, 2009 by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC 28640.

ISBN 978-0-8262-7249-2 (electronic)

To Roger and Susan Ossian, my parents, fans, and critics

Preface

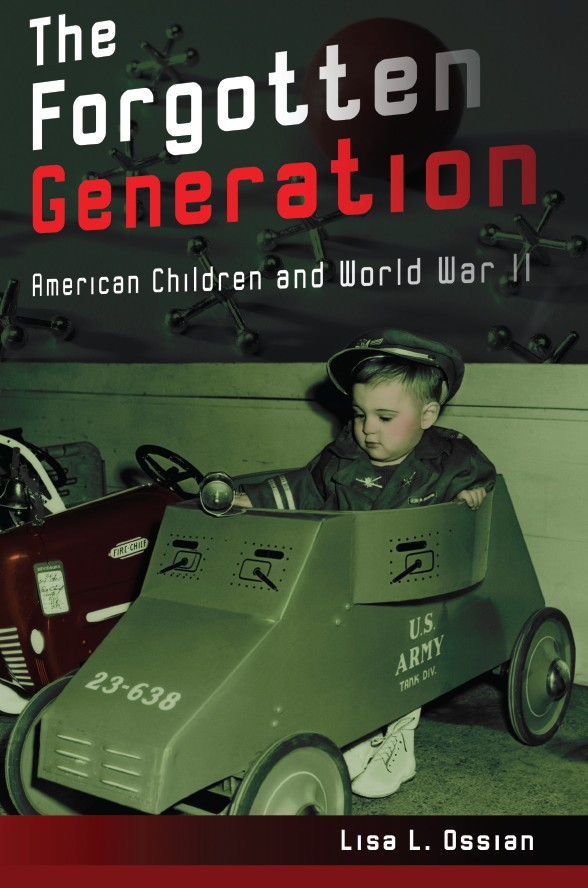

The Paradox of Children

It was a paradoxical alignment of principles and priorities, and the more Americans emphasized the importance of their own rights and goals, the less they regarded or respected the rights or even the lives of groups of people they considered to be others.

Kerry A. Trask, Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America (2006)

A child's world always has had odd dimensions, as narrow as the backyard or a corner of the kitchen, but as broad as the imagination.

Reed Karaim, A New Era in Play, USA Weekend (December 1416, 2007)

Children have always presented a paradox: time and energy, devotion and discipline, joy and grief, heartache and headache, money and still more money. And the writing of the history of children also presents its dilemmashow to portray and respect a generation not only through traditional historical sources such as newspapers, magazines, government documents, educational reports, and census data but with an ear for children's own voices and an eye for particular young vantage points to capture and paint a true portrait of children's historical lives.

Children often have a skewed sense of chronologycertainly the days march on, but the order is easily mixed up. Linear time gets slightly out of order, becoming circles and spirals. (Swings. Teeter-totters. Merry-go-rounds.) Children crave a rhythm of repetition, routine, and pattern, yet they also yearn for the height of holidays and crazy celebration, especially Christmastime. (Presents. Gifts. Rewards.) Children can have surprisingly single-minded and devoted focus to their tasks when motivated, yet free play must necessarily remain part of their lives for emotional and moral development. (Baseball. Tag. Hide and seek.) Playing not only encourages the imagination but provides an outlet to relieve stresses. (Kick the can. Cops and robbers. War games.) This wish for fun is a deep human need, not easily or wisely suppressed even in times of war. (Dolls. Bikes. Tea sets. Guns.) Children also respond particularly and easily to the verbal story along with the love of a pun or rhyme that delights and persists within the memory. (Sing-alongs. Radio shows. Comic books.) Children also crave attentionpositive or negative. All of this I have tried to include and reflect upon within this history of the Second World War.

Think back to your own childhood. Who were the most important people in your young personal narrative? When were you born? Where did you attend school and how would you describe the experience? Who loved, encouraged, cared for, neglected, frightened, hurt, or taught you? What images are flashpoints, forever memorable? What has been lost? What has been distorted or exaggerated? What still seems hazy or mysterious? Where did you live? Where do you still long to be? Which foods do you crave? Where and when were you afraid? What gave you pride? Whom did you respect? Whom did you hate and whom did you love? When did you leave home? How are you similar to other members of your generation? How have you changed? Why do we continue to refer back to our childhood in so many conscious and unconscious ways? Why?

With those questions in mind, I and other historians have searched for sources of information about children's actual lives during particular historical eras. Answers. Documents. Phrases. Images. Omissions. Myths. Truths. And still more questions. Startling discoveries and regular routines. Unique. Ordinary. Patterns. Whatever happened during our childhoods, good or bad, almost always stays with us deeply, consciously and unconsciously. Youth is by chance, yes, but childhood is important and forever.

As abstract as children's perceptions can be, children believe very deeply in concrete issuesdefinite ideas of right and wrong, black and white, us and them. The other. A wartime era only intensifies these characteristics. Feeling is far more important than knowing. Events and spaces can be much larger than reality. How did this complete paradox of experience affect American children's perception of World War II? How did they become the forgotten generation?

Acknowledgments

At the entrance leading to the fountains of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., the lead-colored panels lining the path demonstrate the varied stories of American citizens during this extensive world war. Six children appear among the numerous adults in these twenty-four memorial scenarios: a child listens to the Pearl Harbor news on the radio; a newsboy sells papers with the headline Germany Declares War; three children march in a parade, carrying flags and selling war bonds; and a boy celebrates V-J Day by proudly displaying his own American flag. Children always participated in a variety of daily activities and memorable events that composed the home front era, yet one must carefully observe the details of this almost forgotten generation's contributions to the Second World War. This was a people's war, states the last memorial's inscription by Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby, and everyone was in it.

As I stopped to read this last inscription by Colonel Hobby, my cell phone chirped with a text message from my teenage daughter: In 24 hours you will be in Iowa. Today's communication technology offers immediacy perhaps not available in the 1940s, but the messages conveyed still reflect those sent in children's letters and V-mails from World War II in that no child ever wishes to be forgotten. Children of both generations have reminded their parents to please come home.

Writing thank-you notes as a child always seemed necessary but difficult. I wondered why, if my heartfelt praise was within my spoken words and visible actions, I still needed to write it down on a card and send it off in the mail. But I didn't want to face Mom's wrath and I did want more presents in the future, so I would eventually sit myself down and write the best that I could do in a limited space. As an adult, writing the thank you's for a book presents me with the same dilemmahow, in just a few pages, to express my sincere praise with exactly the right words.

Only with family can one learn love and compromise, challenges and smiles. I certainly want to thank Mom and Dad (Susan and Roger Ossian, who were born during World War II) for always believing in me as a potential writer since I announced at the age of ten that I wanted to write big books some day, starting that day with my scrawled notes in a secretarial dictation tablet. My daughters Bailey, Nellie, and Brita have also taught me the deepest meaning of family while being relatively tolerant of my writing work. These three have always kept me grounded for over twenty years. They instantly insisted that their photo should also appear on this book's jacket because the knowledge I have gained as a mother has certainly enabled me to write a history of children.

This paper meets the requirements of the

This paper meets the requirements of the