This Republic

Illuminating Republican government

Will Butts

Libertys Lamp Books

QUINCY, MA

Copyright 2014 by Will Butts.

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed Attention: Permissions Coordinator, at the address below.

Cover Design by LLPix Designs

www.LLPix.com

Cover painting: John Adams by John Singleton Copley, 1783

Libertys Lamp Books

377 Willard Street #338

Quincy, MA 02169

www.libertyslampbooks.com

Book Layout 2013 BookDesignTemplates.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-9911175-1-2

This Republic. Illuminating Republican Government / by Will Butts

Contents

Chapter One:

The Framework of Republican Government

Chapter Two:

The Best Form of Government

Chapter Three:

The Consent of the Governed

Chapter Four:

The One, the Few, and the Many

in the Legislature

Chapter Five:

Separating the Legislative, Executive

and Judicial Powers

Chapter Six:

Preserving the Public Liberty

Appendix I:

Appendix II:

Appendix III:

For the American People

The preservation of liberty depends upon the intellectual and moral character of the people. As long as knowledge and virtue are diffused generally among the body of a nation, it is impossible they should be enslaved.

John Adams

chapter 1

What is a Republic?

The Framework of Republican

Government

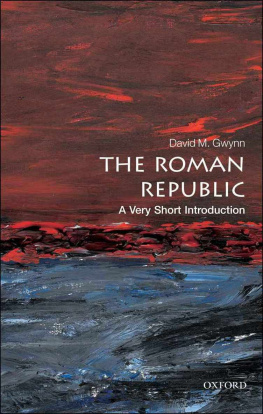

When the American republic was founded, it was just the latest in a long line of republican governments extending back to ancient times. From the Hebrew Commonwealth of the Bible; to Athens, Carthage, and Rome; to Venice, Geneva, the Netherlands; and even to the Kingdom of England, republican governments have spanned the centuries. But what exactly is this system of government? What was it the American founders endeavored to create? What is a republic?

To John Adams, a republic was an empire of laws and not of men.1 To James Madison, a republic was a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their office during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior.2 And to Roger Sherman, a republic was:

A government under the authority of the people, consisting of legislative, executive, and judiciary powers; the legislative powers vested in an assembly, consisting of one or more branches, who, together with the executive, are appointed by the people, and dependent on them for continuance, by periodical elections, agreeably to an established constitution; and that what especially denominates it a republic is its dependence on the public or people at large, without any hereditary powers.3

The law, the authority of the people, representative government, the balance of powers, and a written constitution: these are principles that characterize a government to be a republic. Yet these principles all stem from a single idea, the republican idea, the idea of the republic, the res publica:

The word res signified in the Roman language, wealth, riches, property; the word publicus, quasi populicus, and per syncope poplicus, signified public, common, belonging to the people; res publica, therefore, was publica res, the wealth, riches, or property of the people.

Res populi , and the original meaning of the word republic could be no other than a government in which the property of the people predominated and governed; and it had more relation to property than liberty. It signified a government in which the property of the public, or people, and of every one of them, was secured and protected by law. This idea, indeed, implies liberty because property cannot be secure unless the man be at liberty to acquire, use, or part with it, at his discretion, and unless he have his personal liberty of life and limb, motion and rest, for that purpose.

It implies, moreover, that the property and the liberty of all men, not merely of a majority, should be safe. For the people, or public, comprehends more than a majority, it comprehends all and every individual; and the property of every citizen is part of the public property, as each citizen is part of the public, people or community. The property, therefore, of every man has a share in government, and is more powerful than any citizen, or party of citizens. It is governed only by the law.4

Though republics existed long before Rome, the Latin term for the republican idea remained. Res publica translates literally as the public riches, the common wealth, or the property of the people. It translates more loosely as the public matter or the public thing. It is all of the people, all of their property, and all that concerns them, under the law.

For the idea of the res publica, or republic, is that the law is supreme; that every person and every thing would be governed, not by men, but by law, by a set of rules that applied to all:

Others more rationally define a republic to signify only a government in which all men, rich and poor, magistrates and subjects, officers and people, masters and servants, the first citizen and the last, are equally subject to the laws. This, indeed, appears to be the true and only true definition of a republic.5

The republic is the peoples affair. But the people is not just any collection of human beings gathered together in any sort of way, but the gathering of a large number of people associated by their agreement on the laws for the common good.6

The common good, the common wealth, the public riches, the public matter, the public thing, the peoples property, and the peoples affair: these are all variations of the res publica.

For the res publica is the law: the public thing created for the purpose of securing and protecting all individuals and all property. The law is for the entire public; therefore, it must apply to all, and none must be exempt from it. A government where law applies only to some and not to others would not be republican:

It may be laid down as a first principle, that neither liberty nor justice can be secured to the individuals of a nation, nor its prosperity promoted, but by a fixed constitution of government, and stated laws, known and obeyed by all.7

The laws, which are the only possible rule, measure, and security of justice, can be sure of protection, for any course of time, in no other form of government: and the very name of a republic implies, that the property of the people should be represented in the legislature, and decide the rule of justice.8

A republic is, therefore, a government of laws and not of men, because in a republic, all men are subservient to the law, to the res publica, to the common good.

But a republic is something further, for laws do not appear from thin air. Laws must be made; they must be written and enacted. And to make law is to legislate, from the Latin legis, meaning law or agreement, and latio, meaning to propose or bring forth. An individual lawmaker is thus a