Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Iric Nathanson

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.576.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015953415

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.792.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Over these past two years, I was able to draw on the help of many people as this book moved from the idea stage to the finished product.

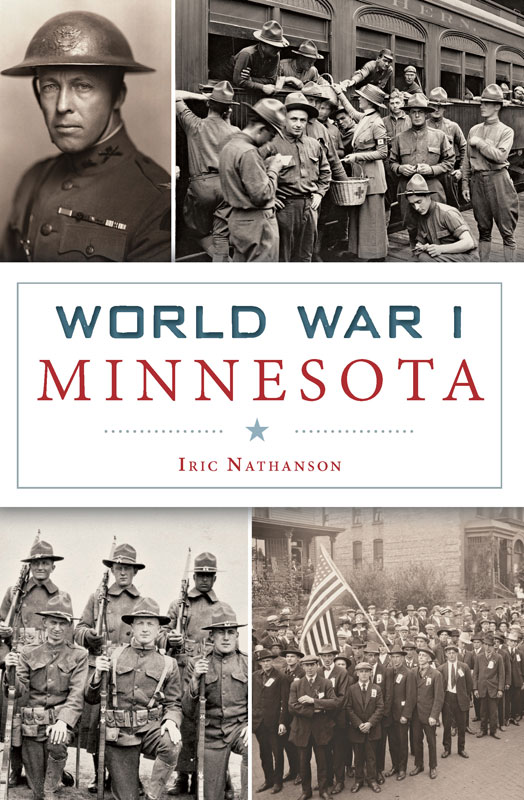

Staffs from archival agencies throughout Minnesota helped locate the images that made the story of World War I in Minnesota more vivid. They included Ted Hathaway and his team at the Hennepin County Library Special Collections, Susan Hoffman at the University of Minnesota Archives, Darla Gebhard from the Brown County Historical Society, Patricia Maus and Mags David from the Katherine A. Martin Archives at the University of Minnesota Duluth and Ellen Holt-Werle at the Macalester College Archives.

My friend Bill Skelton shared his expertise, gained over a long career as a professor of American history at the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point. My neighbor Carol Masters and my wife, Marlene, used their red pencilsbut did so gentlyto copy-edit my text.

And finally, acquisitions editor Greg Dumais at The History Press fielded my numerous early morning phone calls and kept me on track as this book came together.

My heartfelt thanks to all of you.

INTRODUCTION

Erst schaff dein Sach, Dann trink and lach. In English, it means First do your duty, then drink and laugh.

This cheerful German proverb and more than twenty others like it, ornamented in old Germanic script, decorate the walls of a unique space in the basement of Minnesotas state capitol, the rathskeller, a small caf open to the public when the Minnesota legislature is in session.

The German sayings first appeared in the capitol in 1905 to honor Minnesotas German Americans, then the states largest ethnic group. But twelve years later, on orders from Governor J.A.A. Burnquist, the innocent proverbs were painted over with layers of white paint to obscure their Germanic identity. The year was 1917. The United States had just entered World War I. With the temperance movement gaining momentum at home, German language signs promoting alcohol consumption had become offensive.

This country had entered the Great War, as it was known then, after the massive military struggle had been underway for three years. In 1914, when the first shots were fired on the European battlefields, the war seemed remote and of little relevance for many Minnesotans.

In the eastern United States, reports of so-called German atrocities generated widespread support for the Triple Entente powers of Britain, France and Russia. However, in the Midwest, according to historians Franklin Holbrook and Livia Appel, disapproval of Germany continued to be tempered for a long time by the prevailing sense of remoteness from the stage of conflict, lack of concern over the issues at stake, the pacific sentiments of the Scandinavian element and the openly expressed sympathy of the large body of German Americans.

With the U.S. declaration of war in April 1917, public opinion took a sharp turn in Minnesota. The Germansthe Huns as they were now calledhad become this countrys sworn enemies. In his order calling for the obliteration of the capitols harmless German slogans, Burnquists action was symptomatic of the nativist sentiment sweeping through a state just coming to terms with a war that would draw thousands of young Minnesotans to the European battlefields. Two decades later, even more young Minnesotans, many the sons of World War I veterans, would find themselves on the front lines of another worldwide military conflict.

On the surface, there were many similarities between life on the homefront during the two wartime eras. In World War I and again in World War II, Minnesotans demonstrated their patriotism and their support for the boys who were doing the fighting over there. Friends and neighbors back home were able to back the war effort by buying war bonds, volunteering with the Red Cross and conserving food and other scarce resources.

Despite these similarities, there were significant differences in Minnesotas political and social mood during the two wartime eras, separated by only twenty-two years. In 1939, the shock of Pearl Harbor unified the country and ended any real dissent about this countrys need to go to war in support of its European allies. Two decades earlier, the run-up to war had been a lot less sudden. True, Americans had been victims of German submarine attacks in the North Atlantic as far back as 1915, when the British ocean liner the Lusitania was sunk by German torpedoes. But the U.S. declaration of war in the spring of 1917 came at a time when a substantial segment of American public opinion was still in favor of neutralitynationally and here in Minnesota. This view was reflected in the votes of three Minnesota congressmen who opposed President Wilsons war resolution when the measure came before the U.S. House on April 6.

All three lawmakers represented congressional districts with sizable numbers of German Americans, many of whom were first generation immigrants with close ties to their homeland. While the overwhelming majority of these new Minnesotans professed their loyalty to the United States and their support for the war effort, some state opinion makers, who considered themselves 100 percent Americans, were convinced that German Americans were harboring a massive fifth column in Minnesota.

These suspicions helped create a dark undertone to the calls for state residents to demonstrate their patriotism. This undertone was reinforced by a powerful but short-lived state agency known as the Commission of Public Safety. The commission was organized in 1917 to mobilize support for the war and clamp down on dissent. In its disregard for civil liberties, the Minnesota commission represented a state precursor to the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities, established twenty years later, in 1938.

While anti-German sentiment in Minnesota during World War I never reached the level of enmity expressed toward Japanese Americans on the West Coast in the 1940s, it came close. In the largely German American community of New Ulm in southern Minnesota, two local officials were removed from office by the Public Safety Commission on grounds that their reservations about the military draft constituted disloyalty.

While the commission was contending with what it viewed as unpatriotic opinions expressed by some German Americans, it was facing other threats to the existing political and social order in Minnesota. The advent of war in 1917 coincided with the emergence of a major new political force that was sweeping into Minnesota from the west. Identified by the deceptively benign label as the Nonpartisan League, this left-leaning political movement had captured control of North Dakotas government in 1916.