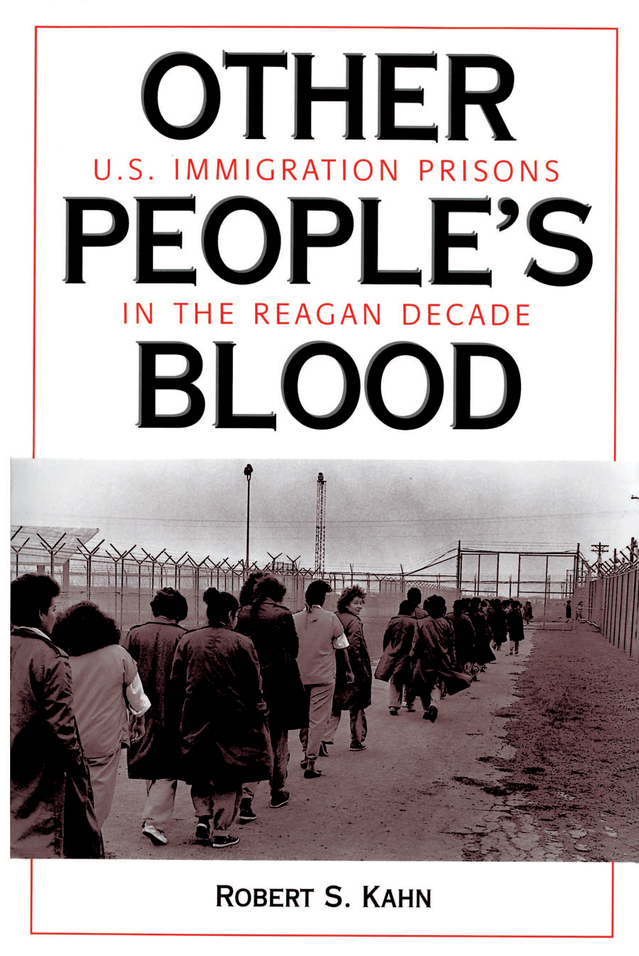

Other People's Blood

Other People's Blood

U.S. Immigration Prisons in the Reagan Decade

Robert S. Kahn

For Jennifer, Carlos, Alex, and Cecilia

First published 1996 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Kahn, Robert S.

Other peoples blood: U.S. immigration prisons in the Reagan

decade / Robert S. Kahn

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-8133-2445-9 (alk. paper). ISBN 0-8133-2446-7 (pbk.: alk.

paper)

1. RefugeesGovernment policyUnited States. 2. Immigrants

Government policyUnited States. 3. United StatesEmigration and

immigrationGovernment policy. 4. PrisonsUnited States.

5. United StatesPolitics and government19811989. I. Title.

JV6601.K35 1996

365'.4dc20 96-9119

CIP

This book was typeset by Letra Libre, 1705 Fourteenth Street, Suite 391, Boulder, CO 80302.

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-2446-3 (pbk)

Contents

Researchers have already cast much darkness on the subject, and if they continue their investigations we shall soon know nothing at all about it.

Mark Twain

There are no composite scenes, interviews, or characters in this book. Refugees who did not want to be identified have been given a name here that may or may not be their own. Thus, an interview with Jos in the Laredo immigration prison was conducted at the time and place cited, but the man's name may not have been Jos. All the refugees interviewed for this book knew that the author was writing a book and consented that their story be told. All people identified by full names have given permission for their use.

All articles cited from the Brownsville Herald, the Boston Globe , National Catholic Reporter, the Baltimore Sun, and Newsday are by the author unless noted otherwise.

The lawsuits Orantes-Hernandez v. Smith, Orantes-Hernandez v. Meese, and Orantes-Hernandez v. Thornburgh are one and the same case. The title of the suit was amended to substitute the name of the new defendant. This is also the case with American Baptist Churches v. Meese and American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh.

This book owes its existence to Barbara Ellington, my editor at Westview Press. Thanks also to her assistant, Patricia Heinicke, and to Jon Brooks, of Letra Libre.

