Table of Contents

ALSO BY GEORGE SOROS

The Age of Fallibility:

The Consequences of the War on Terror (2006)

The Bubble of American Supremacy:

The Cost of Bushs War in Iraq (2003)

The Crisis of Global Capitalism:

Open Society Endangered (1998)

George Soros on Globalization (2001)

The New Paradigm for Financial Markets:

The Credit Crisis of 2008 and What It Means (2008)

Open Society: Reforming Global Capitalism (2000)

The Soros Lectures at the Central European University (2010)

Underwriting Democracy:

Encouraging Free Enterprise and Democratic Reform

Among the Soviets and in Eastern Europe (2004)

Introduction

by George Soros

Round Two of the Financial Crisis: Eurozone Meltdown and Its Super Bubble Roots

This series of essays published mainly in the Financial Times and the New York Review of Books constitutes a continuation of my previous books on the financial crisisThe New Paradigm for Financial Markets (2008) and The Crash of 2008 and What it Means (2009). It brings the story of the super bubble, which I contend started in 1980, up to date.

In 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president of the United States and Margaret Thatcher was prime minister of the United Kingdom, market fundamentalism became the dominant creed in the world. Market fundamentalists believe that financial markets would assure the optimum allocation of resources if only governments stopped interfering with them. They derive that belief from the efficient market hypothesis and the theory of rational expectations. These esoteric doctrines are based on certain assumptions which have little relevance to the real world, nevertheless they have become very influential. They dominate the economics departments of the leading American universities and from there, their influence has spread far and wide. In the 1980s they came to guide the policies of the United States and the United Kingdom. These countries embarked on deregulating and globalizing financial markets. That initiative spread like a virus. Individual countries have found it difficult to resist it because globalization allows financial capital to escape regulation and taxation and individual countries cannot do without financial capital.

Unfortunately the basic tenet of market fundamentalism is plain wrong: financial markets, left to their own devices, do not necessarily tend toward equilibriumthey are just as prone to produce bubbles. History shows that ever since financial markets came into existence they have always generated financial crises. Every crisis provoked a response from the authorities. That is how financial markets developed, hand in hand with central banking and market regulation.

When I started my career in finance, banks and currencies were strictly regulated. That was the legacy of the Great Depression and the Second World War. When the global economy became normalized under the Bretton Woods regime, financial markets started to revive. But financial markets, far from tending to equilibrium, generated imbalances which led to the gradual abandonment of the Bretton Woods regime.

The financial authorities function even less perfectly than markets. In the 1970s the Keynesian policies that had been inspired by the Great Depression allowed inflation to develop. Two successive oil shocks resulted in large surpluses for oil-producing countries and large deficits for oil importers. The imbalances between them were mediated by commercial banks. That is when the banks started to escape from the straight jacket they had been confined in by regulation.

Whenever the financial system ran into serious problems, the authorities intervened. They liquidated failing institutions or merged them into larger ones. The first systemically important disturbance occurred in the United Kingdom in 1973 when unregulated fringe banks like Slater Walker endangered the clearing banks financing them. The Bank of England intervened in the fringe banks in order to protect the clearing banks although the fringe banks were outside their normal sphere of competence. This set a pattern that was later followed during the super bubble: when the system is endangered the normal rules are suspended. This phenomenon was given a namemoral hazard.

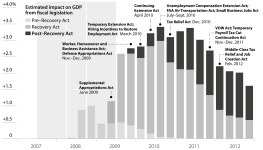

Bubbles are characterized by the unsound extension of credit and leverage. The intervention of the authorities created the super bubble by preventing ordinary bubbles from running their normal course. The authorities took care of failing institutions and if the economy was in danger they increased the money supply or applied fiscal stimulus.

The first international banking crisis of the super bubble occurred in 1982 when the credit extended to sovereign countries in the inflationary period of the 1970s became unsustainable and collapsed. The international monetary authorities banded together, used their clout to persuade the banks to roll over their loans, and lent enough money to the failing countries to pay the interest. The banking system was saved and the heavily indebted countries were subjected to severe discipline. Eventually the banks built up sufficient reserves to be able to write down the accumulated debt to manageable levels. At that point so-called Brady bonds were introduced to achieve orderly debt reorganizations. Latin American and other debtor countries lost a decade of growth in the process.

A number of localized financial crises were similarly containedthe Savings and Loan scandal of the mid-1980s was the most memorable of these. The next major international crisis began in 1997. It started in Asia where a number of countries tied their currencies to the dollar and used borrowings denominated in dollars to finance domestic growth. Eventually the accumulation of external deficits made the dollar pegs unsustainable and when the peg broke, many of the loans became delinquent. Again, the International Monetary Fund protected the banks and subjected the debtor countries to severe discipline. From Asia, the crisis spread to other parts of the world. In Russia, a default could not be avoided. This in turn exposed the vulnerability of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), an extremely highly-leveraged hedge fund employing highly-sophisticated risk management techniques based on the efficient market hypothesis. This posed a real threat to the global financial system because most of the largest banks were involved both in lending to LTCM and in holding the same positions for their own account. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York brought representatives of the major banks together in the same room and persuaded them to bail out LTCM. A meltdown was prevented and the super bubble continued to grow.

The next major episode was the high-tech bubble which burst in 2000. It was different from the other bubbles because it was fueled by the overvaluation of stocks rather than the unsound expansion of credit and leverage. Nevertheless, when the bubble burst the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates, eventually down to 1 percent, in order to prevent a recession. Alan Greenspan kept interest rates too low, too long. This gave rise to a housing boom which peaked in 2006, caused a financial crisis in August 2007, and terminated in the crash of October 2008.