First published 2011 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2010052450

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Campbell, Penelope.

Africare: Black American philanthropy in Africa / Penelope

Campbell.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4128-4243-3

1. African AmericansCharitiesHistory. 2. Africare

(Organization)History. 3. PhilanthropistsUnted States.

4. African AmericansAfrica. I. Title.

HV590.C26 2011

361.77096091724dc22

2010052450

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-5254-8 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-4243-3 (hbk)

Contents

As with all authors, I am indebted to many individuals for information, insight, and encouragement. Additionally, there are those to whom I owe appreciation for their work in searching for documents and for assistance in the collection of materials.

There would have been no book without the cooperation of Africares four presidents. Each in his way was crucial to it. C. Payne Lucas first countenanced my idea to write a history of the organization and gave me valuable inside perspectives. His successor, Julius Coles, emphasized that I should write a study that presented Africare in a forthright and open manner. It was through him that William Kirker, the founder of Africare, was recognized for his role. Meeting Dr. Kirker, his wife Barbara, and several members of their Diffa team elevated my enthusiasm for the project. I regret that it has not been possible to include more about the work of the Kirkers in Niger. Finally, Darius Mans, following Julius Coles, was generous in sharing his goals as the new president.

Numerous other people, both within Africare and outside it, have been important contributors to my effort. Joseph C. Kennedy, director of international development, described the organizations methodology and aspirations. Staffmembers of field offices that I visited briefed me on their work and took me to see projects. Many persons allowed me to interview them. Some were Africare employees or former employees with experience working at headquarters in Washington or abroad. Others were retired USAID employees or men and women currently attached to charities, organizations, or businesses involved in humanitarian activities in Africa.

The mundane, but vital, task of locating research materials was handled capably by the Africare staffin Washington and by the librarians, under the direction of Elizabeth Bagley, at the Agnes Scott College Library in Decatur, Georgia. To both groups I am very grateful.