Of the three thousand Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees I met, I am reasonably certain I saved one man's life. The Salvadoran government would have killed him if he were deported, and the only reason he wasn't deported is that I helped him get out of an immigration prison. This book is also for him, and for others who must be nameless.

Throughout the 1980s, a tiny number of prison workers worked much harder than I did and saved many more lives. Among them are Lisa Brodyaga, Patrick Hughes, Clare Cherkasky, Jonathan T. Jones, Jonathan Moore, Jack Elder, Peter Upton, Salvador Colon, Niels Frenzen, Meg Burkhardt, Thelma Garcia and her family, Jonathan Fried, Nancy Kelly, Tracy Jones, Danny Katz, Mark Schneider, Dora Jones, Karen Pettit, Sheila Neville, Peter Schey, Lucas Guttentag, Sam Williamson, Jeff Larsen, and the late James Cushman.

When California voters approved Proposition 187the "Save Our State" initiative that would deny public education and health care to undocumented immigrantsthey voted for a bill that even its authors acknowledged was unconstitutional. This state-rights initiative, approved by 59 percent of California voters in November 1994, came less than four years after the U.S. Department of Justice acknowledged in federal court that by denying fair trials to immigrants and by deporting refugees seeking political asylum to countries at war, it had violated its own laws and the Geneva Conventions more than 100,000 times.

The very name of the group that sponsored Proposition 187SOSis a measure of the hysteria attendant upon the issue of immigration to the United States today. After voters approved Proposition 187, federal courts blocked it immediately. The initiative will cost California millions of dollars to litigate, tens of millions of dollars to enforce, and billions in lost federal aid if the courts permit itwhich they will not. And even if it were constitutional, it is difficult to see how denying education to children or health care to the sick would benefit the state or the nation.

For more than a decade, the debate about immigration to the United States has been framed in terms that are dishonest and willfully amnesiac. By one measure, the anti-immigration forces have already won. No politician in either party today is prepared to say a good word about immigration. Yet the recent history of immigration to the United States, and the U.S. role in it, are a blank page in our national memory.

The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service was the foremost promoter of undocumented immigration during the 1980s. INS officials, directed by the U.S. attorney general, encouraged Nicaraguans to settle here, issued them work permits, and protected them from deportation, regardless of the weakness of their claims to political asylum.Alan Nelson and former INS Western District Commissioner Harold Ezellwere also chief enforcers of the immigration policies that violated U.S. laws. The U.S. Justice Department conceded this in the federal lawsuits American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh and Orantes-Hernandez v. Thornburgh. That these men led a voter initiative that is unconstitutional on its face, and that California's voters approved it overwhelmingly, is a sad measure of the misunderstanding of the nature of immigration, the misguided judgments about it, and the abuse and misconduct that have characterized U.S. immigration policy for more than a decade.

Issues related to human migration are virtually endless: economic growth and its limits, labor and workers' rights, language, culture, education, wars and civil wars, health, and the problems attendant upon each. But as immigration moves to the top of the national agenda, we should remember that most of us came here as immigrants. Blaming social and economic problems on immigrants may be convenient, but it doesn't explain anything, and it doesn't solve the problems.

Whether or not the impacts of illegal immigration are on balance negative, the fear of immigrants is useful to politicians. Proposition 187the centerpiece of Republican Governor Pete Wilson's successful reelection campaign in 1994would require public school teachers and health workers to denounce undocumented children and people seeking medical care to the INS, to be deported. Failure to report suspected undocumented people would be a violation of the law. Similar laws against the "failure to denounce" were the chief vehicle by which Joseph Stalin sent millions to the gulag. Yet liberal Democrats fear, rightly, that the remnants of their union constituency might resent lawmakers who are "soft on immigrants," whose cheap labor may hurt unions and depress wages. Thus the debate over immigration has been used to divide the body politic while it distorts national values. This noisy denunciation of immigration disguises a national ignorance of our calculated abuse of immigrants. "Fear, the worst of political counselors, has come to supersede thought."