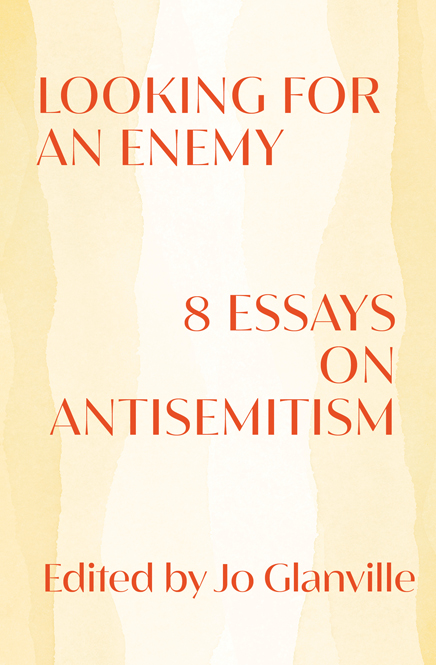

Jo Glanville - Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism

Here you can read online Jo Glanville - Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Norton, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism

- Author:

- Publisher:Norton

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

LOOKING FOR

AN ENEMY

8 ESSAYS ON

ANTISEMITISM

Edited by JO GLANVILLE

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

ANTISEMITISM NEVER GOES out of fashion. It adapts endlessly to the anxieties of the age. Pandemic? Jews are behind it. Immigration? Jews are orchestrating it. Terrorist atrocity? A Zionist plot. Over the past few years these Jewish conspiracy theories have entered the mainstream, from President Trumps rumour-mongering about Jewish investor and philanthropist George Soross supposed malign influence to Labour Party members in the UK accusing Jews of various Zionist plots. In Europe and America, antisemitic incidents have reached an historic high. In 2018, the German government appointed its first antisemitism commissioner; in 2020, the United Nations announced a special envoy to combat antisemitism. The evidence adds up to a startling trend: more than 75 years after the Holocaust, despite education programmes and international memorialisation of the genocide, antisemitism is circulating across the political spectrum.

For this anthology, I asked writers in Europe, Israel and America to contribute essays that would offer a greater understanding of antisemitisms resurgence, reporting from their home fronts as well as taking on the universal themes. Some essays include illuminating and moving memoir, others political or historical commentary. They are a reminder that the far right remains a bigger threat to Jews than the left, that the roots of contemporary antisemitism run deep and long pre-date the Holocaust and the foundation of Israel, and that each country has its own complex relationship with Jews, shaping an often inadequate response to antisemitism. All bring insight into antisemitisms enduring appeal and the factors that enable it to survive. In the title essay, Daniel Trilling shows how the Jewish conspiracy theory is the glue that binds disparate far right groups together. Modern antisemitism is not, he argues, a continuation of an ancient prejudice, but the search for an enemy to blame in turbulent times. In France, as Natasha Lehrer reveals, Jews paradoxically find themselves sidelined from the current debate on racism, even though they are still frequent targets of antisemitism. In Poland, where discussion of Polish participation in the Holocaust has been outlawed, Mikoaj Grynberg describes a childhood overshadowed by the impact of antisemitism on his family. As an adult, he is encountering the same open racism that his grandparents faced.

All racism shares the idea that the minority group will inflict some kind of harm on the majority, but antisemitism is underpinned by a belief that Jews are secretly in control and intend to use their power to ill effect, whether to control the media or global finance. The idea that Jews are plotting harm has been repeated so often that it has come to be treated as fact whether the respected actor Maxine Peake stating in an interview in 2020 that Israeli secret services trained the US police in the tactics that killed African-American George Floyd (for which she apologised) or the much repeated claim regarding the Rothschild familys global control. In her book Denying the Holocaust (which famously resulted in Holocaust denier David Irvings failed libel suit), Deborah Lipstadt showed how the transformation of Jews from victims into victimisers is central to Holocaust denial: deniers accuse Jews of creating a myth of genocide in order to extort reparations from Germany and fund Israel, as part of a Zionist masterplan. It is a chilling inversion of victimhood that characterises most antisemitism.

