STUDIES IN IMMIGRATION AND CULTURE

ISSN 1914-1459

ROYDEN LOEWEN, SERIES EDITOR

15 Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada: 19451989, by Jan Raska

14 Holocaust Survivors in Canada: Exclusion, Inclusion, Transformation, 19471955 , by Adara Goldberg

13 Transnational Radicals: Italian Anarchists in Canada and the U.S., 19151940 , by Travis Tomchuk

12 Invisible Immigrants: The English in Canada since 1945 , by Marilyn Barber and Murray Watson

11 The Showman and the Ukrainian Cause: Folk Dance, Film, and the Life of Vasile Avramenko , by Orest T. Martynowych

10 Young, Well-Educated, and Adaptable: Chilean Exiles in Ontario and Quebec, 19732010 , by Francis Peddie

9 The Search for a Socialist El Dorado: Finnish Immigration to Soviet Karelia from the United States and Canada in the 1930s , by Alexey Golubev and Irina Takala

8 Rewriting the Break Event: Mennonites and Migration in Canadian Literature , by Robert Zacharias

7 Ethnic Elites and Canadian Identity: Japanese, Ukrainians, and Scots, 19191971 , by Aya Fujiwara

6 Community and Frontier: A Ukrainian Settlement in the Canadian Parkland , by John C. Lehr

5 Storied Landscapes: Ethno-Religious Identity and the Canadian Prairies , by Frances Swyripa

4 Families, Lovers, and Their Letters: Italian Postwar Migration to Canada , by Sonia Cancian

3 Sounds of Ethnicity: Listening to German North America, 18501914 , by Barbara Lorenzkowski

2 Mennonite Women in Canada: A History , by Marlene Epp

1 Imagined Homes: Soviet German Immigrants in Two Cities , by Hans Werner

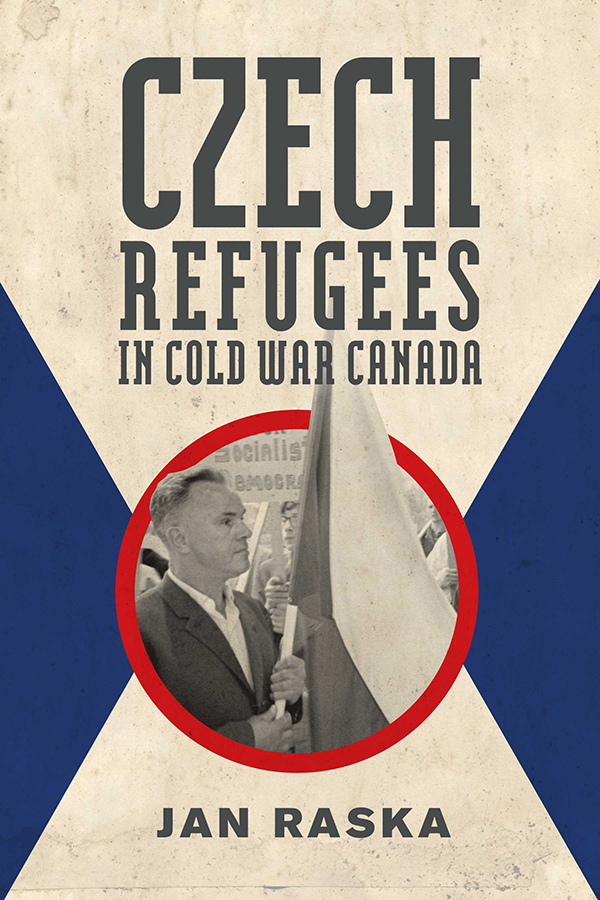

Czech

Refugees

in Cold War Canada

Jan Raska

Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada, 19451989

Jan Raska 2018

22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Studies in Immigration and Culture, ISSN 1914-1459; 15

ISBN 978-0-88755-827-6 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-88755-572-5 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-570-1 (epub)

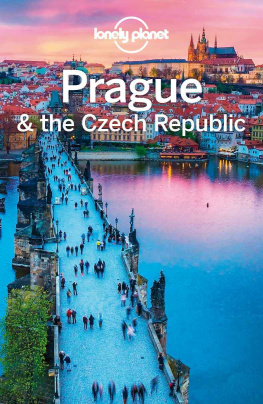

Cover design by Frank Reimer

Interior design by Karen Armstrong

Cover image: Czech demonstrators protest against the Soviet crackdown of the Prague Spring reform movement and communist aggression in Vietnam, Toronto, 22 August 1968. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC41068.

Printed in Canada

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Contents

Preface

Initially, my desire to learn about the shared past of Cold War refugees in Canada came from my own resettlement experience. In July 1985, just four years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, my family left Czechoslovakia in search of a better life and greater economic opportunities elsewhere. Like many Czech families, we applied for passports, in order to travel to communist Yugoslavia for a vacation. It was the only way for most individuals and families to leave Czechoslovakia. After we drove through Hungary and arrived in Yugoslavia, my parents sent a letter informing their siblings of our departure, and we left our possessions to them before the communist authorities became aware of our emigration and confiscated them.

In Yugoslavia, we spent the first two weeks near the Adriatic Sea in Croatia. We eventually left for Belgrade and stayed there for several days in a motel where other refugees from Eastern Europe were awaiting permanent resettlement in the West. In the Yugoslav capital, my parents applied for refugee status, under the United Nations Refugee Convention, with the local office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). During their interview with a UNHCR official, my parents were asked why it had taken them two weeks to request refugee status. They informed the official that they had wanted to visit the Adriatic Coast before heading to Belgrade. The visibly annoyed official, who had handled hundreds of similar cases, subsequently denied our claim for refugee status. My parents were later informed by other refugees at the motel that they should have stretched the truth or fabricated a believable story in order to acquire refugee status. Without options, my father reached out to his sister, who had immigrated to Canada in the late 1960s.

In November 1985, we left Yugoslavia for Canada. Our journey involved a transatlantic flight from Belgrade to Montreal. After landing in Canada, immigration officials asked my parents how we pronounced our family name, Raka (pronounced Rash-ka), since no h ek (a diacritical mark placed over certain letters in the Czech alphabet) existed above the letter s in the English language. The officials informed my parents that they could anglicize their surname to Rashka, or they could keep it the same, but the pronunciation would inevitably change. We eventually resettled in Ottawa and embraced our new Canadian home. Prior to receiving Canadian citizenship less than five years later, we officially chose to keep Raska as our family name.

Over the years, my parents have often told me stories about our journey to Canada. I soon began to consider the similarities and differences that our immigration experience had with other individuals and families from Eastern Europe, especially Czechs who came to Canada after the 1948 communist takeover of Czechoslovakia and the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion. Although their motivations for leaving Czechoslovakia and resettling in Canada were diverse, they were often viewed by successive generations as individuals who had left their homes because of political persecution and everyday life under a totalitarian regime.