FROM

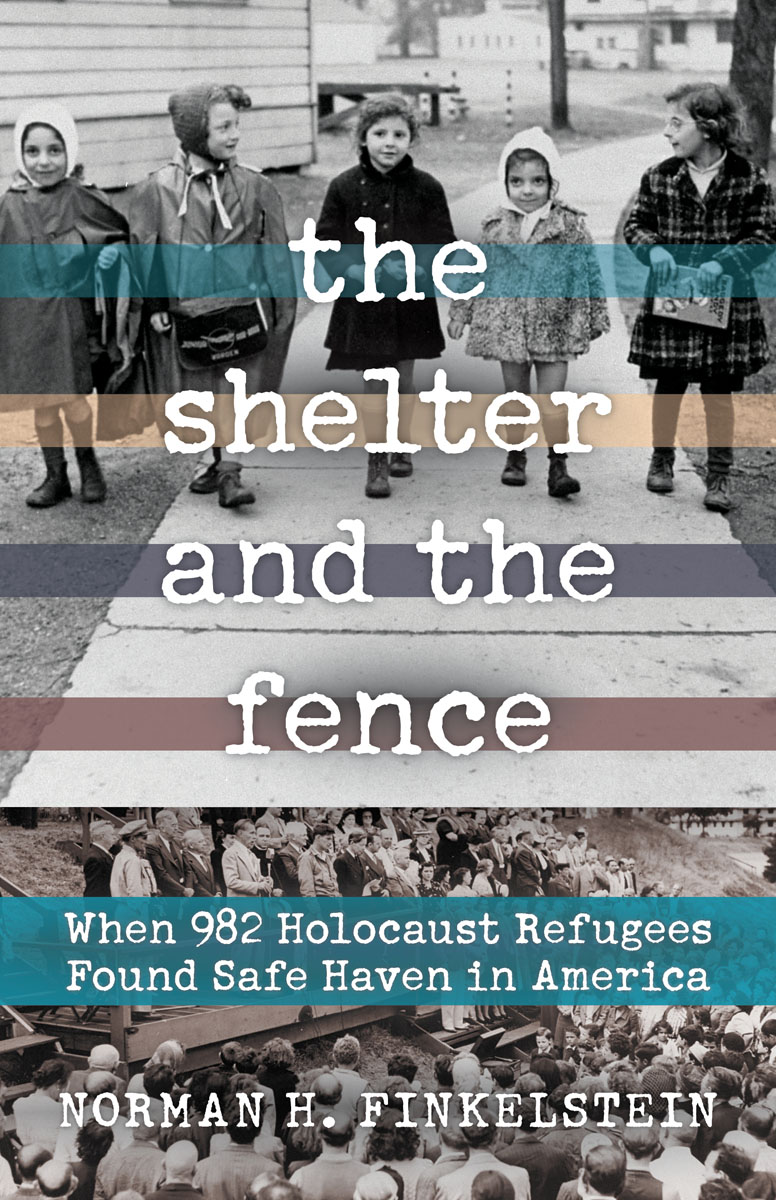

the shelter and the fence

T heir arrival at Fort Ontario resulted in another moment of panic. Although the morning was bright and sunny and the view of a shimmering blue Lake Ontario comforting, the sight of a barbed wiretopped fence encircling the shelter, guard watchtowers, and armed soldiers reminded them again of the life they left behind. The fear quickly disappeared as the refugees were welcomed with cookies and ice cream. One woman recalled, We had all this food, so we knew it wasnt a concentration camp.

While the adult refugees were being interviewed and fingerprinted, children felt free to explore the fort and approach the fence, where local Oswego residents gathered to watch the arrival. Local children and refugee children who couldnt speak each others languages soon found a way to communicate. One local little girl, Susan Saunders, passed her doll through the fence as a gift to a refugee girl. When the refugee children spotted Geraldine Rossiter arriving at the fence on her bicycle, they used their hands to indicate they too would like to ride. Without hesitation, she, with the help of onlookers, passed the bike over the barbed wire fence. For the refugee children, this was the first sign that they were about to enjoy the childhood that had been missing from their young lives.

Copyright 2021 by Norman H. Finkelstein

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-64160-383-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021933622

Interior design: Sarah Olson

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Rosalind

contents

1

the arrival

I cannot tell you how much we owe the United States for giving us this home.

