About the book

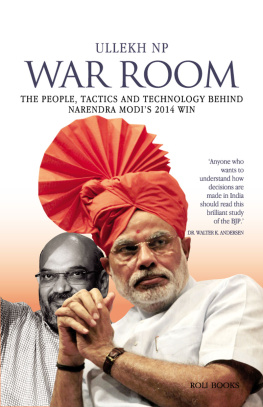

War Room stands out as an example of real field work and rigorous research Anyone who wants to understand how decisions are made in India should read this brilliant study of the BJP.

Dr. Walter K. Andersen, Author of The Brotherhood in Saffron: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Revivalism

Ullekh NP has crafted a well-researched and gripping narrative of how the BJP seized the moment in 2014. Its penetrating analysis of the personalities, politics and methods of Modi and Amit Shah makes it a useful resource for answering the major question of Indias near-term political future: Will the BJP in the Modi era realize its ambition of building 2014 to emerge as the dominant party nationwide?

Sumantra Bose, Professor of International and Comparative Politics, London School of Economics, Author of Transforming India: Challenges to the Worlds largest Democracy

Ullekh NP tells the story of Narendra Modis campaign to lead the worlds largest democracy. A man destined to reign on his own terms, Modi knew that being resilient was more important than being first and fast. Years after War Room is published, people will refer to it as the book that told the story of Indias most spectacular election in May 2014 in all its subtle and magnificent details.

Chitra Subramaniam, Award-winning Journalist and Author

ROLI BOOKS

This digital edition published in 2015

First published in 2015 by

The Lotus Collection

An Imprint of Roli Books Pvt. Ltd

M-75, Greater Kailash- II Market

New Delhi 110 048

Phone: ++91 (011) 40682000

Email: info@rolibooks.com

Website: www.rolibooks.com

Copyright Ullekh NP, 2015

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Roli Books. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

eISBN: 978-93-5194-068-5

Cover Design: Sneha Pamneja

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

FOREWORD

I n lucid prose, always precise never belaboured, Ullekh NP tells the story within the story of Modis ample victory. The story itself is what all attentive Indians lived through: the words, deeds, images and media-reported events that made up the election campaign. It is a rich and varied story but it is not what interests the author.

What he investigates is the inside machinery that produced the sounds and imagery of the campaign and even more, the inside politics that aligned national and local politicians with Modis trajectory to power, securing their fullest support if possible, their partial support if necessary, or at least their grudging respect and desistence.

When it comes to his investigative flair and persistence, readers might be most amused as well as instructed by his layer-by-layer uncovering of the true author of the hugely popular slogan Ab ki baar Modi sarkaar, which was claimed by all manner of worthies and even a tycoon, before it was prosaically revealed that it was the adman who created the ad, that is Piyush Pandey, executive chairman and creative director at Ogilvy & Mather, who in turn attributed his success in selling Modi to Modi himself: a fantastic product.

At a much deeper level, but always in light, fast, very readable prose, Ullekh probes the fundamental reason for Modis sweeping victory. He starts with the plain fact that his predecessor, Manmohan Singh, was not a fully empowered prime minister. That India with her immense diversities and multi-layered decentralization needs a PM who can really lead and powerfully, is obvious enough. But what it had under Singh was much less: Without doubt, the institution had lost its lustre under Singh as he waited for instructions from Sonia Gandhi. The role of the prime minister has been crucial for reforms. This was evident in the case of Narasimha Rao in 1991-1996 and AB Vajpayee in 1998-2004. But by 2011-12, the National Advisory Council (NAC), headed by Sonia Gandhi, had become an alternative power centre that was more powerful than the PMO. The casualty, of course, was governance.

That in turn lead to the wilting of the economy: Under Singh, expenditure and economic activity started shrinking. Employment generation, too, was slow. So was growth in manufacturing, which fell in several quarters in the last years of [his government].

Ullekh explains how the lack of leadership directly damaged investment, the very engine of growth:

The low-profile Manmohan Singh would never put his foot down when powerful Cabinet colleagues thrust indiscreet policies upon the government. The move to tax overseas companies for transactions that they had entered into in India in the past also shattered investor confidence in the Indian economy. One of the companies was the biggest foreign corporate investor in India, Vodafone. The tax department sent Vodafone a tax bill of Rs 3,200 crore for allegedly undervaluing the shares Vodafone issued to its parent company. The tax department said that this difference in valuation was in fact a disguised loan subject to transfer pricing provisions. Vodafone argued that share premium is a capital receipt, not income and hence not taxable. The case stretched on so long, it scared off potential overseas investors.

Weak leadership also crippled the engine of economic growth in other ways: [there was a] reluctance in giving clearances to such projects by the environment ministry under Jairam Ramesh first and then under Congress leader Jayanthi Natarajan, who faced unconfirmed charges of soliciting bribes for clearing projects. She had to finally step down from the ministerial post in early 2014 for, it appeared, delaying of projects for months without giving any plausible reason. By the time the seniors in the party took note and intervened, such criminal negligence of aborting new projects had done major damage to the Indian economy, already wobbling under the weight of deteriorating investor sentiment.

Ullekh finally uncovers the deepest layer of the preference for starving the goose that lays the golden eggs ideology:

Even when Singhs government (or rather Sonias) returned to power in 2009 without the Left, it continued to put a lot of emphasis on social spending Here was an opportunity to put the country back on the reform track. But [instead there was a] consistent expansion of its key entitlement-focused schemes.

![Ullekh N P - Kannur: Inside India’s Bloodiest Revenge Politics [Hardcover] ULLEKH NP](/uploads/posts/book/140966/thumbs/ullekh-n-p-kannur-inside-india-s-bloodiest.jpg)