IMAGES

of Modern America

DOWNTOWN

ST.PAUL

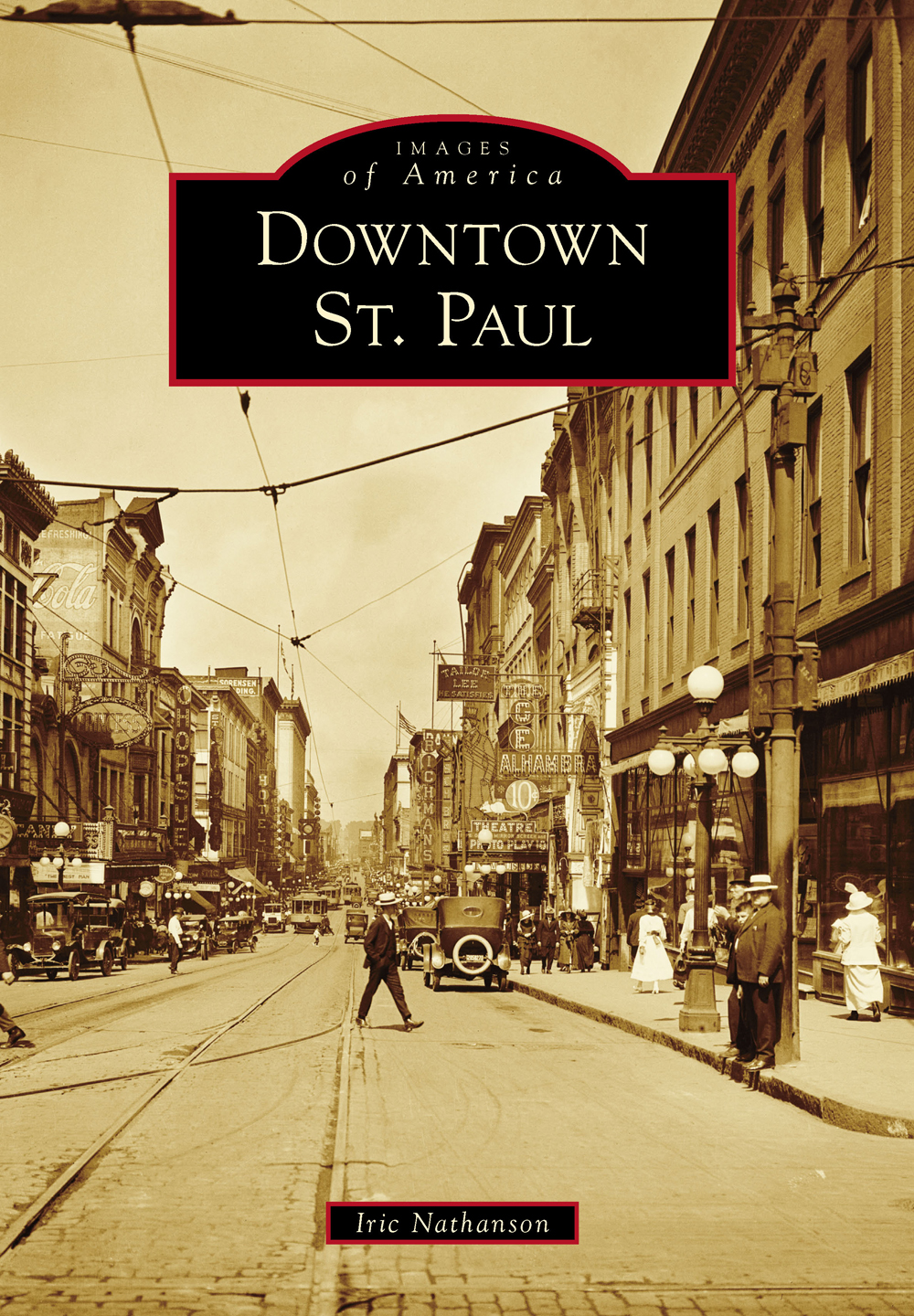

ON THE COVER: St. Pauls Seventh Street was a busy place on this summer day in 1922. (Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.)

IMAGES

of America

DOWNTOWN

ST.PAUL

Iric Nathanson

Copyright 2019 by Iric Nathanson

ISBN 978-1-4671-0246-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439666319

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941135

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Marlene.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During this past year, I was able to draw on the expertise of the many people who helped make this book a reality. Three longtime observers of the St. Paul scene took the time to review my early drafts. David Beal, John Lindley, and Steve Trimble caught some glaring errors and offered many useful suggestions. Ted Hathaway and his staff at Hennepin County Public Library Special Collections located a number of the archival images included in this book. Rich Arpi from the Ramsey County Historical Society and Eric Mortenson with the Minnesota Historical Society also helped me access the extensive photographic archives maintained by their organizations. Weming Lu and Mary Arvanitis provided photographs from their personal collections. Finally, Angel Hisnanick, my editor at Arcadia Publishing, kept me on track as this project moved from the idea stage to the final product. All images are courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society unless noted.