Chaim Fuchs

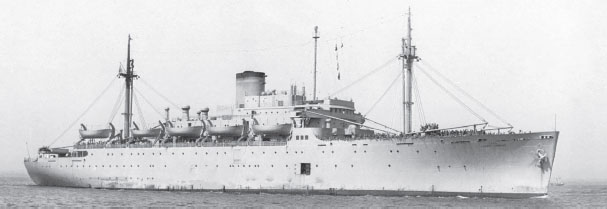

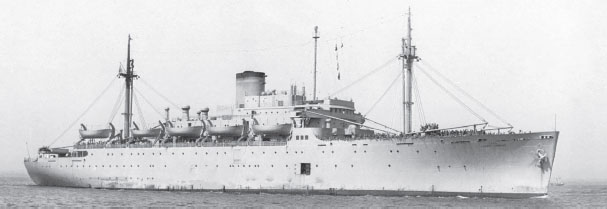

A t 7:30 AM on August 5, 2019, the church bells of Oswego, New York, rang out in unison. They marked the arrival at that exact time, seventy-five years earlier in 1944, of the first of two special trains to Fort Ontario. On board were 982 men, women, and children: refugees from Nazi terror in Europe, where World War II was still raging. Their 13-day journey began on July 20, when they boarded a US Army transport ship, the USAT Henry Gibbins, in the harbor of Naples, Italy. With German submarines and planes on the prowl in the Atlantic, the ship was part of a convoy of cargo and transport ships guarded by US Navy warships. It was not an easy voyage: there was constant fear of enemy attack, and along with the refugees, the ships decks were crowded with over 1,000 wounded American soldiers.

The USAT Henry Gibbins was used to transport wounded American soldiers as well as the 982 refugees. It had special safety features, including an elaborate fire-detecting apparatus and a unique sprinkler system in case of a shipboard fire.

The refugees represented 18 different nationalities, with 100 of them having survived Nazi concentration camps and 231 still under the age of 21. The oldest was over 80 years of age; the youngest was a three-day-old baby named Harry Maurer. His parents were Austrian, and he was born on a US Army transport truck on the way to the ship with the help of a British doctor. For the rest of his life he was affectionally known as International Harry. Of the 982 refugees, 874 were Jewish. The rest were of differing Christian denominations. What they all had in common was a will to live.

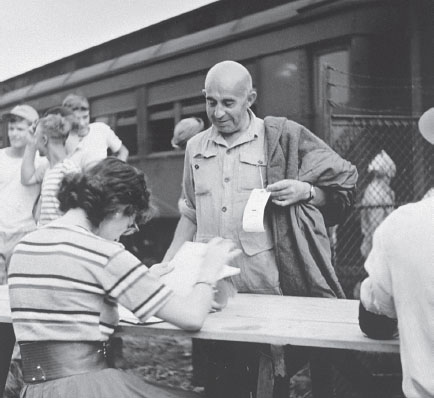

The harrowing sea journey ended on the evening of August 3, when the Henry Gibbins sailed into New York Harbor and passed the Statue of Liberty. The refugees welcome to America was not warm and personal but instead strictly governed by army regulations. The next morning, the refugees were taken off the ship, lined up for delousing with the insecticide DDT, which was sprayed on each of them by soldiers. Once their threadbare clothes were also disinfected, they were interviewed by American intelligence agents. Each refugee wore a hastily obtained cardboard identification tag: instead of a name, there was an identifying number. Further depersonalizing the arrivals, the tag carried the label U.S. A RMY C ASUAL B AGGAGE .

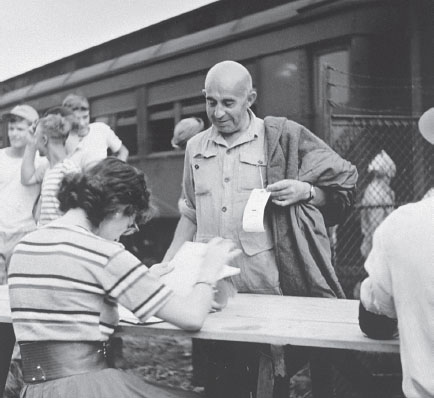

Refugees being checked in at the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter by representatives of the War Relocation Authority and the US Army.

Soldiers and Red Cross volunteers who helped the refugees off the ship were appalled by what they saw. The arrivals looked haggard, unshaven and generally unkempt. Their clothing was frayed and soiled. The most noticeable lack was that of shoes. A large number of the children were barefoot. Most were thin and frail. All were near exhaustion after their long ordeal. A crowd of relatives and friends, who learned about their arrival in the newspapers, was there to greet them. Because of the tight security they could only catch a glimpse from afar as police held them back. One of the volunteers observed, Some of the families here are decimated. They lost mother, father, six, seven, eight and nine brothers, in-laws, niecesall of them were deported and murdered in gas chambers. This group has suffered more than any I know of. The August 21 issue of Life magazine featured an article about their arrival at Fort Ontario, including numerous photographs of the refugees and their heroic stories of survival.

Refugee going through customs inspection. The card around her neck was her only identification.

Conditions improved as the refugees boarded ferries that took them across the Hudson River to Hoboken, New Jersey. The ferries were stocked with drinks and candy bars, and an army band played in the background. Some of the refugees were frightened at first when they saw the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad trains that would take them to Fort Ontario. Trains in Europe were often used to transport people to concentration camps. They soon realized that these trains were different. They would sit as passengers in the comfortable coach cars, and a hospital car was attached to carry the sick.

Their arrival at Fort Ontario resulted in another moment of panic. Although the morning was bright and sunny and the view of a shimmering blue Lake Ontario comforting, the sight of a barbed wiretopped fence encircling the shelter, guard watchtowers, and armed soldiers reminded them again of the life they had left behind. The fear quickly disappeared as the refugees were welcomed with cookies and ice cream. One woman recalled, We had all this food, so we knew it wasnt a concentration camp.

1

1