Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

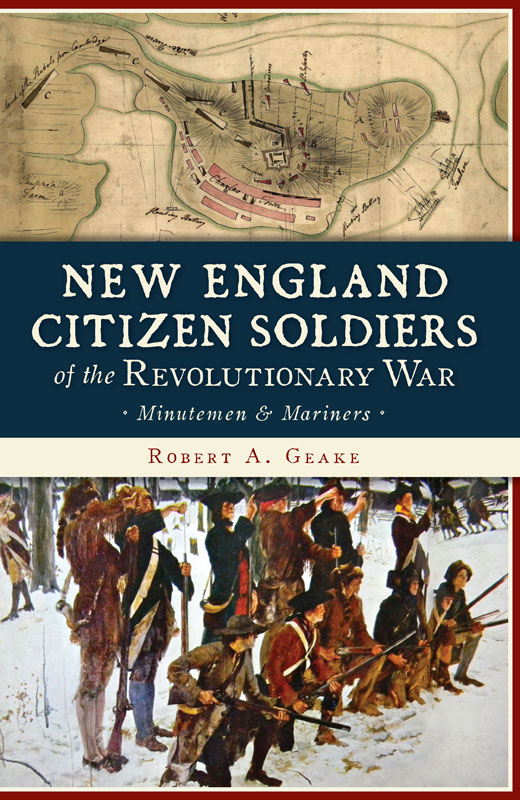

Copyright 2019 by Robert A. Geake

All rights reserved

First published 2019

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.833.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019945081

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.260.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

I n John Millers influential work Origins of the American Revolution, we find the opinion that the English in waging war on North America generally overlooked what proved to be one of Americas most serious weaknesses during the War of Independence: the conviction that the militia were the guardians of liberty and that a regular standing army was its eternal enemy.

This belief was indeed widespread, not limited to rural areas, where there was no debate whatsoever, but also in the urban centers of America. The motto beneath the banner of Bostons Continental Weekly and Adviser in 1778 read, The Entire Propriety of Every State Depends Upon the Discipline of its Armies. The quote, attributed to the king of Prussia, may well have been intended to mean the nation state, but Americans thought differently, and even into the war that united those separate armies into one cause, the concerns of each state were sometimes placed above any notion of allegiance to the idea of one nation.

The contributions of the militia to the American Revolution are irrefutable but often misunderstoodfrom the mythology grown from the minutemen to the mistrust and grumbling from Washington and other officers as they tried to make these bands of independent men conform to the standards of a standing army to the guerrilla tactics that unnerved the enemy and underscored the American victory.

Their influence on the public imagining of the war would ensure that independent militias would remain the citizen soldiers of their communities. The young men who enlisted to serve in the local militia were often taking an opportunity to gain status in their communities, as this book will show.

For many historians and readers of military history, there is a distinct difference between the regulars, or enlisted men of the Continental army, and the militia, composed of men who served part time in local companies. These men were mostly entrusted with protecting their communities and aiding with supplies during the war but were also frequently called on to march to a neighboring colony/state to shore up defenses thereor march into battle when Washington assembled troops for a major campaign.

The first Continental army assembled began with conscripts from those same local militiasthe officers first and then those men who passed the age and physical requirements to serve. It is important to note again that the states/colonies had no standing army, and the majority of Americans held the view that a standing army was anathema to democracy. Of the many written opinions on the issue from that time, perhaps Samuel Adams in writing to his friend James Warren expressed their reasons most succinctly:

[A] standing army, however necessary it may be at some times, is always dangerous to the liberties of the people. Soldiers are apt to consider themselves as a body distinct from the rest of the citizens. They have their arms always in their hands. Their rules and their discipline is severe. They soon become attached to their officers and disposed to yield implicit obedience to their commands. Such a power should be watched with a jealous eye.

The Articles of Confederation, the precursor to our Constitution, authorized Congress only to assemble a navy and only referenced those land forces that would be gathered by the states from their militia and other enlisted citizens.

Many of those who enlisted in the Continental army served their nine-month terms and returned home, sometimes keeping active in local defense and other times reenlisting in the army after several months absent. Militiamen drilled on a regular basis and were called on alarm to serve for times that varied from a week to several months.

The very idea of Congress holding any military power brought a flurry of proposals to limit any such authority from representatives of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Connecticut. While Washington had envisioned the army and militia as having a separate but mutually supportive role to play in the war effort, those hopes became only partially realized. When the general requested a draft in December 1776, he was rebuffed, and the matter of enlistments was passed along to the states/colonies.

While Congress approved Washingtons recommendations as to the size and organization of the state militias, each state/colony struggled to fulfill its quota during the war, and often men served both at home and abroad. In so doing, the lines between those who served in state militias and the Continental army continued to overlap and sometimes blurred the lines between identification as a regular or militia.

As historian Don Higginbotham described, Fear of American militarism, of a real standing army, increased with the lengthening of the war: Congress soon found it incumbent to re-enlist men for three years, or the duration of the warmanpower shortages resulted in the Continental Armys bearing a growing resemblance to classic European armies. Criminals, British deserters, servants, drifters and the like were taken into service as Congress scraped the bottom of the barrel of human resources.

Regardless of their origin (enlisted or drafted), those who served in militia or as privateers were all citizen soldiers who served and contributed, no matter whether at home or far from their farms and families, and played their part in winning the American War of Independence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

M y sincere thanks to the librarians at the Rhode Island Historical Societys Robinson Research Center, particularly Jennifer Galpern and Michelle Chiles, who assisted me in navigating the large collection of Revolutionary War papers in the collections.

I would also like to acknowledge information gathered from Historic New England, the Warwick Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the John Carter Brown and John Hay Libraries at Brown University and the archives of the Cocumscussoc Association and the James Mitchell Varnum Museum.

Thanks must also be given to Norman Desmarais, professor emeritus of Providence College; Patrick Donovan, curator of the Varnum Museum; David Matthew Proccacini, director of the Nathanael Greene Homestead; Brian Mack, director of the Fort Plain Museum; historian James F. Morrison; Mike Kinsella of The History Press, as well as my editor, Ryan Finn; and to Christian McBurney, who has served as a mentor in my ventures into writing of the Revolutionary War.

![Stephen Ambrose - Citizen Soldiers [Condensed]](/uploads/posts/book/457593/thumbs/stephen-ambrose-citizen-soldiers-condensed.jpg)