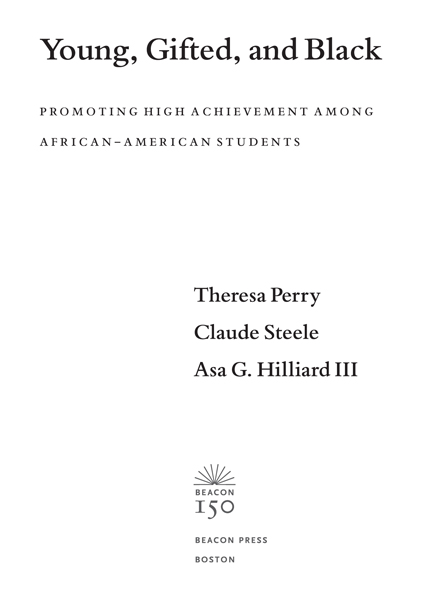

Theresa Perry - Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students

Here you can read online Theresa Perry - Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

An important and powerful book that radically reframes the debates swirling around the academic achievement of African-American students (Boston Review)

In three separate but allied essays, African-American scholars Theresa Perry, Claude Steele, and Asa Hilliard examine the alleged achievement gap between Black and white students. Each author addresses how the unique social and cultural position Black students occupyin a society which often devalues and stereotypes African-American identityfundamentally shapes students experience of school and sets up unique obstacles. Young, Gifted and Black provides an understanding of how these forces work, opening the door to practical, powerful methods for promoting high achievement at all levels.

In the first piece, Theresa Perry argues that the dilemmas African-American students face are rooted in the experience of race and ethnicity in America, making the task of achievement distinctive and difficult. She uncovers a rich, powerful African-American philosophy of education by reading African-American narratives from Frederick Douglass to Maya Angelou and carefully critiques the most popular theoretical explanations for group differences in achievement. She goes on to lay out how todays educators can draw from these sources to reorganize the school experience of African-American students.

Claude Steele follows up with stunningly clear empirical psychological evidence that when Black students believe they are being judged as members of a stereotyped grouprather than as individualsthey do worse on tests. He analyzes the subtle psychology of this stereotype threat and reflects on the broad implications of his research for education, suggesting scientifically proven techniques that teachers, mentors, and schools can use to counter the powerful effect of stereotype threat.

Finally, Asa Hilliards essay argues against a variety of false theories and misguided views of African-American achievement. She also shares examples of real schools, programs, and teachers around the country that allow African-American students to achieve at high levels, describing what they are like and what makes them work.

Now more than ever, Young, Gifted and Black is an eye-opening work that has the power to not only change how we talk and think about African-American student achievement but how we view the African-American experience as a whole.

Theresa Perry: author's other books

Who wrote Young, Gifted and Black: Promoting High Achievement among African-American Students? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.