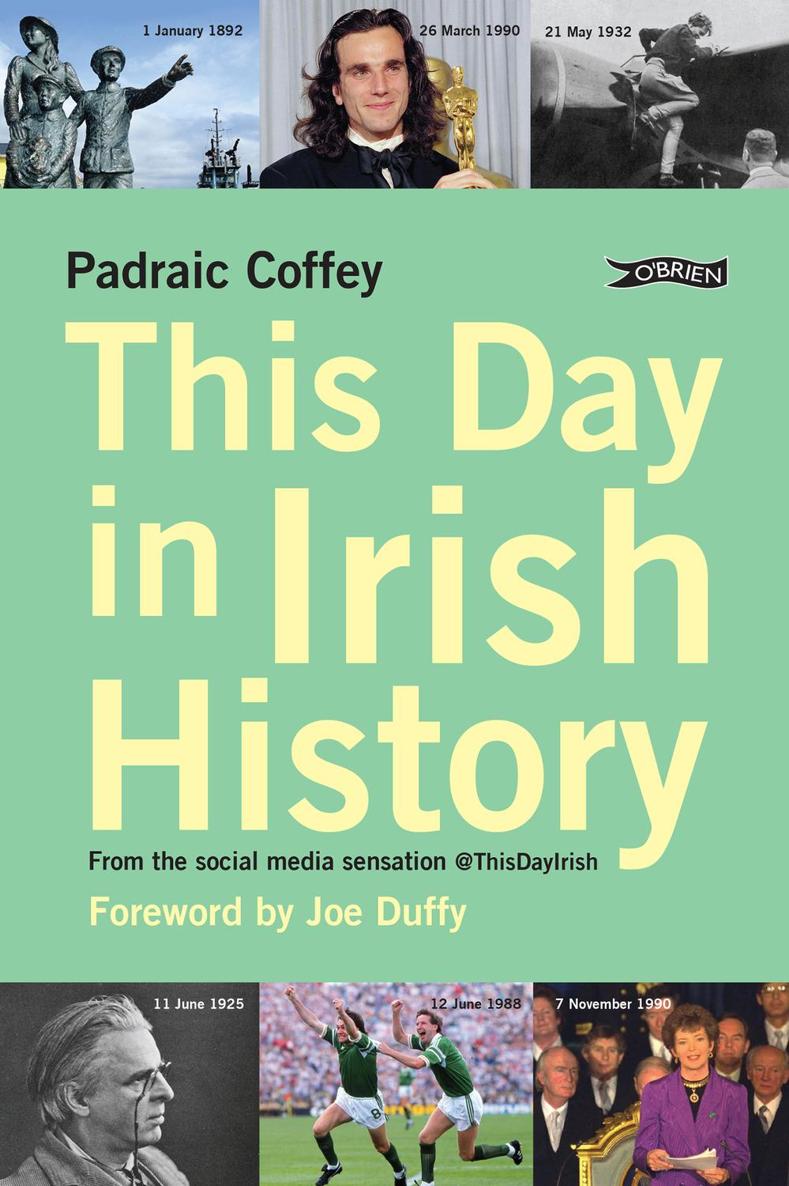

This is a monumental book. It is not only a collection of entries for the 366 days of the year (yes, Padraic with his attention to detail includes 29 February!) but also a fascinating social, political and economic history of Ireland and beyond.

Where else could you read in detail about John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Veronica Guerin, Sinad OConnor, Brigid McCole, Charlie Haughey, Ronald Reagan and Michelle Smith de Bruin in a single volume?

Places echo through these pages: the Statutes of Kilkenny, Glasnevin Cemetery, the Phoenix Park and Maamtrasna murders, Ellis Island and the Bachelors Walk killings are all to be found. I can think of no other book where Handels Messiah, James Joyces Ulysses, Shergar, U2, Riverdance and Seamus Heaney are written about in such engaging and accurate detail.

Battles of Glenn Mma, Clontarf, the Curragh, Dysert ODea, Knockdoe, Kinsale, the Boyne, Aughrim, New Ross, Ballinamuck, Ashbourne and the Bogside are retold in terms of their historical context and human cost. Given our tortured history, its no surprise that Bloody Sundays (London, Dublin and Derry), the IRA murder of Detective Garda Jerry McCabe, the Dublin, Monaghan and Omagh bombings, the Gibraltar killings and the false imprisonment of the Guildford Four feature among other horrific events etched into our memories.