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1840s, a tiny frontier settlement took shape along the upper reaches of the Mississippi River. The settlement consisted of a few ramshackle cabins overlooking the riverfront on a site that would later become downtown St. Paul.

In later years, St. Paul would be known as the Saintly City. But the tiny settlement had a much less lofty name in the beginning. It was called Pigs Eye after a disreputable liquor dealer with a misshapen eye known as Pierre Pigs Eye Parrant,- who ran a tavern there. Luckily for future generations, the original name was short-lived. When a French priest, Fr. Lucien Galtier, arrived in 1840 to bring religion to the tiny settlement, he renamed the place for a Christian saint. The name Saint Paul applied to a town or city seemed appropriate, Father Galtier later recalled. The monosyllable is short, sounds well and is understood by all denominations of Christians. Later, the Catholic Church, led by Archbishop John Ireland, would play an important role in the social life of St. Paul.

When Father Galtier came to St. Paul, the frontier was moving west into what later became the state of Minnesota. Land had just been opened to white settlement as a result of treaties with the local Indian tribes. With its strategic location at the head of navigation on the Mississippi River, St. Paul soon become the commercial center of a Midwestern region filling in with farms and towns.

In 1849, St. Paul took on a political role when it became the capital of the newly created Minnesota Territory. That led to a real estate boom. When it was designated the territorial capital, St. Pauls population was just under 1,000. Nine years later, when Minnesota was admitted to the union as the 32nd state, that number had ballooned to just under 10,000.

During those boom years, young men on the move were finding their way to St. Paul from all over North America. One of those was an 18-year-old Canadian named James J. Hill. Soon after arriving in town, Hill found a job as a bookkeeper for a steamboat company. Within a few years, he was on his way to becoming St. Pauls wealthiest and most prominent business leader. By the 1890s, as the head of the transcontinental Northern Pacific Railroad, Hills prominence and wealth had earned him a place on the national stage.

Hill made St. Paul his base of operations, but his reach kept extending farther west as his railroad empire expanded. In Minneapolis, Hill built the landmark Stone Arch Bridge to bring his trains into that citys downtown. The Stone Arch overlooked St. Anthony Falls, the only true falls along with entire length of the Mississippi. With the waterpower it generated, the falls gave Minneapolis, the younger of the Twin Cities, a resource that its older twin, St. Paul, lacked.

St. Anthony Falls powered a series of flourmills that would soon make Minneapolis the flour milling capital of the world. By the turn of the last century, with Minneapolis surpassing St. Paul in terms of population and economic growth, St. Paul civic leaders came to realize that their city would not become the dominant economic center of the Upper Midwest as they had hoped it might one day. Still, they had a thriving downtown serving a community whose population would later exceed 300,000.

During the first half of the 20th century, St. Paul residents flocked to downtown using the network of streetcar lines that converged there. Initially, downtowns retail district was centered on Third Street, at the edge of the bluff overlooking the riverfront. However, by the end of the 19th century, the retail district had moved north and west, away from the riverfront, leaving Third Street to decline into a shabby skid row. It was later replaced by a landscaped roadway known as Kellogg Boulevard.

Beyond Third Street, the blocks between Fifth and Seventh Streets filled in with elegant department stores and elaborate movie palaces. At one point, Seventh Street was home to several dozen movie theaters, making it St. Pauls Great White Way.

Downtown St. Paul survived the turmoil of the Great Depression and World War II but succumbed to the wave of postwar suburbanization that threatened aging urban centers all across the country. One by one, St. Pauls department stores and movie theaters closed as shoppers abandoned downtown for the new suburban malls.

Downtown was able to offset its decline, at least in part, because of its location as the site of Minnesotas state capitol. State governments expanded role during the postWorld War II decades helped fill downtown office buildings with thousands of state employees. But those workers departed at the end of the working day, leaving downtown streets empty and desolate.

During these postwar years, downtown was reshaped by urban renewal and highway projects that cleared away much of its stock of 19th-century commercial buildings. Luckily, a number of downtowns most architecturally significant structures were preserved, even while many of the early commercial blocks were leveled. Starting in the 1970s, the seeds of downtowns revival were planted when local civic leaders came to realize that many of the commercial districts early buildings contained great hidden value behind their shabby facades. The adaptive reuse of St. Pauls turn-of-the-century federal building was the first in a series of important historic preservation efforts that helped rebuild downtown.

During the early years of the 21st century, St. Pauls central business district took advantage of its rich history to become an important cultural and entertainment center. By rediscovering its roots, downtown St. Paul has created a bright future for itself during the new millennium.

One

EARLY YEARS

When the early settlers arrived at a wooded site along the Upper Mississippi, they discovered two clefts in the river bluffs about a mile apart. These breaks in the bluffs enabled the settlers to drive their wagons down to the river to meet the boats traveling up and down the Mississippi. The two riverfront sites became St. Pauls Upper and Lower Landings, which served as anchors for the frontier settlement that would later become modern-day downtown St. Paul.

Next page