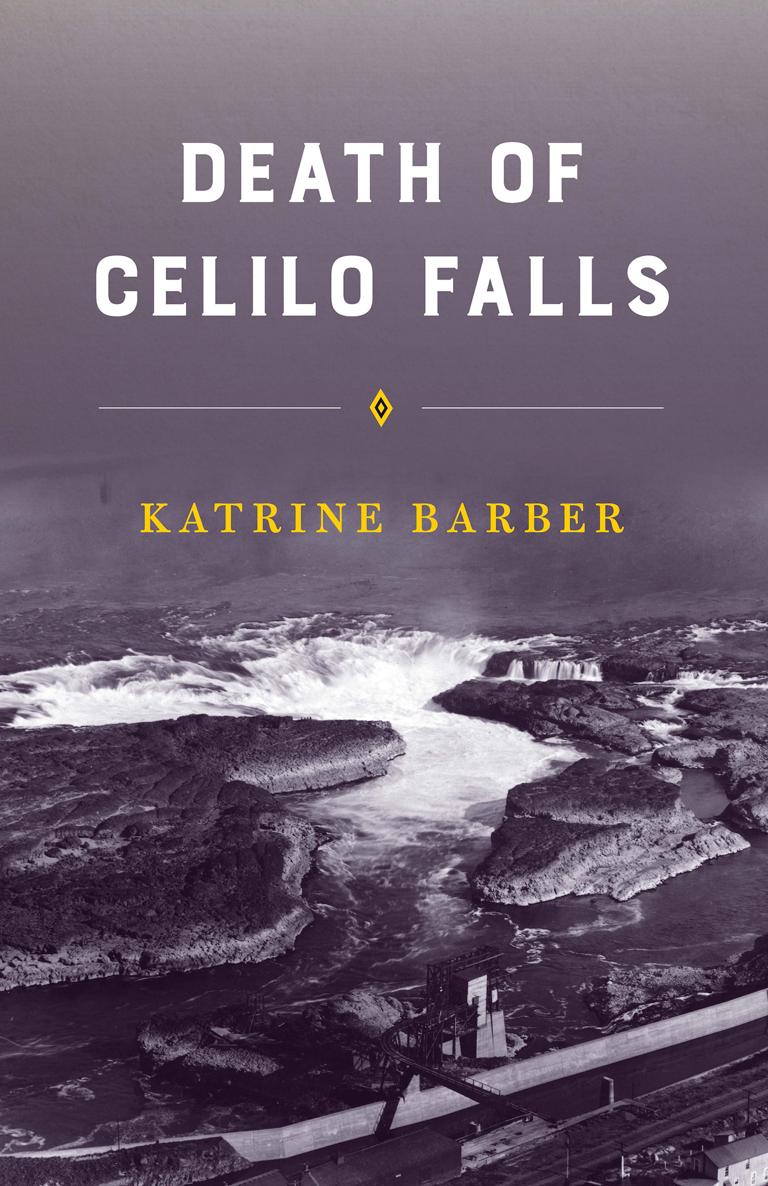

THE EMIL AND KATHLEEN SICK LECTURE-BOOK SERIES IN WESTERN HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY

Under the provisions of a Fund established by the children of Mr. and Mrs. Emil Sick, whose deep interest in the history and culture of the American West was inspired by their own experience in the region, distinguished scholars are brought to the University of Washington to deliver public lectures based on original research in the fields of Western history and biography. The terms of the gift also provide for the publication by the University of Washington Press of the books resulting from the research upon which the lectures are based.

The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 18051910 by Donald W. Meinig

Mills and Markets: A History of the Pacific Coast Lumber Industry to 1900 by Thomas R. Cox

Radical Heritage: Labor, Socialism, and Reform in Washington and British Columbia, 18851917 by Carlos A. Schwantes

The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 18641906 by Michael P. Malone

The Forging of a Black Community: Seattles Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era by Quintard Taylor

Warren G. Magnuson and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century America by Shelby Scates

The Atomic West edited by Bruce Hevly and John M. Findlay

Power and Place in the North American West edited by Richard White and John M. Findlay

Henry M. Jackson: A Life in Politics by Robert G. Kaufman

Parallel Destinies: Canadian-American Relations West of the Rockies edited by John M. Findlay and Ken S. Coates

Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century edited by Louis Fiset and Gail M. Nomura

Bringing Indians to the Book by Albert Furtwangler

Death of Celilo Falls by Katrine Barber

DEATH OF

CELILO FALLS

KATRINE BARBER

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST

in association with

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

2005 by the University of Washington Press

Designed by Pamela Canell

Printed in the United States of America

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 055 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest

