Table of Contents

Guide

F irst, all praise is due Diane Wachtell and The New Press. The basic idea for this book came out of a conversation with Diane in 2015. We are grateful for the existence of an editor with an interest in criminal justice and a publisher with a commitment to books about public policy.

Second, this book would not be possible were it not for the Center for Court Innovation, the agency where we both work. The Center provided us with time and space to write. More important, it provided us with inspiration. This book chronicles many of the reform efforts and ideas that the Center for Court Innovation has championed over the years. We hope we have done them justice in these pages.

We thank the people who helped give birth to the Center for Court Innovation in the early 1990s, among them John Feinblatt (the Centers founding director), Mary McCormick, Eric Lee, Michele Sviridoff, the late Judith S. Kaye, and Jonathan Lippman. We also thank the policymakers and funders who support the Center on an ongoing basis. This includes the New York court system (Janet DiFiore, Larry Marks, and Ron Younkins), the New York City Mayors Office (Liz Glazer), the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (Laurie Garduque, Soledad McGrath, Patrick Griffin, and Maurice Classen), among others.

Dozens of our friends and colleagues at the Center for Court Innovation contributed to this book, offering advice and feedback and encouragement. We thank Adam Mansky, Liberty Aldrich, Michael Rempel, Sarah Fritsche, Julius Lang, Rob Wolf, Courtney Bryan, Katie Crank, Erika Sasson, Kate Barrow, Yolaine Menyard, and Jennifer Tallon for their help.

More specifically, we thank Samiha Amin Meah for her help with infographics. We thank Serin Choi, Phil Bowen, and Matthew Watkins for their comments on the introduction. We thank Raphael Pope-Sussman for his contributions to chapter 1. We thank James Brodick, Erica Tapia, Deron Johnston, Amy Ellenbogen, Kenton Kirby, and Ife Charles for helping us with chapter 2. We thank Jethro Antoine, Kelly Mulligan-Brown, Emily LaGratta, Victoria Pratt, Alex Calabrese, and Amanda Berman for their assistance with chapter 3. We thank Aisha Greene and Lenore Lebron for their help with chapter 5. We thank Aaron Arnold and Valerie Raine for their comments on chapter 6. Rebecca Thomforde-Hauser helped us with chapter 7. And we could not have pushed this book over the finish line without the help of Isabella Banks, Rebecca Thomson, Tamar Hoffman, Patrick McMenamin, and Lauren Speigel, who provided research support and spent hours cleaning up the manuscript.

Beyond the Center for Court Innovation, our thanks to everyone who agreed to be interviewed for this book. Some of these people are our friends. Some are people we met for the first time through this process. What they all have in common is a passion for improving the criminal justice system. We thank them for sharing their time and ideas with us.

Finally, we offer the following personal thanks.

Greg: To Carolyn, Hannah, and Milly Bermanit is a blessing to live with three great writers and funny people. Thanks for bringing mirth and kindness and perspective to my life. To Michele and Allan Bermanthanks for believing in my potential. And to M.J.thanks for modeling perseverance and grace in the face of adversity.

Julian: To Erica Adlerfor endless love and unflinching support. To Amelia and August Auggie Adlerfor so much inspiration, so much warmth, so much tomfoolery. And to Helen and Elliot Adlerfor keeping the faith.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Greg Berman is the director of the Center for Court Innovation. He has accepted numerous awards on behalf of the Center, including the Peter F. Drucker Prize for Nonprofit Innovation. He is the author/co-author of Trial & Error in Criminal Justice Reform, Reducing Crime, Reducing Incarceration, and Good Courts: The Case for Problem-Solving Justice.

Julian Adler is the director of policy and research at the Center for Court Innovation. He was previously the director of the Red Hook Community Justice Center and the lead planner of Brooklyn Justice Initiatives. He was also part of a small planning team that launched Newark Community Solutions.

ALSO BY GREG BERMAN

Good Courts (with John Feinblatt)

Reducing Crime, Reducing Incarceration

Trial & Error in Criminal Justice Reform (with Aubrey Fox)

