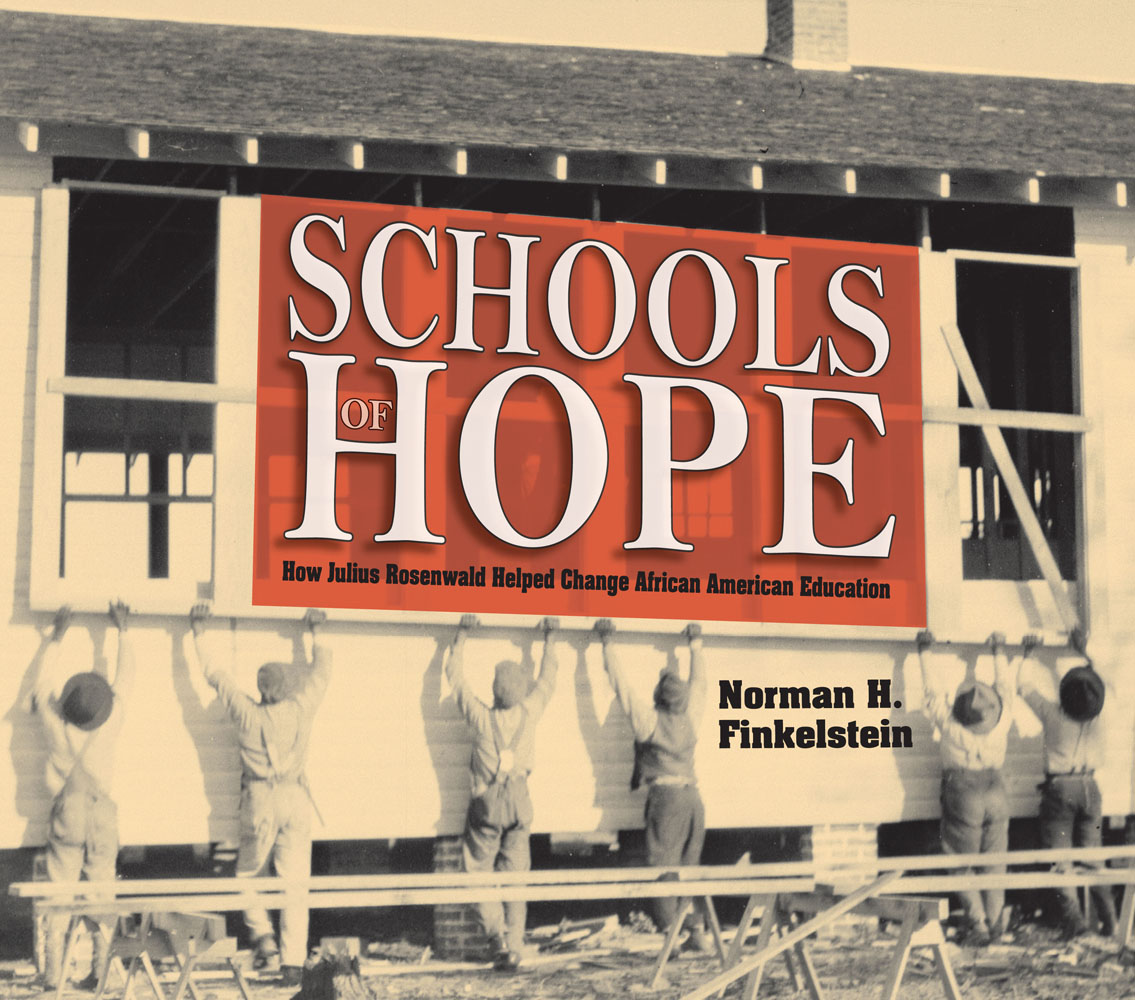

Built in 1923, the new Gloucester County Training School in Virginia (above), with its bright classrooms, replaced the old school (left) that was in poor condition.

