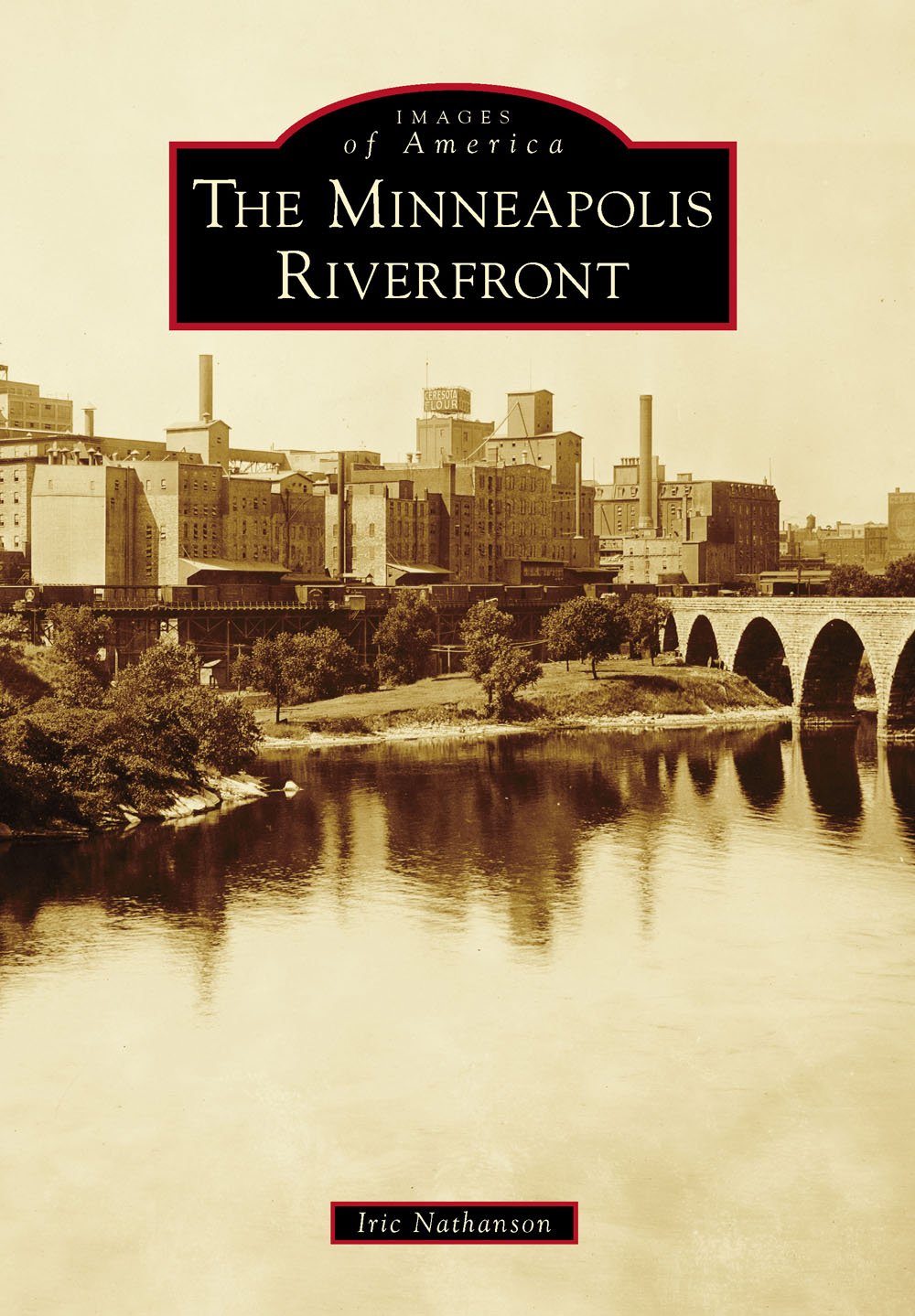

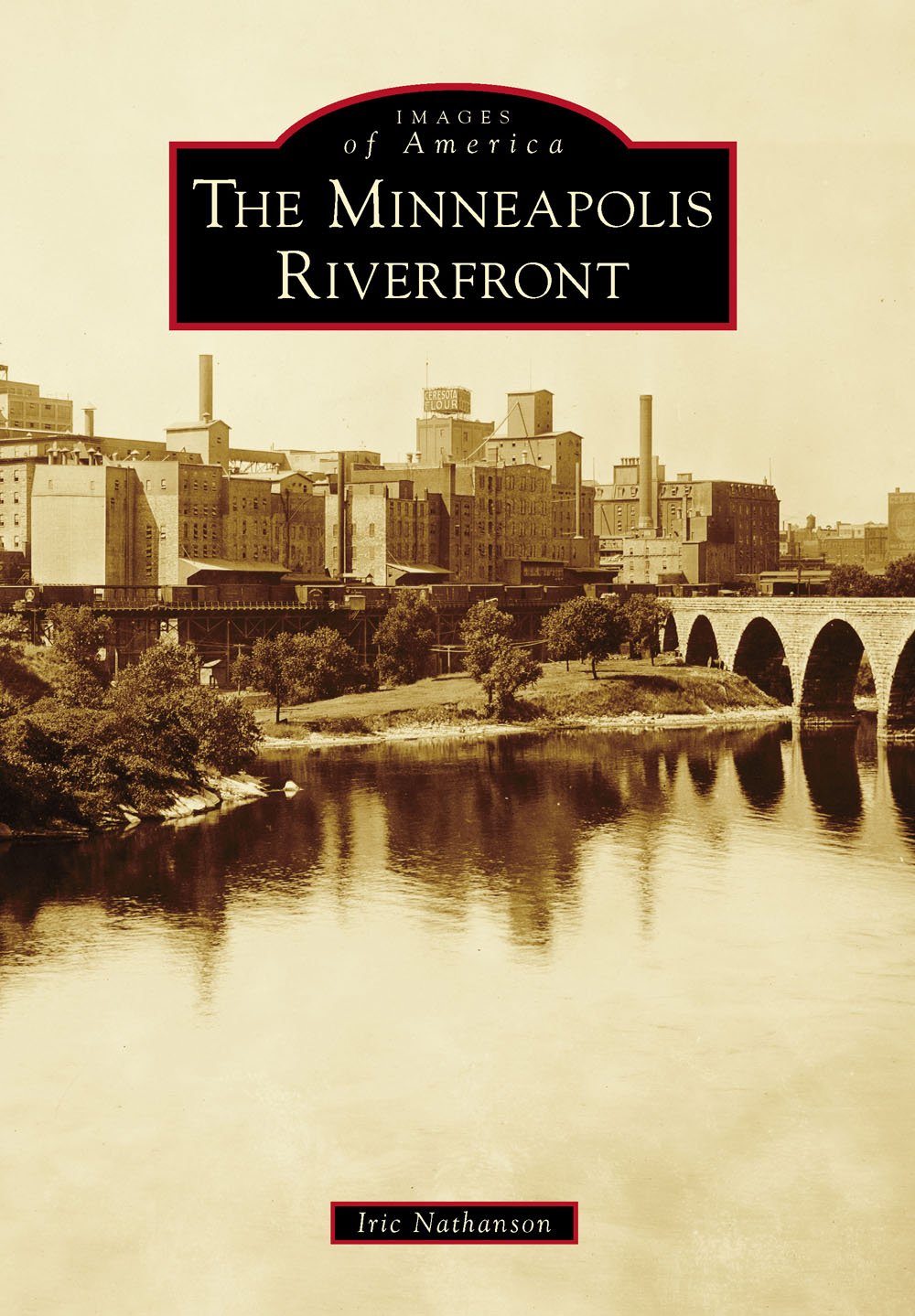

IMAGES

of America

THE MINNEAPOLIS

RIVERFRONT

ON THE COVER: The flour mills along the downtown riverfront propelled Minneapoliss economy during the citys first 50 years. The mills, in turn, were powered by the Falls of St. Anthony, the only true falls along entire the length of the Mississippi River. By the turn of the 20th century, these industrial concerns had made Minneapolis the milling capital of the world, a title the city would hold until the 1930s.

IMAGES

of America

THE MINNEAPOLIS

RIVERFRONT

Iric Nathanson

Copyright 2014 by Iric Nathanson

ISBN 978-1-4671-1276-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439648698

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941398

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Marlene Nathanson

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have happened without the help of the people who pointed me in the right direction as I moved ahead with this project for Arcadia Publishing.

My friend and former neighbor Mike Till introduced me to Arcadia and the helpful people there who oversee its Images of America series.

Staff members at the local history depositories helped with the daunting task of assembling more than 180 images for this book. They included Ted Hathaway, Bailey Siers, and Gail Wolfson with Hennepin County Library Special Collections; Eric Mortenson and Jennifer Huebscher with the Minnesota Historical Society; and Susan Larson-Fleming with the Hennepin County History Museum.

More photographs and useful information came from John Anfinson with the National Park Service and Dave Sheppard with the Minneapolis Rowing Club. Carol Hanson was able to share photographs and memories of her mother, Reiko Weston, who helped launch Minneapoliss riverfront revival.

