No Way to Pick a President

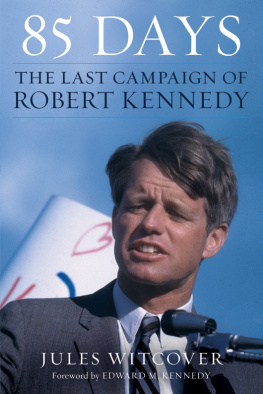

Also by Jules Witcover

85 Days: The Last Campaign

The Resurrection of Richard Nixon

White Knight: The Rise of Spiro Agnew

A Heartbeat Away: The Investigation and Resignation of Vice President

Spiro T. Agnew (with Richard M. Cohen)

Marathon: The Pursuit of the Presidency, 19721976

The Main Chance (a novel)

Blue Smoke and Mirrors: How Reagan Won and Why Carter Lost the Election of 1980 (with Jack W. Germond)

Wake Us When Its Over: Presidential Politics of 1984 (with Germond)

Sabotage at Black Tom: Imperial Germanys Secret War in America, 19141917

Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? The Trivial Pursuit of the Presidency, 1988 (with Germond)

Crapshoot: Rolling the Dice on the Vice Presidency

Mad As Hell: Revolt at the Ballot Box, 1992 (with Germond)

The Year the Dream Died: Revisiting 1968 in America

Published in 2001 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

First published in hardcover in 1999 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

First Routledge paperback edition, 2001.

Copyright 1999,2001, by Jules Witcover.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be printed or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Witcover, Jules.

No way to pick a president: how money and hired guns have debased American

elections / Jules Witcover.

p. cm.

Originally published : New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-93031-6

1. PresidentsUnted StatesElectionHistory. 2. Political campaignsUnited

StatesHistory. 3. United StatesPolitics and government20th century. I. Title.

JK5424.W58 2001

324.973092dc21

20010191266

For Peter, Corin, and Macey

Acknowledgments

A book drawn from more than forty years of reporting and writing on presidential campaigns and elections owes a profound debt to hundreds of colleagues, politicians, political professionals, voters, and friends made and maintained along the way. In the manuscripts early stages, sage advice came from my old friend the late John Chancellor. Many interviews helped me form and flesh out my ideas, particularly those with presidential candidates Lamar Alexander, Bill Bradley, Bob Dole, and Phil Gramm; vice presidential candidate Jack Kemp; former Republican National Chairmen Haley Barbour and Frank Fahrenkopf; former Democratic National Chairmen Don Fowler and Paul Kirk; and Charlie Black, Hal Bruno, James Carville, Kent Cooper, John Deardourff, David Doak, Sam Donaldson, Charles Lewis, Dick Morris, Mike Murphy, Joe Napolitan, the late Matt Reese, John Sears, Bob Shrum, Terry Smith, Stuart Spencer, Bob Squier, Lesley Stahl, Ray Strother, Bob Teeter, and Fred Wertheimer. My thanks to each of them.

In the solitude of the books writing, the list narrows and the debt deepens to a few who provided unwavering support and encouragement. These include my incomparable editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Elisabeth Sifton, and my indomitable agent, David Black. Most of all, my fellow writer-in-residence and endlessly cheerful, loving, and much-loved wife, Marion Elizabeth, lightened the burden by creating a warm and placid cocoon from which to work, as well as constructive criticism softened always with a radiant smile.

Jules Witcover

Contents

Do not run a campaign that would embarrass your mother

Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia, 1987

The hardest thing about any political campaign is how to win without proving that you are unworthy of winning.

Governor Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, Democratic presidential nominee, 1956

The voters have spokenthe bastards.

Representative Morris K. Udall of Arizona, after losing the Democratic presidential primary in New Hampshire, 1976

For all the confusion and frustration over the manner in which the election of 2000 ended, it did serve the useful purpose of demonstrating why the system in place is no way to pick a president. The chaos caused by the failure of the popular-vote winner, Vice President A1 Gore, to achieve a majority of the Electoral College on election night, and the eventual election of the popular-vote loser, Texas Governor George W. Bush, produced the accident waiting to happen described in the hardcover edition of this book, which was published on the eve of the 2000 presidential campaign.

The spectacle of the choice of the next president ultimately being made not at the polling booth but by five justices of the United States Supreme Court raised allegations of political partisanship that, in the dissenting words of Justice John Paul Stevens, can only lend credence to the most cynical appraisal of the work of judges throughout the land. Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of [the] presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nations confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.

This blow to the credibility of the judiciary, as well as public confusion and displeasure over a candidate who is the popular choice failing to become president, has rekindled calls for basic election reform. From New Yorks newly elected senator, Hillary Rodham Clinton, to the man and woman in the street, demands are being heard for dismantling the Electoral College and putting presidential selection directly into the hands of the voters with a straight national popular vote. But the resistance of smaller state politicians, protective of the greater influence the Electoral College system bestows on their constituencies, impedes the chances that it will happen.

Less drastic solutions are being discussed, such as states adopting the method of Maine and Nebraska, whereby electors are chosen by congressional district rather than statewide, and awarded on a winner-takes-all basis. Another proposal is to allocate electoral votes on a proportional basis according to the statewide popular vote. Both of these ideas might overcome or mitigate the concern of those who fear abolishing the Electoral College would remove any incentive for presidential candidates to campaign in the smaller states. But neither would guarantee that the candidate most voters said they wanted as the next president would get the job.

Still another idea that merits consideration, if the Electoral College cannot be abolished outright, is to keep it symbolically, eliminating the actual appointment of electors and awarding a bonus of 102 electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote. A Twentieth Century Fund task force examined the scheme in 1978 and concluded that the bonus would almost certainly assure the election of the popular-vote winner. The simplicity of the idea recommends it. But Republicans in Congress and in the states, aware that the Electoral College snatched victory for Bush from the jaws of popular-vote defeatwith the major assistance of the Supreme Court, supposedly above politicsmight understandably be unwilling to see its demise.