This is a narrative that has cemented prejudice and reaffirms a deeply entrenched cultural belief that goes back to the origins of Christianity. The vilification of Jews as sinful betrayers, killers of Christ, is so fundamentally rooted in Christian culture that it may explain why, even in a secular society, there is still a sense that its actually reasonable not to like Jews. It has been culturally acceptable to dislike Jews for far longer than it has been taboo to discriminate against them. In his revelatory book Anti-Judaism, the historian David Nirenberg has shown how hostility towards Judaism, and Jews, was transmitted from early Christianity into western philosophy it is embedded in the very DNA of western culture.

In the UK, the re-emergence of antisemitism is a shock, partly because we still think of ourselves as the good guys: we defeated Hitler, were on the side of the Jews. However, as the historian Tony Kushner has shown, antisemitism continued in Britain throughout the war, and afterwards. The Jewish problem is created by the Jews themselves, Kushner quotes from the July 1946 Mass Observation social survey, which captured the views of members of the public. Nobody would interfere with Jews, not even Nazis, if they had not made themselves so conspicuous and hateful. The best solution would be for the Jews to pipe down.

So antisemitism has never gone away, not even in the face of the genocide of European Jews. Whats new is an unashamed, though sometimes veiled, antisemitism in political discourse, alongside the rise in antisemitic hate crimes. Some commentators have put this visibility down to the rise of populist politics, on left and right, which has long been a feature of modern antisemitism, playing on the notion of an exploitative elite and echoing conspiracy theories. Others have observed the transition of far-right views into the mainstream, as Daniel Trilling investigates in his essay. Nor can antisemitism be separated from a rising xenophobia that targets Muslims and migrants, and which has also been encouraged by politicians, including President Trump and various European leaders. Some observers have claimed credibly that anti-migrant rhetoric influenced Robert Bowers assault on worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh on 27 October 2018, the worst attack on Jews in US history. Bowers accused Jews of bringing evil Muslims into the US.

Although Muslims and Jews clearly share a common enemy (and have historically been cast as co-conspirators), extremist European Muslims have emerged as a more recent threat to Jews. In an EU survey in 2018, respondents were asked to describe the perpetrator of the most serious incident of antisemitic harassment experienced in the past five years. Respondents in 30 per cent of cases identified the perpetrator as someone with Muslim extremist views, while 13 per cent identified the perpetrator as someone with a right-wing political view. Natasha Lehrer details some of the most shocking incidents in France over the past decade in her essay, including the murder of Jewish hostages at the Hypercacher kosher supermarket in 2015. However, novelist Olga Grjasnowa challenges the current narrative in Germany that singles out Muslims as the greatest threat to German Jews, when in fact the majority of antisemitic crimes in 2019 were committed by the far right, a trend that continued in 2020.

Despite the clear rise in antisemitism, there is a perplexing failure to recognise it. Its quite possible to be an avowed anti-racist and still be an antisemite, as members of the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn demonstrated. How is that feasible? European and American Jews do not fit with the model of victims of racism: they are perceived as privileged and as white, and therefore cannot be oppressed. As Philip Spencer observes in his essay on antisemitism and the left, they are seen as part of the global power structure. This resistance to viewing Jews as casualties of racism is part of the long history of seeing them as oppressors themselves, the victims as victimisers. The response of Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters in the UK to the Equality and Human Rights Commissions damning report on antisemitism in the Labour Party in October 2020 replayed this distorted narrative: the scale of the problem was dramatically overstated for political reasons, Corbyn claimed, by the media and by opponents. After his suspension from the Labour Party, it was Corbyn who was identified as the victim by his supporters, while Jews were apparently exaggerating their victimhood or even (once again) behind a conspiracy. It is deeply disturbing that Corbyn and his supporters continued to cast doubt on the spread of antisemitism in the party after a statutory public body identified a culture that not only failed to do enough to prevent racism against Jews but even accepted it.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism»

Look at similar books to Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Looking for an Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.