PART I

INTRODUCTION

Table of Contents

CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

IN ALABAMA

CHAPTER I

Table of Contents

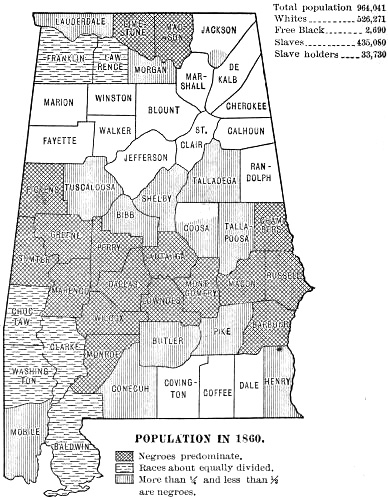

THE PERIOD OF SECTIONAL CONTROVERSY

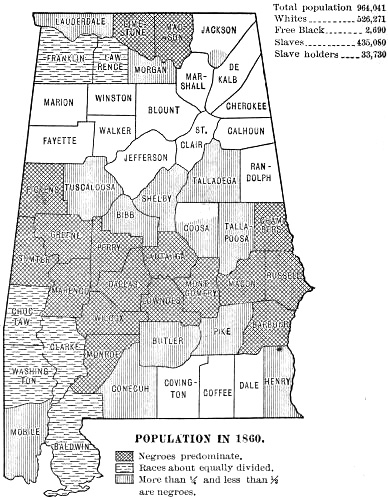

When Alabama seceded in 1861, it had been in existence as a political organization less than half a century, but in many respects its institutions and customs were as old as European America. The white population was almost purely Anglo-American. The early settlements had been made on the coast near Mobile, and from thence had extended up the Alabama, Tombigbee, and Warrior rivers. In the northern part the Tennessee valley was early settled, and later, in the eastern part, the Coosa valley. After the river valleys, the prairie lands in central Alabama were peopled, and finally the poorer lands of the southeast and the hills south of the Tennessee valley. The bulk of the population before 1861 was of Georgian birth or descent, the settlers having come from middle Georgia, which had been peopled from the hills of Virginia. Georgians came into the Tennessee valley early in the nineteenth century. The Creek reservation prevented immigration into eastern Alabama before the thirties, but the Georgians went around and settled southeast Alabama along the line of the old Federal road. When the Creek Indians consented to migrate, it was found that the Georgians were already in possession of the countrymore than 20,000 strong, and a government was at once erected over the Indian counties. People from Georgia also came down the Coosa valley to central Alabama. The Virginians went to the western Black Belt, to the Tennessee valley, and to central Alabama. North Carolina sent thousands of her citizens down through the Tennessee valley and thence across country to the Tombigbee valley and western Alabama; others came through Georgia and followed the routes of Georgia migration. South Carolinians swarmed into the southern, central, and western counties, and a goodly number settled in the Tennessee valley. Tennessee furnished a large proportion of the settlers to the Tennessee valley, to the hill counties south of the Tennessee, and to the valleys in central and western Alabama. Among the immigrants from Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee was a large Scotch-Irish element, and with the Tennesseeans came a sprinkling of Kentuckians. In western Alabama were a few thousand Mississippians, and into southeast Alabama a few hundred settlers came from Florida. From the northern states came several thousand, principally New England business men. The foreign element was insignificantthe Irish being most numerous, with a few hundred each of Germans, English, French, and Scotch. In Mobile and Marengo counties there was a slight admixture of French blood in the population.[1]

Larger Image

In regard to the character of the settlers it has been said that the Virginians were the least practical and the Georgians the most so, while the North Carolinians were a happy medium. The Georgians were noted for their stubborn persistence, and they usually succeeded in whatever they undertook. The Virginians liked a leisurely planters life with abundant social pleasures. The Tennesseeans and Kentuckians were hardly distinguishable from the Virginians and Carolinians, to whom they were closely related. The northern professional and business men exercised an influence more than commensurate with their numbers, being, in a way, picked men. Neither the Georgians nor the Virginians were assertive office-seekers, but the Carolinians liked to hold office, and the politics of the state were moulded by the South Carolinians and Georgians. All were naturally inclined to favor a weak federal administration and a strong state government with much liberty of the individual. The theories of Patrick Henry, Jefferson, and Calhoun, not those of Washington and John Marshall, formed the political creed of the Alabamians.