1

The Founding

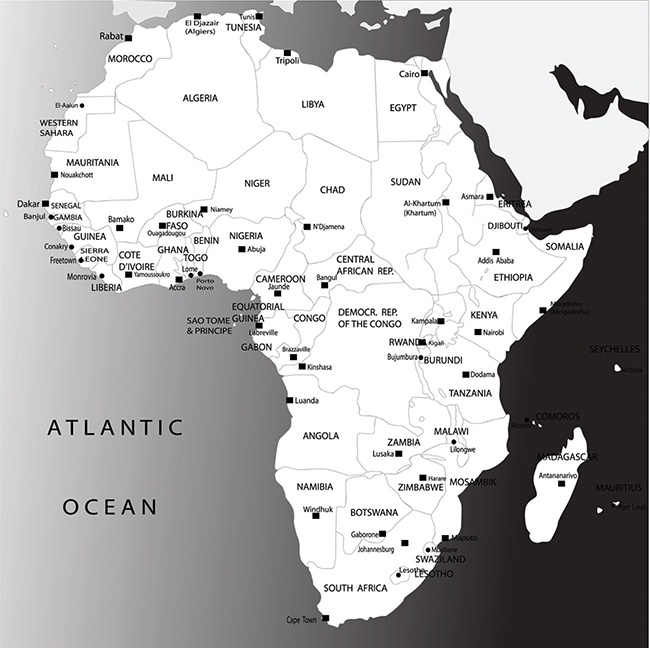

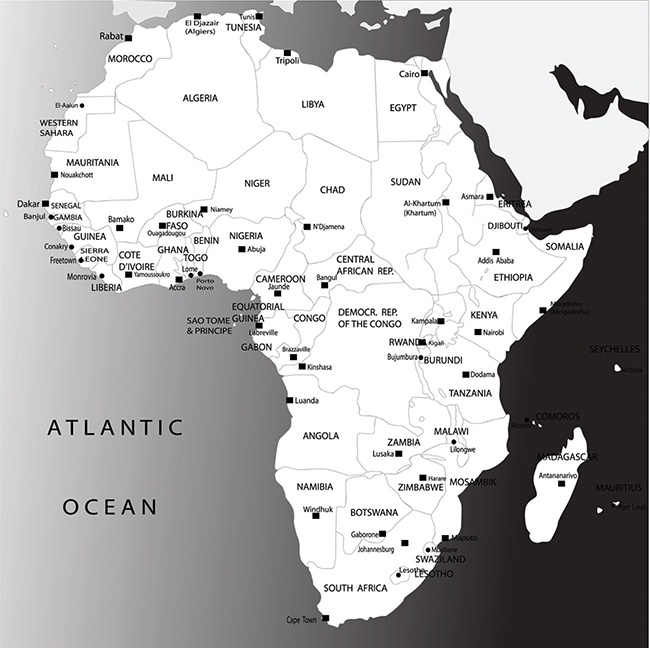

In the 1960s, Maine-Soroa was a village of fewer than a thousand inhabitants in the Department of Diffa, one of seven administrative units of Niger, West Africa. The area, in the far southeastern end of the country at the edge of the Sahara Desert, was a vast land the size of Michigan. Vegetation was mostly scrub, water was scarce, and resources sparse. Homes had no running water or electricity, and of the few telephones in the village, the most accessible was at the post office, which opened only a few hours daily. The roads were sandy and rutted and the sole other link to the outside world was an unreliable one-line telegraph. Kanouri, also known as Munga, was the dominant language spoken, and Hausa was an important second language. Maine-Soroa itself was divided into different living and functional districts. Most people lived in the villager area of grass huts surrounded by grass walls, although a few prosperous residents had adobe houses with corrugated tin roofs and mud walls. The business area, which included the mayors office, a grade school, and a police station, consisted of cement cinder block buildings with corrugated tin roofs. Town officials and businessmen usually lived in similar or adobe structures near this core. The hospital, with two buildings, one an outpatient center and the other an eight-room wing, was also cement block and had a corrugated tin roof. It did have a flush toilet with a ceramic basin, but that required the use of a hole in the ground and a bucket of water. There were no hotels in the village and the best accommodation available for visitors was in the school or in the mayors house. Cows, goats, and chickens roamed about. In a desolate place that had, at most, short, scant rains, the only other livelihood was an annual crop of millet, if the season was good.

Africare began in this African village, both figuratively and literally, and the African village has remained the focus of its work. The founders were passionate visionaries whose eyes were opened to the need in Africa by service in the Peace Corps and by the desire to perpetuate the Peace Corps humanitarian aspirations. They began modestly in Maine-Soroa, close to the confluence of four countries, never imagining that, in a few years, their effort would evolve into the only African American development organization in the United States planning life-sustaining projects in many nations of sub-Saharan Africa. However, Africare was not just an organization. It was intended to be a movement to bring Americans of all races together in a noble cause to save Africa. Millions became involved, and together with the men and women who devoted their entire careers to Africare, they hoped that their contribution toward African development would end poverty and disease on the continent.

Six hundred miles from Niamey, the capital of Niger, the villagers of Maine-Soroa began receiving help from American Peace Corps volunteers in the mid-1960s. One of these volunteers was William O. Kirker, a young Michigan physician who, having done his internship in Hawaii because his wife was Hawaiian, decided that the good life he could enjoy there in private practice did not match his understanding of the Hippocratic Oath. Asking himself if anyone in Hawaii would be worse off if he were not there giving medical care, and concluding no, he joined with thousands of idealistic Americans who believed that they could be of help to people abroad. Kirker and his wife, Barbara, were assigned to Niger and Kirker became one of three Peace Corps physicians working in the Department of Diffa. Patients came not just from Niger, but from other nations, Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon, in that crossroads near Lake Chad. Altogether, they spoke seven languages. Kirker, stationed in Maine-Soroa, found that meningitis was an annual epidemic, that malaria affected nearly everyone, and that tuberculosis was rampant. The average life expectancy was thirty-nine years and 50% of children died before they were five years old. He treated between one hundred to three hundred out-patients a day and performed sixty operations a month. Many of his most difficult cases were pregnant women with severe obstetrical complications. With limited actual medical experience and scant knowledge of African diseases, Kirker searched medical textbooks for advice on procedures and treatment. He also did a lot of praying.