It is a mark of the importance of each entry that when writing about the IRA murder of Lord Mountbatten, Padraic Coffey unlike some politicians and writers gives equal prominence to the three other people murdered in the attack: Doreen Bradbourne and two children, Nicholas Knatchbull and Paul Maxwell. He also notes that the man convicted of the murders, Thomas McMahon, was released early under the Good Friday Agreement and went on to work on Martin McGuinness failed presidential campaign.

We are reminded of avoidable tragedies, from Doolough to the Kingstown lifeboat disaster and fatal fires in Dromcollogher, St Josephs Orphanage in Cavan, Whiddy Island and the Stardust nightclub in Dublin. Often forgotten events that impacted our lives are of course included: an axe attack by suffragettes on the British Prime Minister on Dublins OConnell Bridge, the first Bloomsday, the Fethard boycott, the Bishop and the Nightie affair on Gay Byrnes Late Late Show, Josie Aireys successful campaign for free legal aid, women invading the Forty Foot. The smoking ban, the Ryan Report on child abuse in institutions run by the Catholic Church and the same-sex marriage referendum are brought vividly to life.

Names that mean so much to us simply by their mention St Colmcille, Roger Casement, Bernadette Devlin, the Maguire children, Mary Boyle, Philip Cairns, Ann Lovett, Bobby Sands and many more are given due respect and importance. The opening of the Guinness brewery, the first transatlantic telegraph cable, rural electrification, Myles na gCopaleens first newspaper column, the Arkle story, the 1979 papal visit, the Derrynaflan Chalice find and Irelands first Oscar winners feature in their glorious Technicolor and eccentricity.

Of course, the urge will be for you to go immediately to your birthday. Once you do, youll be hooked, because one of the joys of this book is that you can read it any way you choose: forwards, backwards or lucky dip! Whichever way you read it, you will find it unputdownable, educational, thoroughly enjoyable and historically accurate.

And I can fairly say it will appeal to all ages and interests: even to those who sometimes find books daunting! With an extensive bibliography and a chronology of events giving even more ballast, I guarantee that not only will you learn something new about our history and our lives, but you will be encouraged to read even more.

This Day in Irish History is a magisterial work of research, brilliantly written and beautifully presented.

Joe Duffy, broadcaster and author

1 January 1892: Annie Moore passes through Ellis Island

When Annie Moore stepped off the SS Nevada on 1 January 1892, little could she have known that she would be recorded as the first immigrant ever to pass through Ellis Island. Annie had departed from Cobh (known as Queenstown at the time), Co. Cork, with her brothers Anthony and Philip, aged 12 and 15 respectively. She was the eldest, at 17, and all three were travelling 3,000 miles to meet their parents, who had emigrated four years earlier and landed at the first US immigration station, Castle Garden.

Annie was the first of 12 million immigrants to pass through Ellis Island between 1892 and 1954, whose descendants comprise an estimated third of the people living in the United States. When she first saw the Statue of Liberty it had been in New York Harbour less than six years, having been dedicated on 28 October 1886.

The day after Annies arrival, the New York Times wrote: The honor [of being the first to pass through] was reserved for a little rosy-cheeked Irish girl. She was Annie Moore, fifteen [sic] years of age, lately a resident of County Cork. It would not be the last time that Annies age would be incorrectly recorded. When songwriter Brendan Graham penned his own tribute to Annie, Isle of Hope, Isle of Tears, he did the same.

In 2008, she was honoured at a ceremony in Calvary Cemetery, Queens, where a letter by then Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama was read out, which said: The idea of honoring those who came before you by sacrificing on behalf of those who follow is at the heart of the American experience. Irish Americans like your ancestors, and mine from Co. Offaly, understood this well.

2 January 1904: Arthur Griffith publishes The Resurrection of Hungary

On this day, the first in a series of articles by Arthur Griffith known as The Resurrection of Hungary was published in the United Irishman, the newspaper co-founded by Griffith in 1899. The articles would continue to appear until 2 July of that year. All 27 were collectively published under the same title, with the subtitle A Parallel for Ireland, in a pamphlet in November 1904.

Griffith had previously alluded to the Hungarian Policy in a speech at the third Cumann na nGaedheal convention on 26 October 1902, saying that members of the then dominant Irish Parliamentary Party should replace their policy of attending Westminster with the policy of the Hungarian deputies refusing to attend the British Parliament or to recognise its right to legislate for Ireland. Hungary, once dominated by its neighbour Austria, had reached the Compromise of 1867, which established a dual monarchy for the two countries and ended 18 years of animosity.