P.O. Box 353587, Seattle, WA 98195

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data may be found on the last page of the book.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent postconsumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements

of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

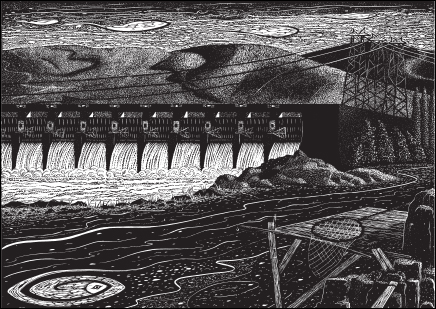

Title page image: Powers That Be, linoleum block print by Jonnel Covault

FOR MY TEACHERS, LIBERATORS ALL

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At Bonneville now there are ships in the locks The waters have risen and cleared all the rocks Shiploads of plenty will steam past the docks So roll on, Columbia, roll on

WOODY GUTHRIE, ROLL ON, COLUMBIA, ROLL ON (1941)

When they get us all pushed off the river, maybe they can build more places for the tourists and windsurfers. Maybe they can put up a nice little museum here with statues and pictures, so the gawkers can see what Indians once were like.

WILLIS, AN ELDERLY INDIAN FISHER IN CRAIG LESLEYS RIVER SONG, COMMENTING ON THE REMOVAL OF INDIAN PEOPLE FROM THE COLUMBIA RIVER AS A RESULT OF DAM-BUILDING

I grew up in Portland, Oregon, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, where I learned in grade school to sing Woody Guthries anthem to a rapidly changing Columbia. He wrote Roll On, Columbia, Roll On in 1941, along with twenty-five other songs, when he was briefly employed by the Bonneville Power Administration to sell the region on public power. A classroom visit from novelist Craig Lesley complicated my view of the river and its dams when I was a student at Jefferson High School. Lesley had just completed Winterkill, a novel that addresses the inundation of Celilo Falls (he would later publish River Song, which also deals with dam-building). This experience introduced me to the importance of Indian treaty rights and the many ways in which they have been challenged and prompted me to begin what became a decades-long research and writing project.

I was fortunate to have high school teachers who believed their students could understand the nuances of Indian treaty rights and who wanted us to understand the historical complexities of our shared home. Bill Bigelow and Linda Christensen raised my initial interest in this topic, provided me with crucial historic questions, and introduced me to a real author. Friends and teachers have continued to guide this work with considered criticism and timely encouragement. I must especially thank Professor William Robbins, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of History at Oregon State University. He provided me with convincing evidence that a working class kid could become an academic historian. Bill Robbins, Sue Armitage, Paul Hirt, Bill Lang, Peter Boag, Donna Sinclair, and Andrew Fisher read and commented on the entire manuscript, some of them repeatedly. I took much of their advice; of course, all errors are mine.

I was also assisted by Bob Kingston, Clark Hansen, Donna Sinclair, and Lucy Kopp, among others, at the Oregon Historical Society; Joyce Justice and John Ferrell at the National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Alaska Region in Seattle, Washington; Chuck Jones at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Portland Area Office; and Julie Kruger, the City Clerk at The Dalles. Barbara Mackenzie generously shared her time and stories of her experiences in The Dalles with me. Her son, Thomas Mackenzie, prompted her memory and shared family documents. My colleague Jan Dilg and I wrote a separate article about Barbara Mackenzie that dealt with, in part, her work relocating Celilo Indians. Our collaboration on that project made this book richer.

My colleagues at the History Department at Portland State University have supported this work financially and with their good guidance. Gordon Dodds, whom I replaced at PSU but whose shoes I will never fill, was a generous colleague whose advice and good humor I miss very much. I am especially fortunate to be a faculty member of the Center for Columbia River History, a partnership between Portland State University, Washington State University Vancouver, and the Washington State Historical Society. The center and my colleagues there have supported my research in Columbia River history, especially Bill Lang (founder and director of CCRH until 2003), Laurie Mercier, Mary Wheeler, David Johnson, Garry Schalliol, Candice Goucher, current director Sue Armitage, and Donna Sinclair.

Donna Sinclair has been a reader and sounding board, and shares my love of this place and its history. Our conversations have been especially influential in my understanding of this region. I am part of a circle of Pacific Northwest women historians and writers that includes Donna, Jan Dilg, Eliza Jones, and Jo Ogden. Each has contributed to this work and has ensured that historical research and writing is not always done in isolation. Margaret Sherve, who at this point should be included in family, is another colleague to whom I am much indebted. My families have also supported me financially and in spirit. I am proud to come from them.