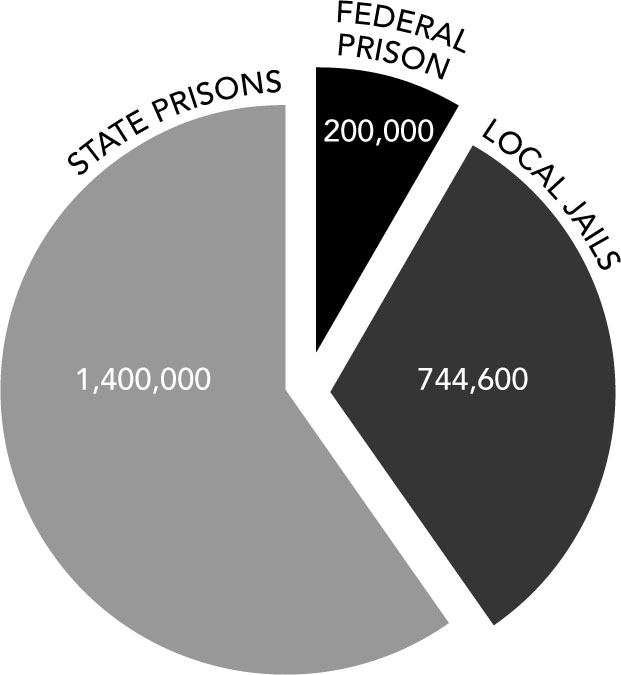

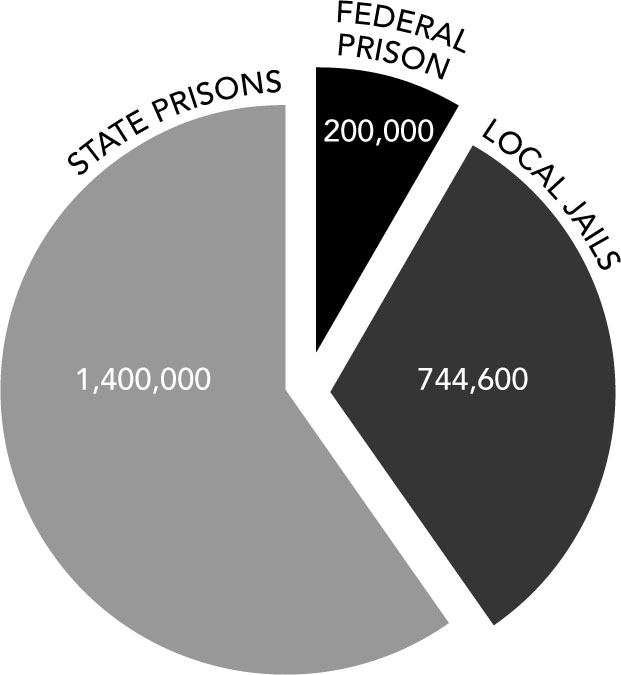

2.3 million Americans are behind bars: approximately

1.4 million people are serving time in state prisons,

744,600 in local jails, and 200,000 in federal prison

I n his 2015 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama issued a bipartisan call for criminal justice reform: Surely we can agree its a good thing that for the first time in 40 years, the crime rate and the incarceration rate have come down together, and use that as a starting point for Democrats and Republicans, community leaders and law enforcement, to reform Americas criminal justice system so that it protects and serves us all. As President Obama highlighted, in recent years, the rate of incarceration has actually begun to decline in the United States. Thats good news, of course. But, according to criminal justice expert Michael Jacobson, this doesnt mean that we are on a path to ending mass incarceration.

Jacobson knows the challenges of incarceration reduction firsthandback in the 1990s, he served as New York Citys corrections commissioner, overseeing the citys jails at a time when there were twenty thousand inmates on Rikers Island on any given day. Today he analyzes jail populations as part of his work at the Institute for State and Local Governance at the City University of New York.

According to Jacobson, turning back the clock to the 1970s, when America incarcerated its citizens at a rate that was similar to the rest of the worlds developed countries, would take about one hundred years if we continue on our current trajectory. In his accounting, even the goal of cutting the incarcerated population by 50 percentthe stated target of the reform coalition #cut50wouldnt get it done. That does not end mass incarceration, argues Jacobson. Our rates would still far exceed all other comparisons.

The problem? Violent offenders. Theyre a perilous third rail for policymakers, especially elected officials who remember how the specter of Willie Horton helped to derail Michael Dukakiss presidential ambitions.

Many reformers prefer to obscure this reality, focusing on miscarriages of justice or minor drug offenders who are languishing behind bars. But if were serious about changing course, it will require reckoning with how we understand the mission of our justice system and how we view our fellow citizens who have committed acts of violence at one point or another. We are such an outlier in how we treat those folks, Jacobson observes. We have no discussion of human dignity or redemption.

Ending the overuse of incarceration in the United States is possible. But it is not possible unless we take a close and honest look at who is currently behind bars.

THIS IS NOT ABOUT WHAT THE PRESIDENT DOES

The United States locks up more of its citizens than any other country on earth. There are more people behind bars in the United States than the incarcerated populations in India and China combined. On a per capita basis, this amounts to incarcerating eight times as many people as Germany, five times as many as Australia, and more than twice as many as Iran.

The incarceration rate in the United States is around 700 inmates per 100,000 peopleabout one out of every 140 people. But an even starker picture emerges if you consider the incarceration rate for adults. Nationally, one in 100 Americans eighteen years and older is behind bars.

Next page