Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2021, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-4693-9

ISBN 10: 0-8229-4693-9

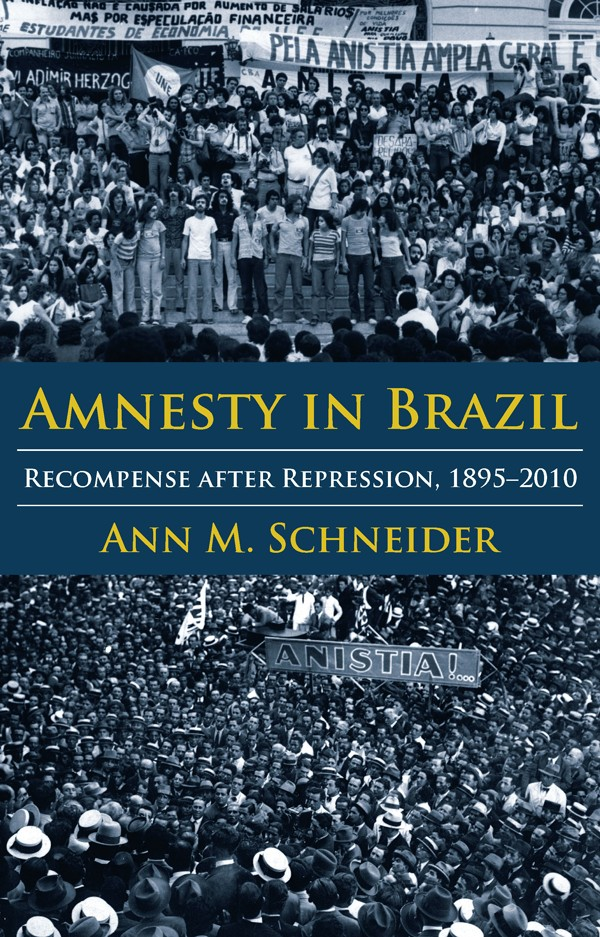

Cover art: Photographs of political rallies in downtown Rio de Janeiro in 1979 (top), courtesy of the National Archive, and 1929 (bottom), courtesy of CPDOC/FGV.

Cover design: Melissa Dias-Mandoly

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8852-6 (electronic)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Researching and writing this book has been a labor of love that stretched over many years. For long spells since concluding its first draft in the form of a dissertation I had to set the project aside. The stories, however, would not let me go. As circumstances allowed, I returned to them to conduct further research and to puzzle over their broader significance and connections. Even when I was not actively working on the project, it was never far from my mind. But it is not mine alone. The actual completion of the book depended on the support, generosity, and inspiration of many. Not everyone who mattered in getting this to the finish line is mentioned by name below, but you know who you are, and I do too. Thank you!

The evolution of my dissertation into this book ran parallel to a now decade-long career as a forensic historian conducting research in support of human rights accountability work. This work has immersed me into the histories of countries throughout Latin America and given me opportunities to think comparatively about processes of reckoning with legacies of state-sponsored abuses. In addition to these more macro-level considerations, I have been privileged to meet and collaborate with a number of human rights scholars, defenders, and entrepreneurs whose work has led to innovations in human rights accountability throughout the region. I have also spent countless hours listening to the testimony of survivors, often over time and space, but sometimes face-to-face. I carry all of their stories with me too. They shape how I think about historical narratives, especially the stakes in centering individual experiences.

I would not have been able to complete the research for this book without generous financial support. A recent Fulbright Scholars Program grant allowed me to spend two consecutive summers doing additional archival work, including in collections that did not exist when I wrote my dissertation. I have not forgotten that I was able to accept the grant because of truly wonderful colleagues who made it easy for me to step away and very nice to return. During my doctoral program, a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship, together with a Social Science Research Council International Dissertation Research Fellowship, gave me the chance to live and study extensively in Brazil. Grants from the Tinker Foundation, the Mellon Fellowship in Latin American History, and the University of Chicagos Center for Latin American Studies and History Department funded additional short-term research trips.

My very first academic trip to Brazil in 2003 was in the form of a human rights internship supported by the University of Chicagos Center for Human Rights (now the Pozen Family Center for Human Rights). At that time, it was the only such center not housed in a law school and with a vision for and support of human rights work in the social sciences and humanities. In addition to the summer funding, the center provided students like me with year-round opportunities to make connections between scholarship and practice, including through the example of its then director, Susan Gzesh. I spent my internship assisting with cataloguing the archive of Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais, an advocacy organization in Rio de Janeiro. It was there that I began to see, or to see differently, some of the stakes in and complexities behind forms of reckoning with repression in Brazil. It was also there that I first learned a bit about the life story of Victria Grabois, which was one among those that would not let me go.

Before I was a graduate student, I was a high school Spanish teacher with an inclination to teach through topics in the news. In 1998, I watched unfold in real time the events surrounding the arrest in London, on a Spanish warrant, of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. It was another story that grabbed hold of me, so much so that I decided to go to graduate school with an idea of working in human rights in Latin America. In the M.A. program at the University of Texas, Seth Garfield got me to think about the discipline of history and about Brazil. At the University of Chicago, Dain Borges taught me to be a historian of Brazil. For my dissertation, he urged me to think beyond the more recent past, and to interrogate and analyze the role and impact of amnesty over time. Also at the University of Chicago, Ana Lima tailored her Portuguese classes to the respective needs of her students, assigning just the right works of literature to complement and inform our research projects. Many of the literature works cited here I first read in her classes.

I likewise extend my gratitude to fellow graduate students whose examples, insights, and friendships, then and now, not only deepen my appreciation and love of the study of history but of those who pursue it. Among them, special thanks go to Patricia Acerbi, Pablo Ben, Julia Brookins, Nancy Buenger, Jessica Graham, Miranda Johnson, Sarah Osten, Jaime Pensado, Dora Sanchez-Hildalgo, Rosa Williams, and Julia Young.

In the intervening years, a number of scholars have provided advice and support for this project, as well as thoughtful comments and feedback on portions of the manuscript. I am especially grateful to Rebecca Atencio, David Fleischer, James Green, Mariana Joffily, Glenda Mezarobba, Carla Rodeghero, Nina Schneider, and Marcelo Torelly. The careful reading and incisive comments of the anonymous reviewers for the University of Pittsburgh Press improved my thinking and the manuscript.

The manuscript came together in the way that it did because of the expert advice and assistance of archivists and librarians, especially in Rio de Janeiro and Braslia, who helped me find my way to a wealth of material on the adjudication of amnesty. It also depended on the generosity of many anistiados themselves who shared their stories with me. Among them, I will make special mention of Victria Grabois and the late Mrio Lima whose personal experiences with amnesty are told here. I also wish to thank the many other members of Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais and other former Reduc refinery workers who likewise were generous with their time and in the telling of their stories and who similarly informed this book.

My heartfelt gratitude goes to both my American and Brazilian families, who seemed to know when to ask about the book and when to refrain from doing so. I thank my parents for giving space to my early signs of wanderlust and support throughout the sojourns that followed. I thank my Brazilian family precisely for making me part of the family and always right at home.

Before closing, I want to remember Sarah Peckham, who had much to do with me taking the first steps on the path that has led me here. She would be so pleased.

The final acknowledgment rightly goes to Ricardo, Oliver, and Margot, whoin that ordercame into my life and made it just as it should be. They have had to share my attention with this project for too long, may they now share in the satisfaction of its completion and the knowledge that, above all, I hope it makes them proud.