First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Social History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Ann Kramer 2013

Hardback 978 1 84468 119 8

The right of Ann Kramer to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Bridlington, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Thanks are due to the following:

Angharad Tomos for allowing me to interview her about her grandfather David Thomas

Bangor University for access to documents relating to David Thomas Bexhill Museum for access to archive material relating to Henry Sargent

Felicia Shanahan for permission to reproduce material and images on Richard Porteous.

Harper Collins Publisher for help in regards to copyright for On Two Fronts, Corder Catchpool and Conscription and Conscience, John W. Graham. The publishers have made every effort to trace the authors, his estate and his agent without success and would be interested to hear from anyone who is able to provide them with this information

Independent Labour Publications (ILP) for permission to take quotes from Fenner Brockways Inside the Left

Library of the Religious Society of Friends in Britain for their help and access to their archives, John Brocklesbys memoirs and the Winchester Whisperer

Margaret Sargent for permission to reproduce drawings and photographs by Henry Sargent

Mary Brocklesby for permission to reproduce two photographs of her husband, John Brocklesby

Naomi Rumball for permission to reproduce images from Cyril Heasmans album

Peace Pledge Union (PPU) for permission to reproduce images

Every attempt has been made to contact the copyright holders of quoted materials. Should any references have been omitted, please supply details to the publisher, who will endeavour to correct the information in subsequent editions.

| CO | Conscientious Objector |

| FAU | Friends Ambulance Unit |

| FoR | Fellowship of Reconciliation |

| ILP | Independent Labour Party |

| IWM | Imperial War Museum |

| NCC | Non-Combatant Corps |

| N-CF | No-Conscription Fellowship |

| RAMC | Royal Army Medical Corps |

| UDC | Union of Democratic Control |

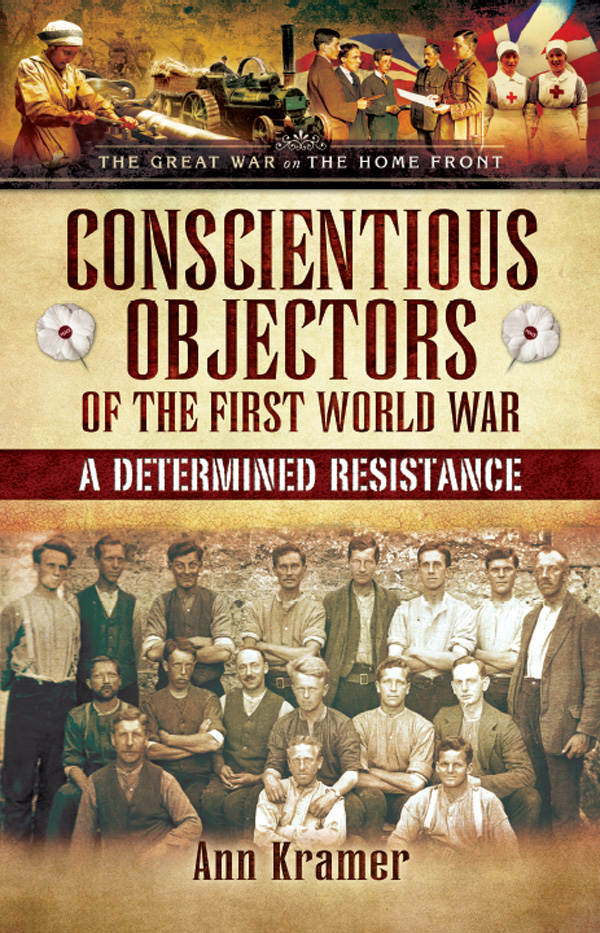

We reaffirm our determined resistance to all that is established by the Act

I n 1916 a new phrase conchies entered the English language. Used derogatively by press and public, the term referred to conscientious objectors, those men who for reasons of conscience refused to be conscripted and to pick up arms to kill their fellow men. Interestingly, quite a few conscientious objectors, possibly slightly self-mockingly, also described themselves as conchies.

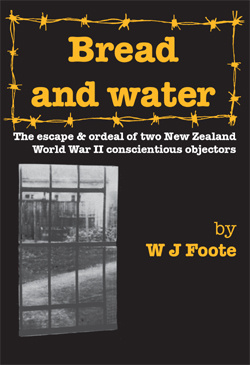

Some 16,000 men took their stand as conscientious objectors during the First World War, or at least from 1916 when, in the face of mounting and horrendous casualties in the trenches, conscription was introduced into Britain. They did so for various reasons: some were motivated by their religious beliefs, others for political or humanitarian reasons, but all believed that it was wrong to accept conscription and profoundly wrong to kill. To say the very least, their stand was not popular. They were mocked and vilified by press and public, were ostracised by friends and family, sacked from jobs, imprisoned and physically brutalised. To most people they were seen as shirkers, cowards and even traitors and they were treated accordingly. Although the Military Service Act of 1916 made allowance for conscience objection, those who took that stand were usually rejected by the tribunals set up to test their sincerity, and handed over to the army, where brutality and abuse were often the norm. In an attempt to break their resistance, some conscientious objectors were even sent to France and threatened with the death sentence. But even this did not shake the resolve of conscientious objectors. Refusing to accept military orders, they were court-martialled and sent to prison, where hundreds endured long prison sentences with hard labour, including periods of solitary confinement on a punishment diet of bread and water. Under the so-called cat and mouse procedure, hundreds were returned again and again to prison. Not all conscientious objectors took such an absolutist stand: some accepted alternative service and a few, mainly Quakers, worked with the Friends Ambulance Service, helping wounded soldiers of both sides.

Despite all the bullying, intimidation and brutality directed at conscientious objectors, nearly all of them refused to abandon their principles and give in: they maintained their resistance right through to the end of the war and beyond, believing as they did that a mans conscience takes priority over the demands of the State, no matter what the consequences. Theirs is a thrilling and inspirational story and, not surprisingly, their actions baffled representatives of the State in the army and in government.

As populations mark the hundredth anniversary of the start of the First World War, much of the attention is focused on the courageous young men who died in the trenches or those who worked on the home front but very little attention is usually paid to those men who, in the face of enormous pressure, had the courage to stand by their principles and refuse to fight. Theirs was a very determined resistance and, in contrast to the many memorials to soldiers who died in the First World War, there are hardly any memorials marking the courage and determination of the men who not only endured considerable hardship to make a conscientious stand but also died or suffered mental breakdown as a result.

Having been part of the anti-war movement since my teens, I feel it is important to try and redress the balance by telling the stories of those remarkable men who held out against the war machine of the First World War to stand as conscientious objectors. Although they were relatively few in number, their impact was far greater than might have seemed: they proved it was possible to use passive resistance to challenge the State, kept the principles of pacifism and a belief in the Brotherhood of Man alive at a time when killing was legion, and paved the way for an influential peace movement that sprang up between the two world wars and still continues today. Their bravery and determination made it possible for the next generation to take their stand as conscientious objectors between 1939 and 1945, helping to inspire not just those second-generation conscientious objectors but also war resisters ever since.