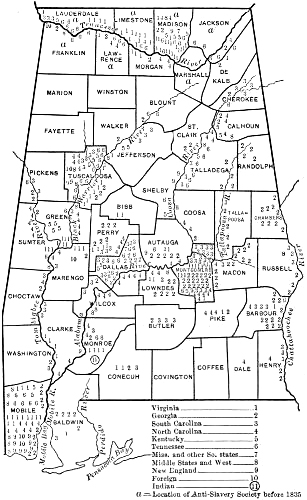

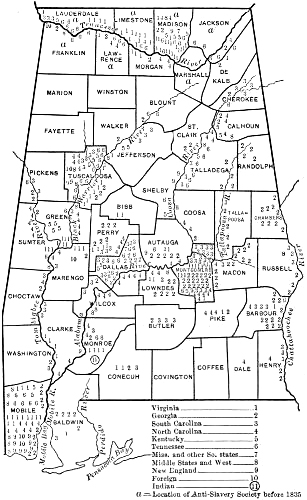

NATIVITY OF PUBLIC MEN

Larger Image

Each figure represents some person who became prominent before 1865, and indicates his native state. The location of the figure on the map indicates his place of residence. Note the segregation along the rivers and the Black Belt.

The wealthy people were found in the Tennessee valley, in the Black Belt extending across the centre of the state, and in Mobile, the one large town. They were (except a few of the Mobilians) all slaveholders. The poorer white people went to the less fertile districts of north and southeast Alabama, where land was cheap, preferring to work their own poor farms rather than to work for some one else on better land. But nearly every slave county had its colony of poorer whites, who were invariably settled on the least fertile soils. Among these settlers there was a certain dislike of slavery, because they believed that, were it not for the negro, the whites might themselves live on the fertile lands. Yet they were not in favor of emancipation in any form, unless the negro could be gotten entirely out of the waya free negro being to them an abomination. If the negro must stay, then they preferred slavery to continue.

Over the greater part of Alabama there were no class distinctions before 1860; the state was too young. In the wilderness classes had fused and the successful men were often those never heard of in the older states. A candidate of the plain people was always elected, because all were frontier people. This does not mean that in Huntsville, Montgomery, Greensboro, and Mobile there were not the beginnings of an aristocracy based on education, wealth, and family descent. But these were very small spots on the map of Alabama, and there were no heartburnings over social inequalities.[2]

Such was the composition of the white population of Alabama before 1860. No matter what might be their political affiliations, in practice nearly all were Democrats of the Jeffersonian school, believing in the largest possible liberty for the individual and in local management of all local affairs, and to the frontier Democrat nearly all questions that concerned him were local. The political leaders excepted, the majority of the population knew little and cared less about the Federal government except when it endeavored to restrain or check them in their course of conquest and expansion in the wilderness. The relations of the people of Alabama with the Federal government were such as to confirm and strengthen them in their local attachments and sectional politics. The controversies that arose in regard to the removal of the Indians, and over the public lands, nullification, slavery, and western expansion, prevented the growth of attachment to the Federal government, and tended to develop a southern rather than a continental nationality. The state came into the Union when the sections were engaged in angry debate over the Missouri Compromise measures, and its attitude in Federal politics was determined from the beginning. The next most serious controversy with the Federal government and with the North was in regard to the removal of the Indians from the southern states. The southwestern frontiersmen, like all other Anglo-Americans, had no place in their economy for the Indian, and they were determined that he should not stand in their way.