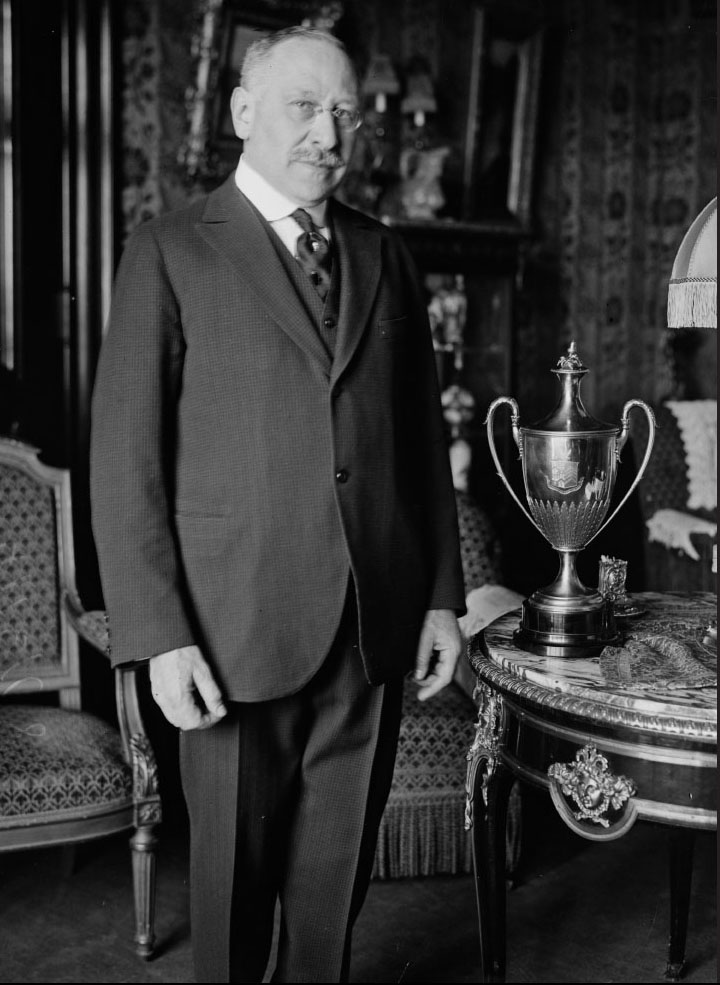

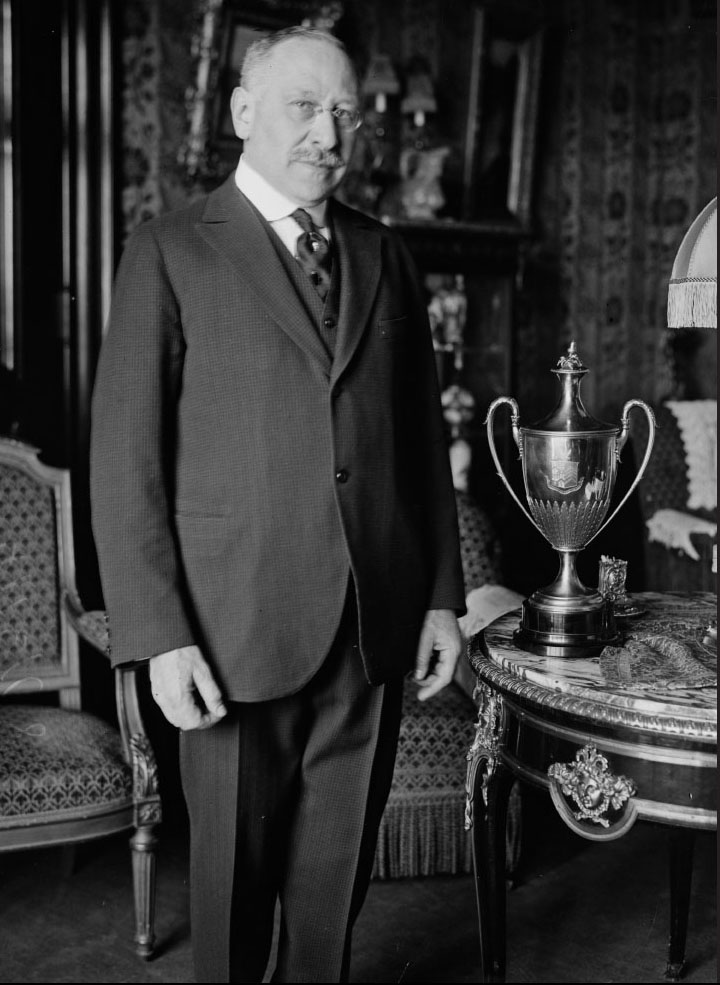

Julius Rosenwald established the fund that bore his name. Its greatest accomplishment was the building of more than 5,300 schools for African American children in the South during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Foreword

Julius Rosenwalds philosophy

M y grandfather was Julius Rosenwald, and he was a truly remarkable man. Unfortunately, I never knew him. He died ten years before I was born. But I researched and wrote his biography and discovered the grandfather I never knew.

In the early 1900s, under his leadership, Sears, Roebuck and Company became the largest retail establishment in the world. Rosenwalds office door was always open, and any employee could come to see him. According to a 1917 Forbes magazine article, Rosenwald was leaving the huge Sears, Roebuck plant on the West Side of Chicago one day with a friend. It was quitting time, and thousands of employees were on their way home. The friend turned to the Sears president and asked, How does it feel, Mr. Rosenwald, to have so many people working for you? Why, I never think of it in that way, he replied. I always think of them as just working with me.

