Copyright 2015 by Bernadette Cahill

All rights reserved. Published by Butler Center Books, a division of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library System. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except for brief passages quoted within reviews, without the express written consent of Butler Center Books.

The Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Central Arkansas Library System

100 Rock Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

www.butlercenter.org

First edition: September 2015

ISBN 978-1-935106-82-1

ISBN 978-1-935106-83-8 (e-book)

Manager: Rod Lorenzen

Book and cover designer: H. K. Stewart

Copyeditor: Ali Welky

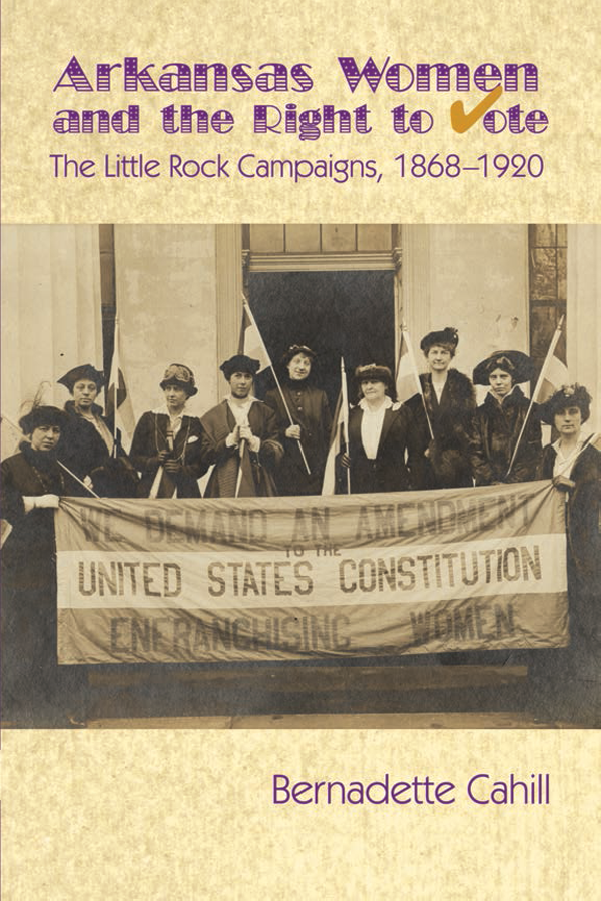

Front cover: Suffragists pose in the doorway of the Old State House in Little Rock displaying the Great Demand banner that led the 1913 inaugural suffrage campaign march in Washington DC. Mabel Vernon (fifth from left) and Alice Paul (second from right), national organizers for the Congressional Union, are shown with members of the Arkansas branch of the organization. (From left to right): Mrs. Bernard Hoskins, Mrs. Faith Jarrett, Miss Gertrude Watkins, Miss Josephine Miller, Mrs. M. Blaisdell, Miss H. Chambers, and Mrs. S. P. Scott. (Photo courtesy of Sewell-Belmont House Museum, Washington DC)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cahill, Bernadette.

Arkansas women and the right to vote : the Little Rock campaigns, 1868-1920 / Bernadette Cahill. -- First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-935106-82-1 (paperback : alkaline paper) -- ISBN 978-1-935106-84-5 (e-book)

1. Women--Suffrage--Arkansas--Little Rock--History. 2. Suffragists--Homes and haunts--Arkansas--Little Rock. 3. Suffragists--Arkansas--Little Rock--Biography. 4. Historic buildings--Arkansas--Little Rock. 5. Historic sites--Arkansas--Little Rock. 6. Little Rock (Ark.)--History. 7. Little Rock (Ark.)--Biography. 8. Little Rock (Ark.)--Politics and government. 9. Little Rock (Ark.)--Buildings, structures, etc. I. Title.

JK1911.A8C24 2015

324.6'2309767--dc23

2015017773

Printed in the United States of America

This book is printed on archival-quality paper that meets requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences, Permanence of Paper, Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Butler Center Books, the publishing division of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, was made possible by the generosity of Dora Johnson Ragsdale and John G. Ragsdale Jr.

This book is dedicated to

all the women

who

non-violently

faced down

ridicule,

discrimination

exclusion,

violence,

and

torture

in pursuit of votes for women

from the founding of the United States

to 1920.

Introduction:

A Lost Opportunity

In 1868, a proposal to include womens voting rights in Arkansass new constitution was laughed out of debate. That first attempt at womens suffrage in the state occurred at the same time as the adoption of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing citizenship and equality specifically to men of all races. It also occurred only a couple of years before the introduction of the 15th Amendment, guaranteeing all men of the nation, regardless of race, the right to vote. If in 1868 a clause giving women the vote had been included in its new constitution, Arkansas could have been called the trailblazer state, as it would have been the first state in the Union to guarantee womens equal participation in the political process.

This lost chance of setting an example for the rest of the country to follow and the opportunities thrown away by that failure are sad to contemplate. From Arkansass inauspicious start toward womens suffrage in 1868 to the successful reaching of the goal by 1920Arkansas ratified the 19th Amendment in July 1919the struggle to win equal voting rights for women took more than fifty years. During this time, countless women lived and died excluded from the political processand many who campaigned for inclusion died before their cause was finally won.

The campaign for votes for women in Arkansas, however, actually took much longer than half a century, for the agitation for womens right to vote in the state cannot be divorced from the national campaigns, which began at the Seneca Falls Convention in New York in 1848. Among the proposals produced at that convention, the most controversial was the right of women to vote. Introduced and passed at the prodding of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the demand for suffrage was that ladys

That the rights of women are considered civil rights at all tends to give people pause, for the concept of civil rights in the United States in the twenty-first century is virtually synonymous with the rights of African Americans. Yet the history of civil rights in general is much longer and broader than the movement for rights for African Americans that began in the 1950s. With regard to the vote specifically, some women questioned their exclusion at the countrys founding and early in the Republic. With the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, women launched what became a campaign to win suffrage along with many other reforms for women, such as equal education, equality under the law, and equal employment opportunity. The common denominator of all of these reforms was a protest against the inequality inherent in the segregation into public and private spheres along sex lines. Womens concerns, including the vote, therefore, arose long before the Civil War. By the time of that conflict, universal suffrage had become the call of reformers for when slavery was ended.

Before the war, universal suffrage meant all adults, regardless of race or sex. After the war, however, Republicans hijacked the term, applying it to an expanded but extremely limited ideavotes for men only. This warped definition of universal became the legislators new mantra after abolition and excluded half the population from the vote. By 1870, with the forced ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, male suffrage had become a constitutional guarantee and male-only suffrage the fundamental law of the land. At that point, the excluded fifty percent of the population faced continuing their already long-established campaign but in much worse circumstances than before. Womens exclusion from the vote had previouslybeen a matter of custom and prejudice; now it was fundamental law that had to be changed. Women, therefore, had to choose to focus on suffrage as a first step toward complete womens equality.

The notion of womens struggle for civil rights, therefore, is a matter of fact, even if it is largely ignored and usually lost in womens rights slogans. Meanwhile, womens rights have historically been relegated to a lower status than rights for others. Evidence of this is that the history of black civil rights comes to the fore both nationally and locally. For example, my research in Washington DC found that the places where African Americans fought for their civil rights in the nations capital are clearly marked and honored, complete with labels and a downloadable guide. In Arkansas, Little Rock has its Central High School National Historic Site commemorating the desegregation battles of the 1950s and 1960s, while downtown markers also denote key places where blacks fought to win equality. These historical commemorations are instructive, poignant, and rewarding to see.