The Civil War in the West has a single goal: to promote historical writing about the war in the western states and territories. It focuses most particularly on the Trans-Mississippi theater, which consisted of Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, most of Louisiana (west of the Mississippi River), Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma), and Arizona Territory (two-fifths of modern day Arizona and New Mexico) but encompasses adjacent states, such as Kansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, that directly influenced the Trans-Mississippi war. It is a wide swath, to be sure, but one too often ignored by historians and, consequently, too little understood and appreciated.

Topically, the series embraces all aspects of the wartime story. Military history in its many guises, from the strategies of generals to the daily lives of common soldiers, forms an important part of that story, but so, too, do the numerous and complex political, economic, social, and diplomatic dimensions of the war. The series also provides a variety of perspectives on these topics. Most importantly, it offers the best in modern scholarship, with thoughtful, challenging monographs. Secondly, it presents new editions of important books that have gone out of print. And thirdly, it premieres expertly edited correspondence, diaries, reminiscences, and other writings by participants in the war.

It is a formidable challenge, but by focusing on some of the least familiar dimensions of the conflict, The Civil War in the West significantly broadens our understanding of the nations most pivotal and dramatic story.

Nothing brings the Civil War to life as much as a letter or diary written by a participant in the struggle. Students of the war are doubly blessed in this sense, first, because the Civil War generation wrote so often about their wartime experiences and, second, because later generations treasured and preserved those invaluable documents. The trick, always, has been to make their writings available to the public. Scholars spend much of their time trawling archival collections around the country, but even they, and certainly general readers, can benefit from the publication of obscure, rare, or otherwise hard to obtain documents, such as those still in private hands.

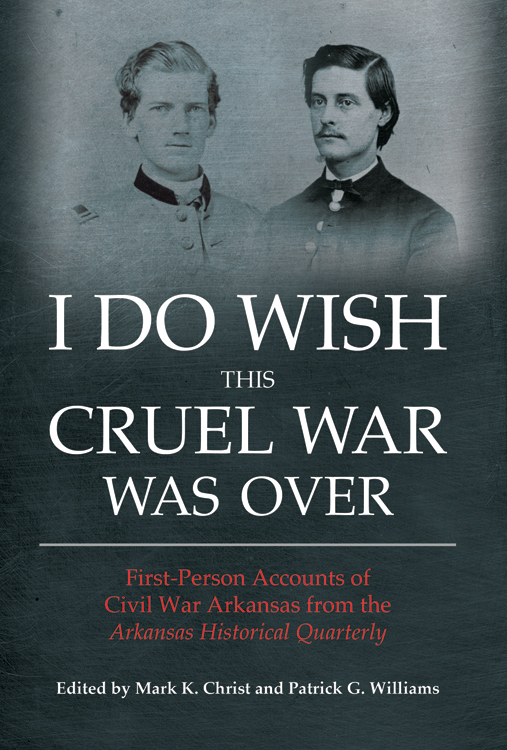

A traditional solution to this problem of access has been for historical journals to publish firsthand accounts of the war, and among the most consistent contributors to this literature has been the Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Since 1942, when it was founded, the AHQ has made a point of publishing superbly edited and annotated documents pertaining to the states history, and no era has received more attention than the Civil War years. Editors Mark K. Christ and Patrick G. Williams have selected the most revealing, incisive, and memorable of those documents from the past seventy years.

No one could ask for better interpreters of this material than Christ, the director of community outreach for the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, and Williams, the current editor of the AHQ. They are among the premier scholars of Arkansas history, and Christ, in particular, has published extensively on the Civil War. Beginning with Arkansass belated decision to join the Confederacy in May 1861, they guide readers through the entire conflict. The initial excitement about Confederate independence, the rush of men to enlist, the major military campaigns, as well as the political divisions between neighbors, the horrors of the guerrilla war, the rise and fall of public confidence in the Confederacy, all of this and more is explored through the words of the soldiers and civilians who experienced the upheaval of war.

Besides the convenience of having so many and such varied accounts brought together in a single volume, the opportunity to read these letters and diaries as a continuum, as part of a single story, is a rare treat. As one moves from one narrative to the next, sharing the perspectives of scores of different people, the scope and drama of the war, even in such a relatively small space as Arkansas, is inescapable. We are reminded yet again of the Civil Wars enduring hold on our imagination.

Daniel E. Sutherland

T. Michael Parrish

Series Editors

The Arkansas Historical Quarterly began life in the early, dark days of World War Two and from the beginning devoted many of its pages to an earlier, equally grim conflictthe American Civil War. Since 1942, in addition to fine scholarship on the war in Arkansas, the Quarterly has published dozens of edited and annotated period documentsletters, excerpts from diaries, and memoirs of soldiers fighting on either side in the state, the civilians caught between them, and the homefolk awaiting their return. A good sampling of this testimony is gathered here, arranged so as to create a sort of first-person narrative of the Civil War in Arkansas.

These documents nicely advertise the value of this sort of primary material. The firsthand, ground-level perspective surely offers a more immediate sense of the wars horrors, its mundane hardships, its languid stretches, and its moments of frivolityeven hilaritythan one finds in sober scholarly accounts dispatched from the ivy towers or the Olympian heights. And these documents can tell us about more than just the war. Students of American culture have suggested that the volubility of this letter-writing, diary-keeping generation, when combined with its often imperfect grammar and phonetic spelling (new money, for instance, lands one of our Arkansas soldiers in the horse pittle), might give us as close an approximation as we are likely to get of the mid-nineteenth-century spoken word.

The accounts collected here are valuable, though, for more than the immediacy of their language and observation. In many cases they address aspects of the war that would become objects of scholarly and popular fascination only years after the documents initial appearance in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly. These items, for instance, show Arkansas to be anything but a sideshow long before many historians woke up to the war west of the Mississippi River. Guerrillas populate these letters, diaries, and memoirs, anticipating Daniel Sutherlands point that such irregular combat, rather than armies behaving in the fashion prescribed at West Point, constituted the real war in Arkansas. That both sides waged a hard war against civilians long before William Tecumseh Sherman set foot in Georgia is fully revealed in the breathtaking nonchalance with which a number of our correspondents refer to towns beingor having beenburned and homes plundered. This hard war, along with the happier fact that men sometimes served in units so close by as to make visits home practical, kept wives, mothers, and sisters (whether Virginia Davis Gray of Princeton, Arkansas, or Frances Gilliam of Paraclifta) in close quarters with the conflict. These documents, then, place women at the center of the Civil War long before talented historians like Stephanie McCurry and Drew Gilpin Faust did. A reader will find varying degrees of commitment in these soldiers letters and diariesfrom James Madison Bowlers showy determination to see things through to William Elisha Stokers constantly being on the verge of skedaddling. Perhaps this collection might finally convince readers that there can be no single answer to that much-debated question of what motive was paramount in driving young men to keep fightingcause, comrades, coercion, or the sheer difficulty of getting out once one had gotten in. The references made in these documents to African Americans gaining freedom, losing freedom, or being killed for being free simply confirms historians growing appreciation for the complexities of emancipation. Freedom was not something simply