Because of the success of Sears, Roebuck, Julius Rosenwald became a wealthy man. From a relatively young age, he had started giving money to charitable causes. At first, he contributed money mostly to Jewish causes, but he soon branched out. In 1917, Rosenwald established his own foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which became one of the largest foundations of its day. Yet Rosenwald also imposed a novel restriction on the fund: he wanted the foundation to spend itself out of existence after his death. He believed that foundations that lasted forever made no sense because one could not predict what issues would be important five hundred years in the future. Moreover, he strongly believed that each generation should give money to the causes that it believed in. Rosenwald tried to interest some of his wealthy contemporaries to follow his example, but none were very interested.

Perhaps in no way was Julius Rosenwald more ahead of his time than in the matter of race. After meeting Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald became increasingly convinced that blacks and whites were equal and should be treated as such. As this book makes clear, Julius Rosenwalds most enduring legacy was the establishment of quality schools for African Americans. More than 5,300 were built in fifteen Southern states, and they lasted until the civil rights era. A recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago indicates that the schools had a significant impact on raising the educational level of the students who attended them. The schools helped create a new black middle class in the South. Rosenwald had hoped that if blacks and whites within the same community worked together to raise funds for and build a school for blacks, it would break down racial barriers. This did not happen until the civil rights movement advanced in the 1960s, and even then it took many years to erode the prejudices of centuries. But building the schools was an important step on this road to equality.

Peter M. Ascoli, PhD

Chicago, Illinois

For the well-being of mankind

Rosenwald Fund By-Laws

The legacy of the Rosenwald schools continues today. Decades after the last school was built, people remember and honor the positive impact those schools had on their families. Throughout the South, community members are lovingly saving and restoring many of the remaining Rosenwald school buildings. This former Rosenwald school in Sumner County, Tennessee, was dedicated as a community center, with the assistance of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Lowes home improvement centers.

Marian Anderson sings before seventy-five thousand people at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., April 9, 1939.

REALIZING THE DREAM

The Rosenwald Fund... came to the aid of Negroes at that time.

Henry Allen Bullock, historian

O n Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, millions of Americans made themselves comfortable in front of their living room radios. Another seventy-five thousand people, including members of the United States Congress and the Supreme Court, settled into their seats at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. They were prepared to enjoy a special concert by Marian Anderson, one of the countrys most acclaimed concert singers. The original site for the concert was supposed to be Constitution Hall close by. But at nearly the last moment, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) denied Ms. Anderson the use of their hall. It seems they had overlooked a clause in the contract that prohibited the halls use by African Americans, like Marian Anderson.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt protested the DARs decision loudly. She not only resigned from the organization but also arranged the move to the Lincoln Memorial. When I stood up to sing our national anthem, Ms. Anderson later recalled, I felt for a moment as though I were choking. For a desperate second I thought that the words would not come.

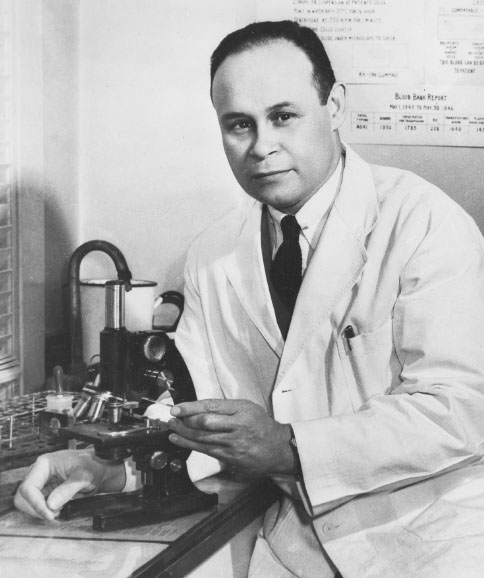

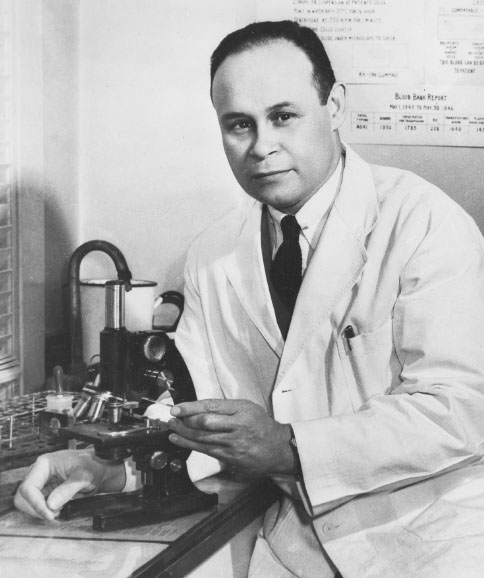

Dr. Charles Drew, the father of the blood bank, conducted groundbreaking research in storing and processing blood. His Rosenwald Fellowship allowed him to advance his education.