Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by Robert A. Geake

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978.1.62584.704.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Geake, Robert A.

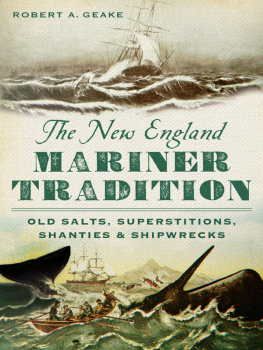

The New England mariner tradition : old salts, superstitions, shanties and shipwrecks / Robert A. Geake.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-228-7

1. Sailors--New England--History 2. Seafaring life--New England--History. 3. Legends--New England--History. 4. Manners and customs. 5. Folklore--New England--History. I. Title.

F4.G43 2013

398.20974--dc23

2013039006

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my ancestor First Mate Nicholas Easton, originally from Newport, who was lost at sea in 1828 off the Cape of Good Hope while aboard the whaling ship Zone, at the age of thirty-two.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Impacable I, the old implacable Sea:

implacable most when I smile serene-

Pleased, not appeased by myriad wrecks in me

Herman Melville, Pebbles

My efforts to understand the adventures and lives of the mariners of New England began with reading Melville. Not with the momentous Moby Dick, as you may already have surmised, but with the lesser work White Jacket, which gave a glimpse into life on an American naval ship in the early nineteenth century. It was a rigid, confining and often violent world these sailors lived in, and it prepared me for reading Moby Dick the following year. I wallowed slowly through the book like the proverbial drunken sailor, utterly intoxicated by the story and the world that was presented to me at fourteen. Even though I was reading Melvilles masterpiece 120 years after its publication, living in New England with the ocean and the historical architecture from that era all around, I felt a distinct connection to his story.

As an adult, Ive continued learning of the mariners life, mainly from reading those historians mentioned throughout this book. Anyone wanting to learn more of New Englands mariners should reference the bibliography, where those historians to whom I am indebted, and their books, are duly noted.

I want to thank the staff of the John Carter Brown Library for their assistance in finding needed books and materials, as well as the staff of the John Hay Library for their assistance in navigating their fine Whaling Collection. Thanks must also go to Henry A.L. Brown for his astonishing collection of Rhode Island ephemera as well as his personal knowledge of Rhode Islands shoreline and the lifesaving stations of the coast. The New Bedford Whaling Museum and Library were helpful in providing both physical and digital logbooks for my research, and the Special Collections Department of the Providence Public Library, which has an unparalleled collection of whaling logbooks, records and memorabilia in the state, is a valuable resource for any researcher.

Introduction

In the winter of 177980, young merchant seaman Charles Carroll, working on his fathers ship, the Family Trader, on a voyage to Guadalupe, recorded in his journal that on December 2, 1779, Mr. Tropic Man paid us a visit in a very frightful dress. Had a demand of Mr. Taylor passenger of whom he received a case bottle gin.

On the ships return voyage to South Carolina a month later, Carroll and the crew found themselves in the path of another squall. On January 7, 1780, he recorded, Today also, the wind very Hard with Seas mountain Higha Consultation held to Conclude Whether we should beat about Hereor to return to the West Indies for water and provisions. It was unanimously agreed to Waite hereto see what the Almighty would decreeKept Centry in the cabin tonight as we were very suspicious of 6 or 7 in our crews rising and taking the vessel or at Least doing a deal of mischief.

These two passages highlight only a small part of what any seaman working on naval, merchant, whaling, privateering or slaving ships faced on each voyage into the Atlantic and beyond. During any cruise, potentially fatal storms, low provisions, disease, violence among the crew and the practice of old superstitions, such as the offering of a case bottle gin to appease Neptune and save the ship and crew, could be expected to be encountered. Many were the causes of death at sea.

In this book, I want to explore the preparations seamen made for voyages with their own mortality in mind, the rituals practiced onboard for the crews safety and those after tragedy struck and the remembrance of these captains and crew members onboard ship and at home in their various forms. In this way, I hope to touch on some forgotten traditions among these mariners in the age of sail and to recover, as well, a glimpse into their lives on the sea and at home, where family members waited for their return.

By the end of the seventeenth century, there had been a long-established brotherhood among seamen of many races in the Atlantic trade. The journal of Edward Barlow, the son of an English farmer whose descriptions and accounts of life at sea cover over forty years of voyages, gives such a glimpse into these early practices and presents a stark truth of circumstance that would prove to be the great factor in the gathering of crews from the port cities of both England and the Colonies. He writes, In the later end of April in the year 1675, I began to prepare myself for another voyage to sea, for my money would not hold outand having no other calling but the sea to get my livelihood by, I must go, yet I wished many times that I had a trade, so that I may have got my living ashore when I had been weary of the sea, but for that I had nobody to blame but my own foolish fancy.

Marcus Rediker wrote that the high mortality rate and the rigors of maritime work made seafaring a young mans occupation and culture, and while it was true, as the historian concluded, that most seamen were between twenty and forty years of age, some, like Barlow, were destined to become old salts.

Barlow saw this life ahead as a great grief for an aged man and wrote gloomily of the fate he saw for himself and others, to be little more than a slave, being always in need, and enduring all manner of misery and hardship, going with many a hungry belly and wet back.

Of course, longevity was a rarity among seamen, for they seldom live until they be old, Barlow wrote. They either die with want or with grief to see themselves so little regarded.

Life at sea for the ordinary and able-bodied seamen was an extreme hardship, and while much was made of the toughness of Jack Tar in the lore and literature that appeared during the age of sail, these sons, husbands and fathers who toiled aboard ships left remarkable legacies of love of family in letters, in song and in poignant scenes scrimshawed on ivory. They lived and worked always under the dark cloud of knowing that death could come at any moment.

Next page