2019 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ISBN 978-1-60635-380-6

Manufactured in the United States of America

All photos are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced, in any manner whatsoever, without written permission from the Publisher, except in the case of short quotations in critical reviews or articles.

Cataloging information for this title is available at the Library of Congress.

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

The Changing Role of Presidential Contestants

in the Nineteenth Century

In the summer of 1888, Benjamin Harrison ran the first large-scale front porch campaign for the presidency from his home in Indianapolis, Indiana. The city of just over 32,000 saw more than 350,000 visitors, to whom Harrison delivered ninety-four speeches. The throngs came from all over the country by train and marched in colorful, exciting processions through town. Visitors were met by enthusiastic local crowds who joined them in backing the Republican candidate. When the delegations arrived at his home, a leader of the group would give a vetted speech and introduce Harrison. He would then greet the crowd, say something ingratiating about their history, and give issue-oriented speeches concerning tariff schedules, economic prosperity, and foreign policy. Following one of these virtuoso performances, the Pittsburgh Dispatch wrote something illuminating that the Indianapolis Journal later reprinted. The sheet pointed out that several recent presidential candidates had toured for the presidency and that Harrisons speeches were in good taste. He scrupulously refrains from personalities. He fully comprehends the significance of the great issue at stakeprotectionand rarely neglects to drive it home to the minds and consciences of his listeners. His style is plain and familiar, but his evident sincerity and wide acquaintance with the subject in hand give him an advantage possessed by few public speakers. He commands respect even when he fails to convince. The paper described

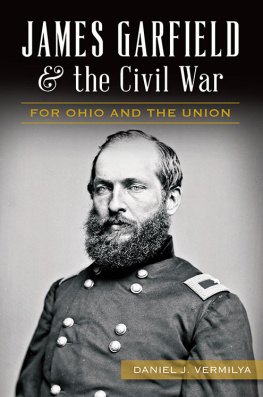

The Dispatchs assessment of Harrisons performance sheds light on the effectiveness of front porch campaigning for the presidency. Four Republicans tried the technique for the duration of their campaigns between 1880 and 1920: James Garfield in 1880, Harrison in 1888, William McKinley in 1896, and Warren Harding in 1920. They went undefeated. Front porch campaigning became popular at a time in presidential campaign history when actively seeking the office had not been effective. Candidates who went on speaking engagements had only been successful one time after five tours for the presidency between 1840 and 1872.

The Founding Fathers negative impression of seeking office seemed to loom over the campaign process during the nineteenth century. The first generation of American leaders lived out the adage, the office seeks the man, not the other way around. Common thought held that stumping made candidates seem too aggressive, too interested in the office, and prone to the problems accompanying travel, such as poorly screened appearances and rowdy locals. In 1852 a canon malfunction killed a soldier while Winfield Scott was being introduced in Columbus, Ohio, during his tour as a Whig candidate. Eight years later a rally for Democrat Stephen Douglas in New York City turned into a food fight. It also exposed candidates to unvetted moments and saw them give extemporaneous speeches that sometimes went wrong. In 1872 Democrat Horace Greeley lost his dignity by angering all of his audiences during his talkswhether they were northern or southern, black or white. By the 1880s candidates such as Garfield and Harrison did not want to seem disinterested in running, but they also did not want to come across as aggressive or unseemly. Front porch campaigning allowed them to connect with voters, make prepared statements that would be reprinted in newspapers across the country the next day, and maintain their dignity as candidates at a time when acceptable activity for a presidential contestant was a matter of debate. When the Dispatch described Harrisons style with such phrases as commands respect, good taste, scrupulously refrains from personalities, style is plain and familiar, evident sincerity, and full-fledged statesman, that was exactly what his handlers desired. Campaigning from the porch allowed him to appear interested in the office but not aggressively so. In its heyday, talking from the front porch proved to be a happy medium between aggressively stumping for the presidency and doing nothing to seek it. The strategy was also effective: no presidential candidate ever lost running from his porch.

Candidates who seemed sincere, plain, and familiar during the industrial era were accomplishing an important feat. Americans were seeing traditional, rural ideals give way to new, urban ideals as urbanization and demographic shifts served as natural outgrowths of industrialization. The process challenged almost every social norm, from the types of jobs available to workers to the ways that families functioned. Front porch campaigning allowed candidates to more actively run without breaking too far away from social and political customs. As the process unfolded, Republicans espoused a high tariff schedule to protect US factories, businesses, homes, and families; the position fit neatly with the delivery of their speeches from their homes. Industrialization catalyzed something called impersonalization, in which workers and consumers had less individual contact with their bosses and storeownersyet here were three presidential candidates willing to meet these same workers and consumers, give them a face-to-face talk from their porch, shake hands, and allow them to meet their families. Additionally, all four candidates were from Ohio, which gave them a more authentic, midwestern feel for visitors from the surrounding region.

Not only did front porch campaigning produce personable, somewhat active campaigns, but they also highlighted the vibrancy of several small, isolated, island communities in both Indiana and Ohio as the Midwest was being changed by industrialization. Mentor, Indianapolis, Canton, and Marion all provided a comfortable Middle America feel for visitors and served as a positive breath of rural America for many experiencing the downside of economic transformation. From the 1870s to the 1920s, many communities in the United States saw a dramatic shift in their value systems because of problems related to industrialization. Systems rooted in rural, agricultural, small-town values were giving away to systems couched in urban-oriented, bureaucratically minded, middle-class values. Front porch campaigns, particularly in 1888 and 1896, allowed two midwestern island communities to showcase themselves and show other island communities that they could still thrive. The process also saw growth throughout the Gilded Age. In 1880 Mentor, Ohio, only saw a few thousand visitors as front porch campaigning was still in its embryonic phase. Eight years later porch campaigning boomed as Indianapolis saw several hundred thousand visitors. In 1896 the process reached its apex in Canton, Ohio, when 750,000 people descended upon the small city. Finally, in 1920, Marion, Ohio, saw at least 250,000 visitors. The campaigns turned these relatively small communities into booming, thriving, exciting places whose extensive downtown areas offered further attractions