Simon Prince - Belfast and Derry in Revolt

Here you can read online Simon Prince - Belfast and Derry in Revolt full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Irish Academic, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Belfast and Derry in Revolt

- Author:

- Publisher:Irish Academic

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Belfast and Derry in Revolt: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Belfast and Derry in Revolt" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Belfast and Derry in Revolt — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Belfast and Derry in Revolt" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

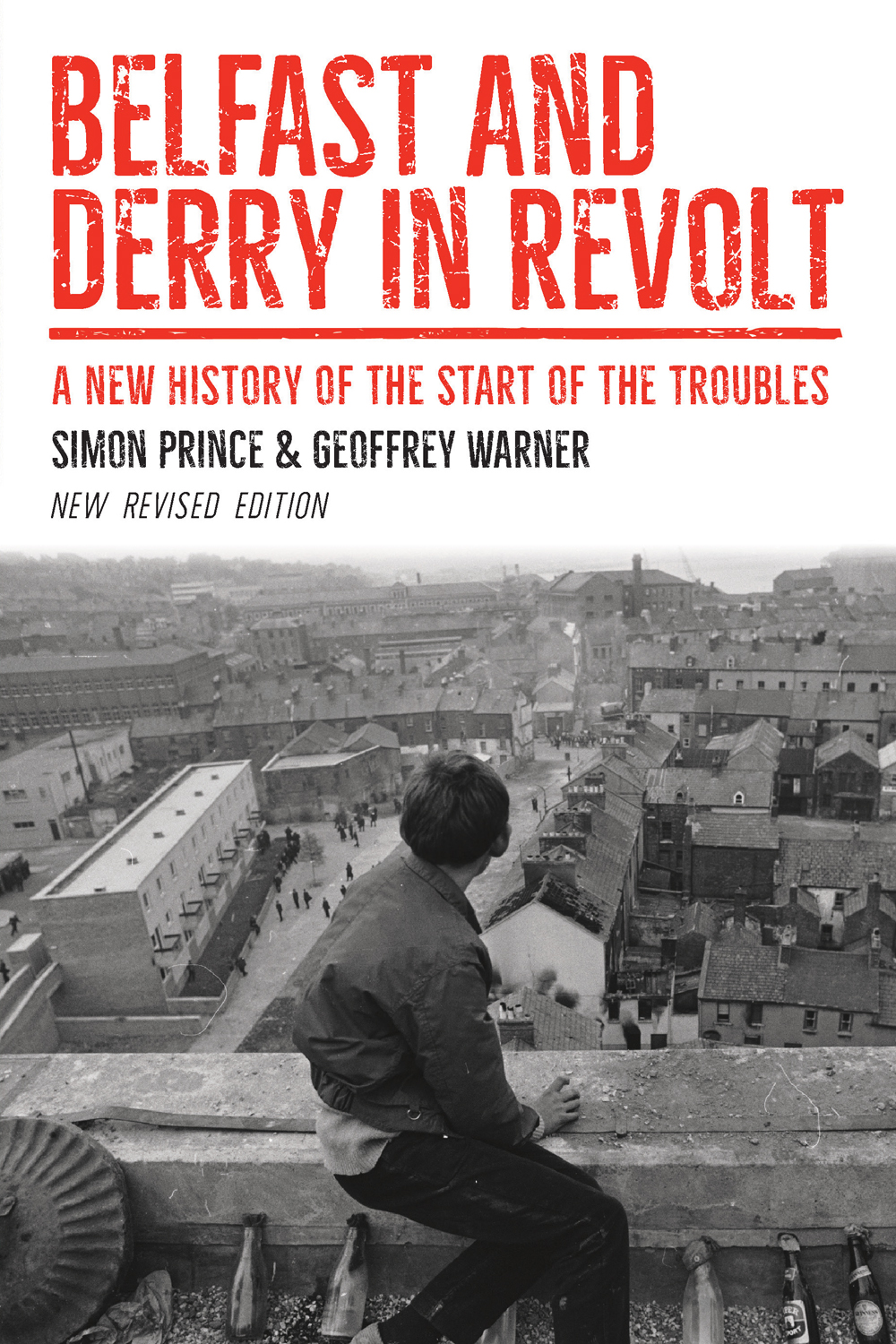

BELFAST AND DERRY

IN REVOLT

Simon Prince is Senior Lecturer in Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church Universitys School of Humanities. His publications include Northern Irelands 68: Civil Rights, Global Revolt and the Origins of the Troubles (IAP, 2007; New Edition, 2018).

Professor Geoffrey Warner is a Supernumerary Fellow in Modern History at Brasenose College Oxford. He is the author of many books and has published widely in the field of Northern Irelands history.

BELFAST AND DERRY

IN REVOLT

A New History of the Start

of the Troubles

NEW REVISED EDITION

Simon Prince

&

Geoffrey Warner

First published in 2012; new revised edition published in 2019 by

Irish Academic Press

10 Georges Street

Newbridge

Co. Kildare

Ireland

www.iap.ie

Simon Prince & Geoffrey Warner, 2019

9781788550932 (Paper)

9781788550949 (Kindle)

9781788550956 (Epub)

9781788550963 (PDF)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved alone, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Typeset in Classical Garamond BT 11/15 pt

Cover: The Troubles: Derry riots, Derry, 1969.