Dave Stevens with the Mill City Museum and Ann Calvert with Minneapolis Community Planning and Economic Development took time out from their busy schedules to review and comment on sections of my text.

My editor at Arcadia, Maggie Bullwinkel, kept me on task, and always did so in a pleasant and helpful way.

And finally, my wife, Marlene, cheered me along during those long hours that I spent hunched over the computer.

INTRODUCTION

With the Mississippi River flowing through its urban center, Minneapolis forged close connections to its riverfront during its early years.

The citys origins extend back to the 1850s, when it was a tiny frontier settlement hugging the banks of the river at the only true falls along the Mississippi Rivers entire length. The power generated by this cascading flow would serve as the citys economic engine during its first half century.

Two centuries earlier, Franciscan priest Fr. Louis Hennepin came across the falls during his exploration of the Upper Mississippi and named the raging cataract for his patron saint, St. Anthony of Padua. The ecclesiastical designation would continue to identify the falls up through modern times, but Native Americans who lived nearby called it by different names: for the Ojibway people, it was Kakabikah (severed rock), while the Dakota people knew it as Minirara (curling water) or Owahmenah (falling water).

The area around St. Anthony Falls remained the preserve of the Ojibway and the Dakota until the 1820s, when a US military outpost was built on a bluff seven miles away, overlooking the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. Originally named Fort St. Anthony, the post was later renamed for one of its early commandants, Josiah Snelling. In order to supply flour and lumber for the frontier post, soldiers from Fort Snelling made their way down to the falls and built the first mills to harness the power of what was then a raging wilderness cataract.

Up through 1837, land on the west bank of the falls was part of the Fort Snelling military reservation, while land on the east bank remained under the control of the local Indian tribes. That year, a treaty with federal government forced the tribes to give up their rights to the east bank, and a land rush was soon underway.

A young civilian named Franklin Steele, who worked at the fort, received advance notice that the treaty had been ratified. Steele staked his claim on the east bank of the river overlooking the falls. He would later establish the town of St. Anthony at that site. His town encompassed a small island named for early French explorer Joseph Nicollet.

In 1855, a 28-year-old New Hampshire native named John S. Pillsbury arrived in the tiny frontier settlement. Pillsbury opened a hardware store, prospered, and soon became one of St. Anthonys leading citizens. Later, he was joined by his nephew Charles and other family members. In 1865, Charles and John purchased an interest in a small flour mill, located on the towns east bank. Renamed the Pillsbury Mill, the fledging business would later emerge as one of Minnesotas industrial giants.

Across the river, the west bank, part of the Fort Snelling reservation, was off-limits to settlementat least officiallythrough the 1840s and into the early 1850s. But the off-limits designation did not deter a ragtag collection of squatters who moved on to the land along the river and built crude frame homes there.

In 1852, an act of Congress severed 26,000 acres from the forts jurisdiction and opened it to private development. Once again, a riverfront land rush occurred, and a new community soon took shape on the Mississippis west bank. Early settlers realized that they needed a name for their small settlement, but they opted not to identify themselves with Catholic saints as their counterparts in St. Anthony and down the river, at St. Paul, had done. Instead, they decided to create a new name that linked the Dakota term minnehaha, which stood for laughing water, with the Greek word polis, which stood for city. The amalgam became Minnehapolis. Later, the h was dropped, and the new settlement became known as Minneapolis.

Soon, a string of small mills began to appear along the west-bank riverfront. In 1855, the new community of Minneapolis was linked to its older counterpart on the east bank, St. Anthony, when a suspension bridge across the Mississippi River joined the two settlements. By now, business leaders on both sides of the Mississippi River had organized themselves to manage the waterpower generated by St. Anthony Falls. On the west side, the group included Dorilius Morrison, who would become one Minneapoliss richest men and the citys first mayor. Morrison was soon joined by a Wisconsin businessman, Cadwallader Washburn, who later built a mill that bore his name.

On the east bank, local business leaders created the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company to develop their side of the fall. In 1869, east-siders faced a major setback when a tunnel they were building under the river collapsed. Across the river, Morrison, Washburn, and their Minneapolis Mill Company were more successful with their project, which diverted the flow of the Mississippi through a tunnel and down over a series of turbines that powered each of the mills.

In 1878, Washburn faced his own disaster when his A Mill exploded, killing 14 of his workers. Washburn moved quickly to rebuild. When his new mill open in 1880, it was the newest, most up-to-date facility of its kind anywhere in the country.

Next page