(Gilles Caron copyright: Fondation Gilles Caron/Clermes)

Contents

Preface

O nce upon a time was how the Derry radical Eamonn McCann began an August 1969 pamphlet that told his story of the civil rights movement.

Activists have worked hard to construct and sustain narratives about how a civil war began in a devolved region of the United Kingdom. Indeed, as the fiftieth anniversaries roll round, the tales are getting told again. Belfast and Derry in Revolt: A New History of the Start of the Troubles challenges those narratives. The book serves four closely related purposes. First, it rejects the story of a loyalist backlash to the civil rights movement and the republican campaign of violence, showing instead that they were the first to march and to shoot. Second, it questions the twin assumptions that the civil rights movement was a unitary actor and that non-violent direct action was a peaceful form of protest. Third, it refutes claims that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) acted defensively and that the Belfast brigade failed to protect their neighbourhoods. And finally, it casts doubt on the idea that the start of the Troubles had a single cause, shifting attention over to how violence was produced by a set of developments that, in turn, triggered further developments. The outbreak of civil war in Belfast and Derry cannot be explained in terms of a unique underlying cause.

Before the IRA fired a gun and before civil rights marchers took a step, a small number of loyalists were on the streets fighting phantoms. They believed that rebels were on the brink of attacking Northern Ireland; they believed the people needed to take the actions that their representative government was failing to take. But republicans were not ready for another armed campaign and Stormont had taken thorough precautions ahead of the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising. When a Protestant widow from the Shankill was murdered in the spring of 1966, the perpetrators were from the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), not the IRA. Contrary to what the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) had concluded, the incendiary preacher Ian Paisley never directly assisted loyalist paramilitaries. He did, however, inspire many of them to get involved in militant politics. The combination of agitation and assassination weakened Stormont and strengthened those republicans and leftists who were seeking revolutionary change. In other words, it achieved the opposite of what Paisley and the UVF claimed they had set out to do.

The second purpose of the book is to better understand how the civil rights movement could be so successful, so quickly, and yet fall apart so soon afterwards. The people who met in Derry on 5 October 1968 to march for civil rights represented, according to the commission of inquiry, most of the elements in opposition to the Northern Ireland Government.

The fragmentation and competition within the civil rights movement gave it dynamism. A tiny band of leftists, who had embraced direct action, pushed more moderate figures into taking up non-violent strategies. As McCann recalled in February 1969, he had been in the street when it was a fairly lonely place to be [and when] respectable gentlemen ... were noticeable by their absence. Fragmentation and competition, however, meant that the civil rights movement was divided over how to respond to the governments reform package. While the moderates chose to pause their protests, the radicals decided to maintain the pressure. The disorder therefore did not end. For those individuals and organizations willing to use violence in pursuit of their goals, opportunities now began to open.

The third aim of Belfast and Derry in Revolt is to challenge the narrative that presents IRA violence as defensive in nature. Republican militants were not backed into taking a stand against a police force that had united with loyalist mobs. Our case is driven home by an analysis of the August 1969 violence in north and west Belfast, during which eight people died and many more were injured. The IRA was, in fact, behind the first incidents on 13 August 1969. Following the Belfast commanders order to get the people on to the streets, IRA volunteers led a march from Divis Flats to the local police stations, one of which had petrol bombs thrown at it. The republicans turned the tide.

It is a remarkable fact, to use the tribunal of inquirys phrase, that other parts of Belfast remained quiet during those hot summer nights. Disturbances were sparked on the Falls Road and in Ardoyne, where the IRA was active; similarly, they were instigated around the Shankill Road, where the Shankill Defence Association (SDA) was on the streets and the UVF was lurking in the shadows. In each case, political action by militant entrepreneurs set the pattern of events. Organizations mobilized individuals, provided them with the chance to participate, and co-ordinated their actions. Indeed, organizations paramilitaries but also political parties, state agencies, Churches, trade unions, and interest groups were the principal actors in the drama.

This point can be illustrated further by examining the Shankill riots of 11/12 October 1969. In Belfast and Derry in Revolt , we rather overlooked the significance of this event. New archival material, however, shows that the clashes were not an improvised response to the release of the Hunt Report into policing that day. Over a week before the riots, reports came in to the intelligence services that the SDA and UVF were planning multiple demonstrations to overstretch the RUC and drag in the army. Finally, on 10 October, Special Branch sources confirmed that the loyalist plan to confront the security forces was about to be put into action. Beginning with a lunchtime sit-down protest, the sequence of demonstrations stuck to the timetable acquired by Special Branch. As day turned to night, the RUC struggled to shield Unity Flats seen by loyalists as an IRA citadel from a crowd of around two thousand men. With the pubs letting out Saturday-night drinkers, the police chose to call in the army. According to the Irish News , the soldiers were greeted with shouts of Englishmen go home.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Belfast and Derry in Revolt»

Look at similar books to Belfast and Derry in Revolt. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Belfast and Derry in Revolt and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.